Pegasus scandal: Are we all becoming unknowing spies?

- Published

The Israel-based NSO Group says its customers are carefully assessed

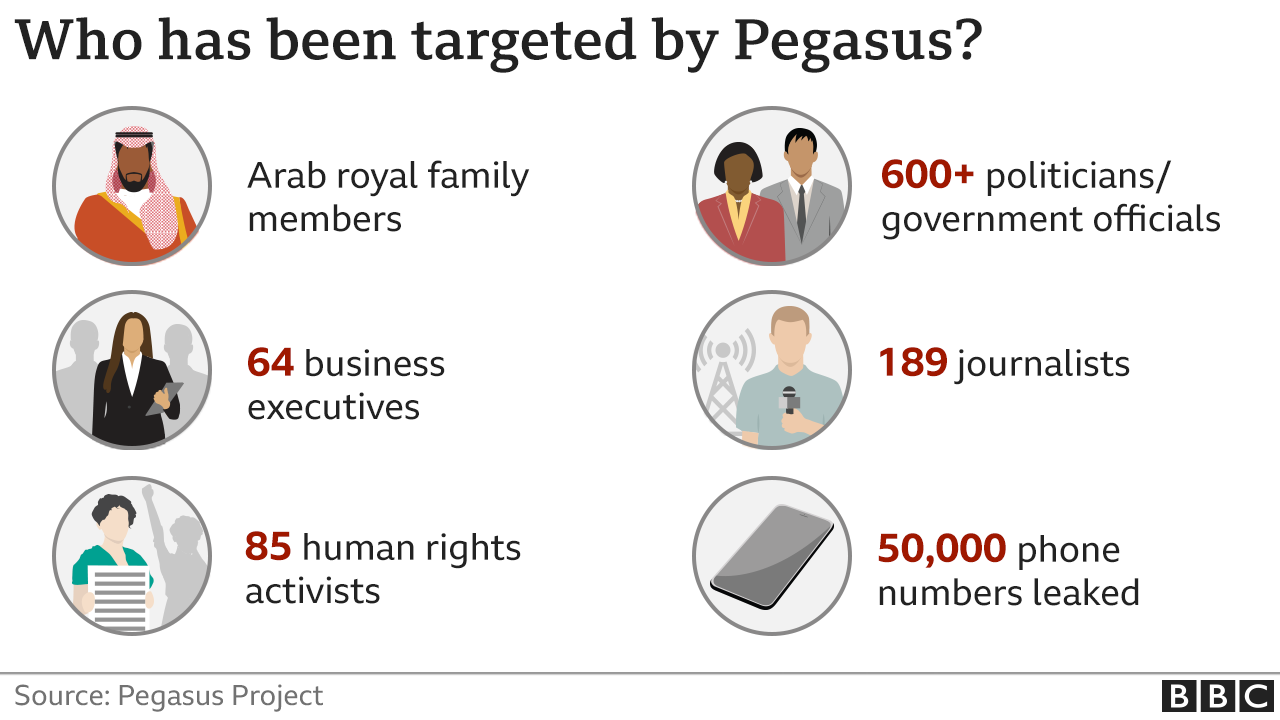

The allegations that spy software known as Pegasus may have been used to carry out surveillance on journalists, activists - and even perhaps political leaders - highlights that surveillance is now for sale.

The company behind the tool, NSO Group, has denied the allegations and says its customers are carefully assessed.

But it is another sign that high-end spy techniques, which used to be the exclusive preserve of a few states, are now spreading more widely and challenging the way we think about privacy and security in an online world.

In the not-too-distant past, if a security service wanted to find out what you were up to, it took a fair degree of effort. They might get a warrant to wiretap your phone. Or plant a bug in your house. Or send a surveillance team to follow you.

Finding out who your contacts were and how you lived your life would take patience and time.

Now, almost everything they might want to know - what you say, where you have been, who you meet, even what interests you - is all contained in a device we carry all the time.

