Is the UK's NHS Covid-19 app too private?

- Published

Cases are rising but is the app really able to help bring them down?

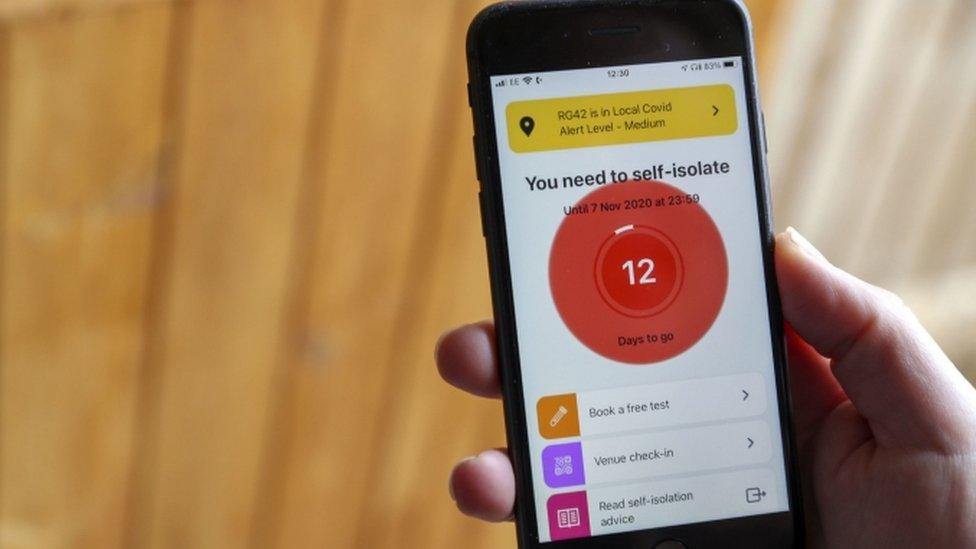

A major update to the NHS Covid-19 app should mean that it is better at identifying people who have been in contact with someone infected with the virus.

It should also send out more alerts telling those people to go into isolation.

But the way the app is designed using a privacy-focused toolkit provided by Apple and Google means it will be very difficult to know what effect it is having.

That's led some to suggest we've got the balance between privacy and effectiveness wrong.

It is clear that the team behind the NHS app can get only limited data about its effectiveness. They will have details of how many positive tests have been registered and how many alerts have been sent to users telling them to self-isolate - but not their identity or where and by whom they may have been infected.

"I feel sorry for them - they're flying blind," says Tom Loosemore, who helped found the Government Digital Service.

He says they are being denied the "meat and drink of contact tracing", information such as when people were infected and how to contact them by phone.

An update to the app means it will send more self-isolation alerts

Mr Loosemore has been a critic of the way governments around the world have allowed Apple and Google to, in effect, decide health policy by determining how their contact-tracing apps should work.

In the summer, the first version of the NHS app, which collected more data centrally was abandoned, partly because it was failing to identify contacts between some Apple iPhones. The second version, launched in England and Wales in late September, was built on the decentralised model designed by Apple and Google.

The UK switched to the Apple/Google model but does it mean that tech firms are deciding health policy?

That comes with strict limits on how much data can be extracted - for instance, it forbids apps from tracking a user's location.

But Michael Veale, a University College London academic who was involved in proposing a decentralised model even before Apple and Google came up with their system, says the NHS app team has gone even further than needed in protecting privacy: "Some of the design choices that the NHS Covid app made were more conservative than the Apple Google API is."

He says, for example, that users could have been asked when installing the app whether they would provide a phone number so that they could be called when they were being sent into isolation. "That's fine from a privacy point of view," he says. Instead, app users just see an alert - and can choose whether to obey it.

Ireland's contact-tracing app, which also uses the Apple Google toolkit, does ask users if they are willing to provide a phone number.

Then, if they get an exposure alert, they also get a call from the manual contact-tracing service with further advice. More than 80% of users have agreed to supply their number, which is stored on their phone rather than centrally and only supplied once the exposure notification has been triggered. The app's developers say this means they have a better idea of just how effective it is proving.

So why has the England and Wales app gone down a path which appears to limit its usefulness?

Mr Loosemore says he can understand the decisions made by the design team. He says there was a very effective privacy campaign in the late spring and early summer just as trust in the way the government was handling the pandemic was falling. "I have sympathy with the decisions that were made - I think the truth is that those decisions were made because trust got lost very early," he says.

Vietnam has been more effective in controlling the spread of Covid-19 but the crackdowns were tough

In recent days, some people have contrasted the measures used in the UK with the strategy used in places such as Taiwan or Vietnam which have been much more successful in controlling the virus.

Both Mr Loosemore and Mr Veale agree those are not useful comparisons. Taiwan and Vietnam had very effective manual tracing systems at an early stage, backed by more compulsion than we might be comfortable with here. Vietnam quarantined more than 200,000 people, many of them in hostels rather than at home, while Taiwan made sure people ordered into quarantine stayed at home by tracking their smartphones.

Mr Veale says using the NHS Covid-19 app to monitor whether people were obeying instructions to self-isolate would not work: "You have to ask yourself, if it was an enforcement system, would anyone download it at all?"

But Mr Loosemore thinks the focus back in the spring should have been on using the skills of NHS staff to build a proper manual contact-tracing system rather than being diverted by what he describes as a "fluffy app".

It has to be said that the team behind the NHS app do believe it is already doing an effective job in alerting people who may have been infected with the virus. But so far the Department of Health has been reluctant to reveal what data they have about its performance.

Update:

We asked the Department of Health why a feature allowing people who received an isolation alert to get a phone call had not been included in the app.

We did not receive an answer to that question but the department sent us this statement:

"The app has been designed with user privacy in mind, so it tracks the virus not people, and uses the latest in data security technology to protect privacy.

"The app will only notify users who are at risk if they have been near to an individual that has tested positive for Covid-19 and provides advice on what actions to take next."

- Published13 October 2020

- Published29 October 2020