5G judged safe by scientists but faces tougher radiation rules

- Published

5G phones are to be subject to tougher radiation limits.

But the standards body behind the new rules says there is no evidence that mobile networks cause cancer or other illnesses.

It has spent several years reviewing scientific literature on the effects of exposure to electromagnetic fields.

It says the new guidelines will provide improved protection for forthcoming 5G technologies that use high frequencies.

It is the first time since 1998 that the guidelines on protecting humans from radiation from phone networks, wi-fi and Bluetooth have been updated.

High frequencies

The rules do not impose new limits on 5G phone masts, but rather concern the phones themselves.

They impose what are described as "more conservative limits" on radiation from handsets when they connect to higher-frequency 5G networks.

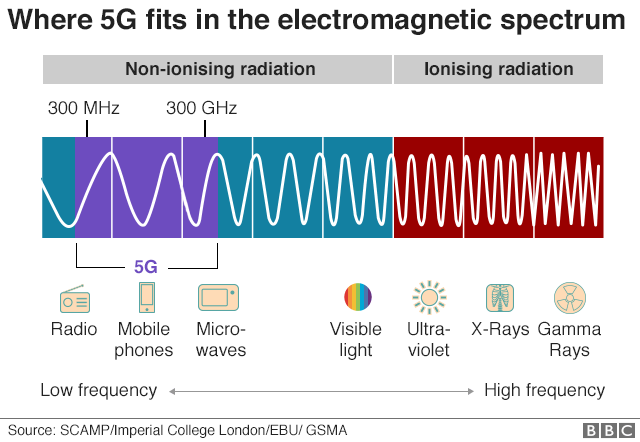

The changes focus on frequencies above 6 GHz. These are not used for 5G in the UK at the moment but could be in the future.

The benefit is that they can deliver very high speeds, but only over short distances.

The rules provide a "slightly higher level of protection than the current guidelines," the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP)'s chairman Dr Eric van Rongen told the BBC.

Mobile trade group GSMA said current 5G phones would not be affected as they already fall within the new standards' limits.

And industry insiders say new handsets are already being designed with the tighter guidelines in mind.

Scientific evidence

It concluded that apart from some heating of human body tissue, there was no evidence of harm.

"We also considered all other types of effects for instance, whether radio waves could lead to the development of cancer in the human body," said Mr van Rongen.

"We find that the scientific evidence for that is not enough to conclude that indeed there is such an effect."

The GSMA welcomed the announcement.

"Twenty years of research should reassure people there are no established health risks from their mobile devices or 5G antennas," said its chief regulatory officer John Giusti.

A number of campaign groups have been lobbying for even tighter rules, claiming that the higher frequencies used for 5G are dangerous.

"We know parts of the community are concerned about the safety of 5G, and we hope the updated guidelines will help put people at ease," said Mr van Rongen.

In the UK, the telecoms regulator Ofcom has been testing 5G mast sites to check that emissions do not exceed existing guidelines.

It has carried out 16 tests so far at sites where mobile use is high.

In each case, it found that radiation emissions were "a small fraction" of what was allowed, with the highest reading just 1.5% of the maximum level permitted.