Online harms law to let regulator block apps in UK

- Published

The new law aims to protect children and adults using the internet

UK watchdog Ofcom is set to gain the power to block access to online services that fail to do enough to protect children and other users.

The regulator would also be able to fine Facebook and other tech giants billions of pounds, and require them to publish an audit of efforts to tackle posts that are harmful but not illegal.

The government is to include the measures in its Online Harms Bill.

The proposed law would not introduce criminal prosecutions, however.

Nor would it target online scams and other types of internet fraud.

This will disappoint campaigners, who had called for the inclusion of both.

It will, however, allow Ofcom to demand tech firms take action against child abuse imagery shared via encrypted messages, even if the apps in question are designed to stop their makers from being able to peer within.

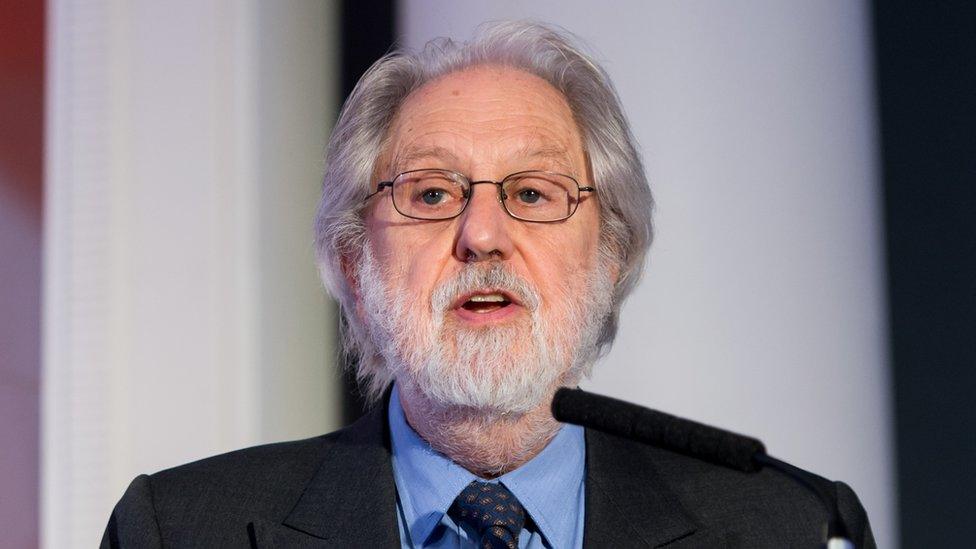

Secretary of State Oliver Dowden laid out his vision for the bill in parliament

Digital Secretary Oliver Dowden told parliament the legislation represented "decisive action" to protect both children and adults online.

"A 13-year-old should no longer be able to access pornographic images on Twitter, YouTube will not be allowed to recommend videos promoting terrorist ideologies and anti-Semitic hate crimes will need to be removed without delay."

And he said that the government would introduce secondary legislation to introduce criminal sanctions for senior managers", if those changes did not come about.

Mr Dowden made a commitment to bring the bill before parliament in 2021, but it might not be until 2022 or later before it comes into force.

The Children's Commissioner for England, Anne Longfield, said there were signs that new laws would have "teeth", including strong sanctions for companies found to be in breach of their duties.

She welcomed the requirement on messaging apps to use technology to identify child abuse and exploitation material when directed to by the regulator.

"However, much will rest on the detail behind these announcements, which we will be looking at closely," she added.

The TechUK trade association said "significant clarity" was needed about how the proposals would work in practice, adding that the "prospect of harsh sanctions" risked discouraging investment in the sector.

Will the new law tackle 'fake news' and conspiracy theories?

Alistair Coleman, BBC Monitoring

The Online Harms Bill concentrates its fire on the very real dangers posed by child sexual exploitation, terrorism, bullying and abuse, but also addresses "fake news" on social media.

There have been calls to tackle disinformation for years, especially after the issue was highlighted during the 2016 US presidential election and Brexit referendum campaigns.

This year alone, misleading content about Covid-19, vaccines and 5G mobile technology has resulted in real-life harm - mobile phone masts have been torched as a result of conspiracy theories, and some people around the world were convinced that Covid-19 posed no real threat, leading to illness and death.

The government's consultation says that social media companies' response to disinformation has been too patchy, exposing users to potentially dangerous content.

But the government itself has been criticised for what was described as "unacceptable" delays in publishing the Online Harms Bill, and now it's unlikely to come into effect before 2022. When it does, content that could cause harm to public health or safety will fall under Ofcom's powers.

With potentially harmful anti-vaccine posts spreading online, could both social media companies and the authorities have acted earlier?

Mega fines

The government claims the new rules will set "the global standard" for online safety.

