Racial abuse: Is ending anonymity on social media the answer?

- Published

Marcus Rashford says he was subjected to "social media at its worst" after Manchester United's 0-0 draw with Arsenal

The social-media giants are in the dock again over their failure to police their platforms effectively.

This time it's the wave of racist abuse sent to Manchester United's Marcus Rashford and other Premier League footballers that has prompted calls for action.

From the Duke of Cambridge to the FA, the pressure is mounting on Twitter, Instagram and other platforms to do more to stop the hateful messages.

The companies are being urged to use their artificial-intelligence expertise to spot racist messages even as they are being written and either urge users to think again or prevent them from posting them.

But another idea apparently gaining traction is ending anonymity on social media, so the racists can be tracked down.

Verification information

Last December, Labour's Margaret Hodge, who says she receives thousands of abusive tweets every month, called for a ban on anonymity for social-media users to be part of the Online Harms Bill.

"People argue that anonymity allows proper democratic participation - but I think the harms outweigh the benefits," she told the Guardian, external.

Anti-racism campaigners are not saying everyone needs necessarily to post in their own name but rather give the social networks a means to identify them if they break the law.

"You need to have that verification information so that if someone abuses the privilege of anonymity, that information can be quickly and transparently shared with law enforcement and clubs," Kick It Out chief executive Sanjay Bhandari told BBC Radio 4's Today programme on Monday.

Avoiding harm

It sounds a simple and obvious solution.

But when I canvassed opinion about this approach on Twitter, many respondents - both named and anonymous - saw plenty of problems.

In some parts of the world, they pointed out, anonymity was vital for people wanting to express their feelings about their government - or talk about their sexuality.

And that was true at home as well as abroad, tech start-up Aplisay founder @robinjpickering said.

"Lets not kid ourselves that this only applies in places outside our borders," he wrote.

"Even here, openness about sexuality, publicly disagreeing with an employer, or escaping an abusing partner are all circumstances where privacy is needed to avoid harm."

Private lives

If anonymity was banned, a teacher tweeting as @curiousiguana said, "I'd basically have to leave".

"My feed isn't particularly out-there," the account holder wrote.

"But teachers cannot risk pupils finding their private lives.

"The line between professional and personal means I have to stay anonymous or go bland/apolitical/unfunny."

Swift removals

And social-science researcher Sunil Rodger, who tweets as @sunildvr, said: "This is not a 'technical' issue per se but a social issue.

"As such, a simplistic technical solution, such as banning anonymity, won't solve the social issues around it."

Others saw ways of limiting the use of anonymous accounts without abolishing them altogether.

"I accept there's a limited case," Damian Rafferty, who tweets as @mrfly, said.

"But what I would like to see is some serious work on making the lives of trolls and racists much harder - verification, no tweets for 14 days on new accounts, swift removals, et cetera."

'It's anarchy'

For some though, including former MP Helen Goodman - @helengoodmanBA - there is only one answer to ending the abuse.

"I've long been a believer in ending anonymity," she wrote.

"It's not liberty, it's anarchy."

And public-relations expert @ellaminty agrees.

'Words hurt'

"Words can kill," she wrote.

"Words hurt.

"Words can destabilise so much and affect so many.

"It's all about owning up.

"Social media is a market, not a protected space.

"For the latter, one has the dark net."

Curbing abuse

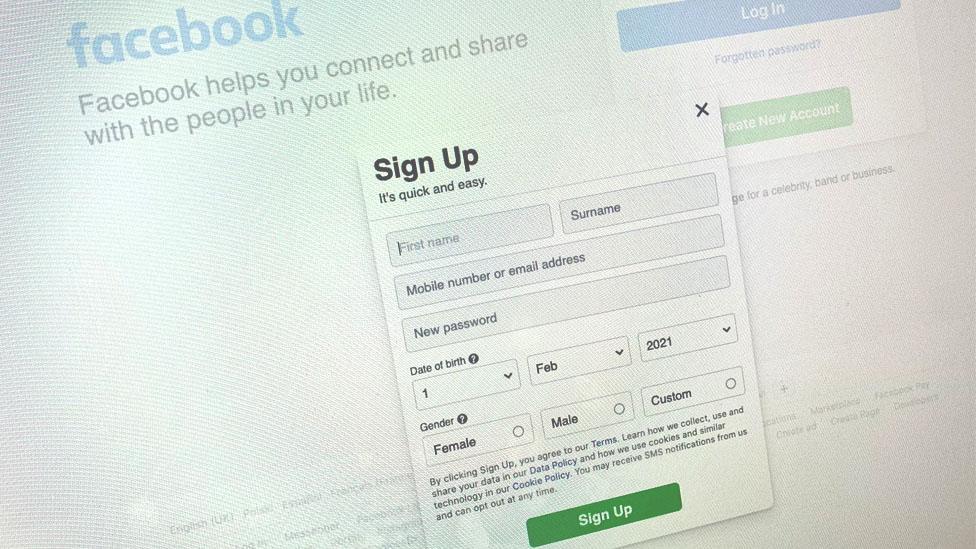

It is, however, worth remembering social networks that require people to use their real names are not immune from abuse.

Facebook has struggled to police the behaviour of its users .

And Parler, the network favoured by many banned from other social-media platforms, asked for photo ID when people opened accounts.

Facebook requires users to provide the "the name they use in real life" when they join, although not everyone complies

There may be some political pressure to include a ban on online anonymity in the long-awaited Online Harms Bill.

But it seems likely the government will see too many practical difficulties with that approach.

And that will increase the pressure on the platforms to find some other, technical way of curbing abuse.

- Attribution

- Published31 January 2021

- Attribution

- Published31 January 2021

- Published15 December 2020