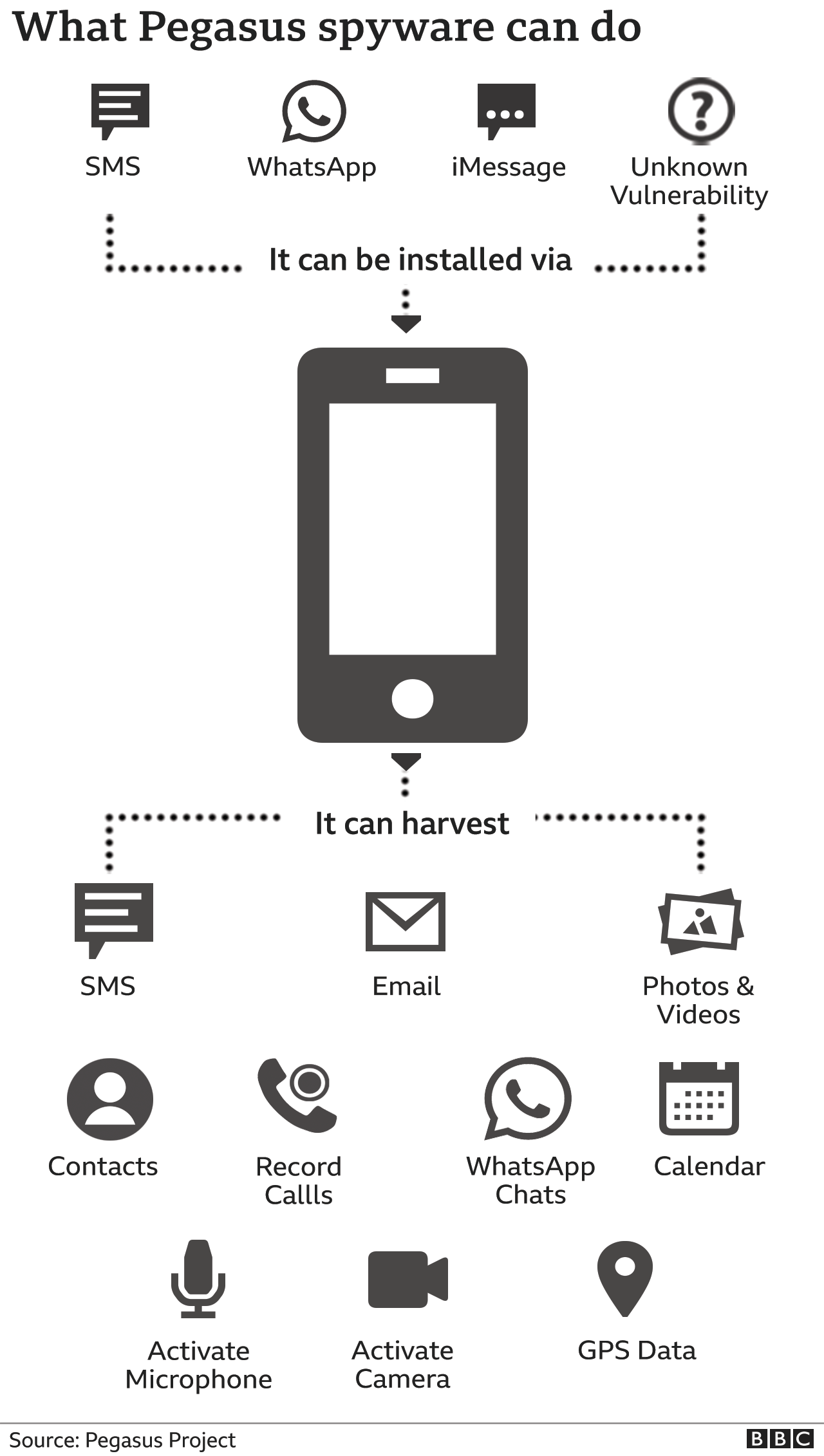

Your phone can be accessed remotely without anyone even touching it and you never knowing that it's been turned from your friendly digital assistant into someone else's spy.

The ability to remotely access that phone was once considered something only a few states could do. But high-end espionage and surveillance powers are now in the hands of many other countries and even individuals and small groups.

Former US intelligence contractor Edward Snowden revealed the power of US and UK intelligence agencies to tap into global communications in 2013.

Those agencies always maintained that their capabilities were subject to the authorisations and oversight of a democratic country. These authorisations were fairly weak at the time, but have since been strengthened.

His revelations, however, prompted other nations to consider what was possible. Many became eager for the same kinds of capabilities and a select group of companies - most of which have kept a low profile - have increasingly sought to sell it to them.

Israel has always been a first-tier cyber-power with top-end surveillance capabilities. And its companies, like NSO Group, often formed by veterans of the intelligence world, have been among those to commercialise the techniques.

NSO Group say they only sell their spyware for use against serious criminals and terrorists. But the problem is how you define those categories.

More authoritarian countries frequently claim journalists, dissidents and human rights activists are criminals or a national security threat making them worthy of intrusive surveillance.

And in many of those countries there is limited or no accountability and oversight on how the powerful capabilities are used.

The spread of encryption has increased the drive for governments to get inside people's devices. When phone calls were the main means of communication, a telecoms company could be ordered to wiretap the conversation (which once meant literally attaching wires to the line).

But now the conversations are often encrypted, meaning you need to get to the device itself to see what was said. And devices also carry out a much richer treasure trove of data.

States sometimes come up with clever ways of doing this. A recent example was a joint US-Australian operation in which criminal gangs were given phones they thought were super secure but were really operated by law enforcement.

But the issues are wider than this kind of phone spyware. Other high-end intelligence capabilities are also spreading fast.

Even the tools to disrupt a business online are now easily accessible.

In the past, ransomware - in which hackers demand a payment to unlock access to your system - was the province of criminal networks. It is now sold as as a service on the dark web.

An individual can simply agree a deal to give them a cut of the profits and they will hand over the tools and even offer support and advice, including helplines in the case of problems.

Other techniques - like location tracking and developing profiles of people's activity and behaviour - which once required specialised access and authority are now available freely.

And when it comes to surveillance, it is not just about states.

It is also about what companies can do to track us - not necessarily by implanting spyware, but through a surveillance economy in which they watch what we like on social media to better market us to companies.

All of this creates pools of data that companies can use - but which hackers can steal and states can seek to tap into.

Some capabilities are now on sale to everyone. Other types of spyware are for sale to the nervous or suspicious who want to check on their family's whereabouts.

What all of this means, then, is that we may be stepping into a world in which we can all become spies - but can equally all be spied on.

What’s it like to have spyware on your phone?

- Published19 July 2021

- Published30 October 2019

- Published31 October 2019

- Published25 October 2019

- Published25 October 2019