Tech Tent: Hand over your virus data

- Published

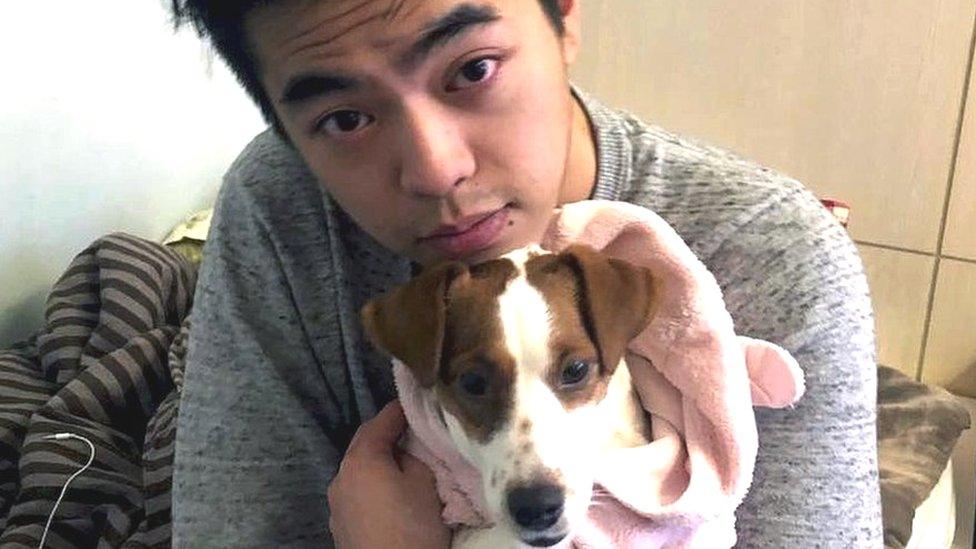

Milo Ho-Hsuan Hsieh was tracked after being put in quarantine with unexpected consequences

How much data are we all prepared to share in the battle to beat the coronavirus?

That is the theme of this week's Tech Tent which comes from my attic and the homes of contributors around the world.

Among them, a young Taiwanese journalist Milo Ho-Hsuan Hsieh. He came home to Taipei after a trip to Europe and was put into quarantine for 14 days and told that his phone would be satellite tracked.

Then one morning his phone ran out of battery and 45 minutes later the police came knocking at his door. They wanted to check that he was still at home, not evading quarantine.

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen live every Friday at 14:00 GMT on the BBC World Service

His story provoked horrified responses from some British readers who felt it showed a nightmarish vision of the powers of a police state.

But on Tech Tent, Milo reflects on what the incident shows about his own country's views on what powers the authorities should have during an emergency: "I think people are still pretty OK with restrictions to personal freedom because they see it as necessary to contain the spread of virus in Taiwan. I think when it comes to times of difficulty, people still kind of fall back on expecting the government to take all measures."

He says Taiwanese people also have at the back of their minds the Sars epidemic, where China was slow in releasing data about the disease and the country felt it did not act quickly enough. "Taiwan is shaped by that experience. It's been a lot more lenient on giving the government the power to do anything."

In the UK, there is talk of the National Health Service creating an app which would monitor the spread of the virus but some data experts are urging caution.

One symptom tracker app from the UK's King's College and health start-up Zoe quickly got 750,000 downloads

"There are so many different ways in which contact-tracking can be done, how it can be designed," Jeni Tennison of the Open Data Institute tells the programme. "And currently, there's very little transparency about what kind of design is being considered and implemented by the government."

But she says there are examples out there of good practice. She cites Singapore, which she says generally has a reputation for excessive surveillance of its citizens, but has developed an app which captures the bare minimum of data.

"So every time that you meet somebody with your phone, and they have the same app on their phone, it records the fact that you have met, but it doesn't record anything about where you are or who those other people are. It's only there so that if you catch the disease, those people that you have come into contact with or been close to you can get notified about that fact."

- Published28 February 2020

- Published24 March 2020