Plans to introduce the law were spurred on by the death of 14-year-old Molly Russell, who killed herself after viewing online images of self-harm.

In 2019, her father Ian Russell accused Instagram of being partly to blame, leading ministers to demand social media companies take more responsibility for harmful online content.

"For 15 years or so, the platforms have been self-regulating and that patently hasn't worked because harmful content is all too easy to find," he told BBC Radio Four's Today programme.

He added that unless top executives could be held criminally liable for their products' actions then he did not believe they would change their behaviour.

In his parliamentary statement, Mr Dowden said he has asked the Law Commission "to examine how the criminal law will address" this sensitive area.

"We do need to take careful steps to make sure we don't inadvertently punish vulnerable people, but we do need to act now to prevent future tragedies," he said.

The death of Molly Russell prompted calls for tougher rules to be imposed on online services used by teenagers

Under the proposals, Ofcom would be able to fine companies up to 10% of their annual global turnover or £18m - whichever is greater - if they refused to remove illegal content and/or potentially failed to satisfy its concerns about posts that were legal but still harmful.

Examples of the latter might include pornography that is visible to youngsters, bullying and dangerous disinformation, such as misleading claims about the safety of vaccinations.

In addition, Ofcom could compel internet service providers to block devices from connecting to offending services.

The regulator would be given ultimate say over where to draw the line and what offences would warrant its toughest sanctions.

But in theory, it could fine Instagram's parent company Facebook $7.1bn and YouTube's owner Google $16.1bn based on their most recent earnings.

The new regulations would apply to any company hosting user-generated content accessible to UK viewers, with certain exceptions including news publishers' comments sections and small business's product review slots.

So, chat apps, dating services, online marketplaces and even video games and search engines would all be covered.

However, the bigger companies would have added responsibilities. including having to publish regular transparency reports about steps taken to tackle online harms, and being required to clearly define what types of "legal but harmful" content they deem permissible.

In response, Facebook's head of UK public policy Rebecca Stimson said that it has "long called for new rules to set high standards", adding that regulations were needed "so that private companies aren't making so many important decisions alone".

'Clear and manageable'

The child protection charity NSPCC had wanted the law to go further by threatening criminal sanctions against senior managers.

While it is planned for the bill to mention the possibility, it would only be as a provision that would require further legislation.

"We set out six tests for robust regulation - including action to tackle both online sexual abuse and harmful content and a regulator with the power to investigate and hold tech firms to account with criminal and financial sanctions," said the NSPCC's chief executive Peter Wanless.

"We will now be closely scrutinising the proposals against those tests."

A spokesman for the government said ministers wanted to see how well the initial set of powers worked before pursuing criminal action.

MoneySavingExpert.com founder Martin Lewis and the Mental Health Policy Institute have also campaigned for the law to give the watchdog new powers, external to crack down on scammers.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But the government suggested that it made sense to keep the regulations "clear and manageable" by leaving this to other laws.

Well, it's taken a while. For at least the past four years, British and American governments have talked up their plans to regulate the data giants.

Way back in the distant era of April 2019, then Home Secretary Sajid Javid, and then Culture Secretary Jeremy Wright pledged tough new rules to reduce online harms - years after a White Paper was first mooted.

Brexit has taken up a lot of government bandwidth, of course. And then a pandemic did the same.

But there is another reason for the delay. Regulating technology is very hard.

Technology companies are global, exceptionally innovative, and spend huge sums on lobbying.

Regulation is national, slow, and complicated.

These new rules come just a fortnight after the announcement of a Digital Markets Unit to curb the monopolistic tendencies of Big Tech.

In both the economic and social sphere, a new compact between democracy and the data giants is - hesitantly - emerging.

Encrypted images

The government is keen, however, to avoid the law curtailing freedom of expression,

So, it has promised safeguards to ensure users can still engage in "robust debate".

The law would require WhatsApp to tackle child abuse imagery in encrypted chats

These would include requiring companies to let users appeal against any content takedowns.

Companies would also be told to consider what impact automated censorship systems might have when applied to chat apps or closed groups, where users expect to have more privacy.

But the law would also let Ofcom demand that firms monitor, identify and remove illegal child sexual abuse and exploitation materials wherever they appear.

And it could demand this of end-to-end encrypted chat apps including WhatsApp, Apple's iMessage and Google's Messages, even though their use of digital scrambling is intended to prevent the providers being able to monitor content.

A government spokesman said the intention was for this to be a "last resort" measure used to tackle "persistent offences" when alternative approaches had failed.

Even so, privacy campaigners are likely to push for further details about how this would be possible without compromising security.

Related topics

- Published15 December 2020

- Published8 December 2020

- Published29 June 2020

- Published8 April 2019