DeepMind co-founder: Gaming inspired AI breakthrough

- Published

Demis Hassabis began his career as a video-games designer

Gaming inspired Demis Hassabis, the co-founder of DeepMind, to use artificial intelligence for a recent scientific breakthrough.

Predicting how a protein folds into a unique three-dimensional shape has puzzled scientists for half a century.

But London-based technology lab DeepMind has largely solved the problem, experts have announced.

The project, called Alpha Fold, is expected to accelerate research into a host of illnesses.

And the lab - owned by the same parent company as Google - has already used the system to help study the shape of proteins associated with the virus that causes Covid-19, external.

Dr Andriy Kryshtafovych, from the University of California, who has scrutinised the project, has described the achievement as "truly remarkable".

"Being able to investigate the shape of proteins quickly and accurately has the potential to revolutionise life sciences," he said.

DeepMind co-founder Demis Hassabis says gaming inspired his scientific work

Mr Hassabis spoke to Nick Robinson on BBC Radio 4's Today programme about the initiative:

Proteins are essential to almost every function in your body. And they're essential to all organisms. And the function of a protein depends on its 3D shape.

And there's been a long-standing more than 50-year-old grand challenge in science, which is can you go from the amino acid sequence - which is like a genetic sequence of letters that describes a protein - can you just from that one-dimensional letter sequence come up with a 3D structure?

People speculated, very famously, in the 1970s, and earlier than that, that it should be possible to do that, in theory. And ever since then, for the last five decades, people have been trying to write programs and computational methods that would allow them to directly go from the sequence to the 3D structure.

In essence, it's that problem that we solved with Alpha Fold now.

Before Alpha Fold cracked it, you'd watched human gamers trying to get to grips with it. And to some extent that inspired you, right?

That's right. I first came across it as an undergraduate, 20-plus years ago.

But then it came back on my radar in about 2009, where there was this game called Foldit, where some people had created a puzzle game out of proteins.

Gamers played it - and what they were doing was actually trying to turn the protein into a particular shape.

It turned out that through playing this game... they actually discovered a couple of very important structures for real proteins.

Firstly, it was a fascinating use of games in science - and games is another one of my interests.

But secondly, it kind of suggested to me that somehow these gamers had trained their intuition and their pattern-matching capabilities so that somehow they were able to do what brute-force computer systems couldn't at the time - and actually come up with the right shapes.

That made me think that AI could maybe try to mimic that intuitive capability that those gamers were demonstrating.

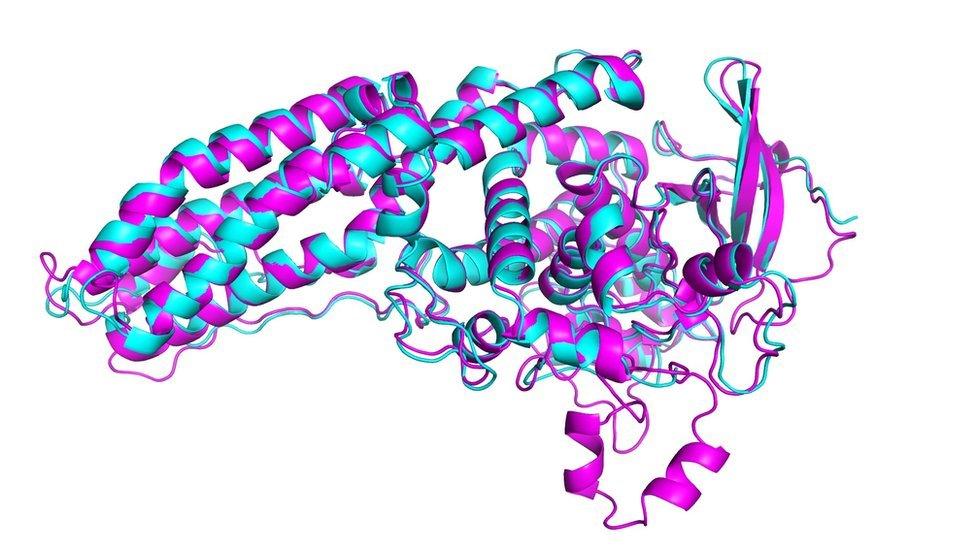

A DeepMind model of a protein from legionnaires' disease bacteria

What do you hope to be able to do now you're at the beginning, at least, of cracking these folding proteins?

The plan behind DeepMind was always to try to build artificial intelligence in a very general way - so, use inspiration from the way the brain works, I'd studied neuroscience as well as computer science, and try and fuse the ideas that we know from the brain and bring some of those ideas across into algorithms.

The plan for us and what we've been doing at DeepMind was to test those algorithmic ideas initially on games. What we've been best known for up until now is cracking games like Go and Atari.

But in the back of our minds, the ultimate goal in the end was not to win at games, even though that was impressive in terms of AI, it was to develop algorithms that could be applied to important real-world problems.

And what better problems to apply them to than important grand challenges in science? We hope by cracking those problems, say like protein folding, we unlock whole new opportunities and avenues for new exploration.

Now, you mentioned that you're a game enthusiast. That in many ways is where it began for you, isn't it? You were rather brilliant at chess as a child, went on to design games and DeepMind is where you ended up?

Games is what was my first passion, if you like, and it's also what got me into AI indirectly.

I started with playing chess for various England junior teams. And then, as part of that, we got a chess computer, very early on, that I used to train on.

I think that started sparking off in in my mind ideas about how does the chess computer play chess and learning about that.

I got fascinated with computers. And then the natural endeavour then was to go into AI and combine those passions together - computers with gaming - and then ending up, you know, designing and writing computer games.

People may love the idea of their children or grandchildren playing chess but get very edgy when they're looking at screens. What would you say to them?

I definitely think there's no harm in playing games.

I think it depends on doing it in moderation, like anything.

And I'd also say if you compare it to a lot of other leisure pursuits, say like watching TV or something like that, I think it's a lot more of an active endeavour than that.

It's a gateway. Many children start by playing games, like I did, and then getting into programming and then using this incredible tool, the computer, to create things.

Related topics

- Published30 November 2020

- Published18 September 2019

- Published11 July 2019

- Published3 July 2017