What the Online Safety Act is - and how to keep children safe online

- Published

The way people in the UK might navigate the internet is changing.

Under the Online Safety Act, platforms must take action - such as carrying out age checks - to stop children seeing illegal and harmful material from July.

Services face large fines if they fail to comply with UK's sweeping online safety rules. But what do they mean for children?

Here's what you need to know.

What is the Online Safety Act and how will it protect children?

The Online Safety Act's central aim is to make the internet safer for people in the UK, especially children.

It is a set of laws and duties that online platforms must follow, being implemented and enforced by Ofcom, the media regulator.

Under its Children's Codes, platforms must prevent young people from encountering harmful content relating to suicide, self-harm, eating disorders and pornography from 25 July.

This will see some services, notably porn sites, start checking the age of UK users.

Ofcom's rules are also designed to protect children from misogynistic, violent, hateful or abusive material, online bullying and dangerous challenges.

Firms which wish to continue operating in the UK must adopt measures including:

changing the algorithms which determine what is shown in children's feeds to filter out harmful content

implementing age verification methods to check whether a user is under 18

removing identified harmful material quickly and supporting children who have been exposed to it

identifying a named person who is "accountable for children's safety", and annually review how they are managing risk to children on their platforms

Failure to comply could result in businesses being fined £18m or 10% of their global revenues - whichever is higher - or their executives being jailed.

In very serious cases Ofcom says it can apply for a court order to prevent the site or app from being available in the UK.

What else is in the Online Safety Act?

The bill also requires firms to show they are committed to removing illegal content, including:

child sexual abuse

controlling or coercive behaviour

extreme sexual violence

promoting suicide or self-harm

selling illegal drugs or weapons

terrorism

The Act has also created new offences, such as:

cyber-flashing - sending unsolicited sexual imagery online

sharing "deepfake" pornography, where artificial intelligence is used to insert someone's likeness into pornographic content

Why has it been criticised?

A number of campaigners want to see even stricter rules for tech firms, and some want under-16s banned from social media completely.

Ian Russell, chairman of the Molly Rose Foundation - which was set up in memory of his daughter who took her own life aged 14 - said he was "dismayed by the lack of ambition" in Ofcom's codes.

The Duke and Duchess of Sussex have also called for stronger protection from the dangers of social media, saying "enough is not being done".

They unveiled a temporary memorial in New York City dedicated to children who have died due to the harms of the internet.

"We want to make sure that things are changed so that... no more kids are lost to social media," Prince Harry told BBC Breakfast.

The NSPCC children's charity argues that the law still doesn't provide enough protection around private messaging apps. It says that the end-to-end encrypted services which they offer "continue to pose an unacceptable, major risk to children".

On the other side, privacy campaigners complain the new rules threaten users' freedom.

Some also argue age verification methods are invasive without being effective enough.

Digital age checks can lead to "security breaches, privacy intrusion, errors, digital exclusion and censorship," according to Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch.

How much time do UK children spend online?

Children aged eight to 17 spend between two and five hours online per day, according to Ofcom research, external.

It found that nearly every child over 12 has a mobile phone and almost all of them watch videos on platforms such as YouTube or TikTok.

About half of children over 12 think being online is good for their mental health, according to Ofcom.

However, the Children's Commissioner said that half of the 13-year-olds her team surveyed reported seeing "hardcore, misogynistic" pornographic material on social media sites.

Children also said material about suicide self-harm and eating disorders was "prolific" and that violent content was "unavoidable".

What online parental controls are available?

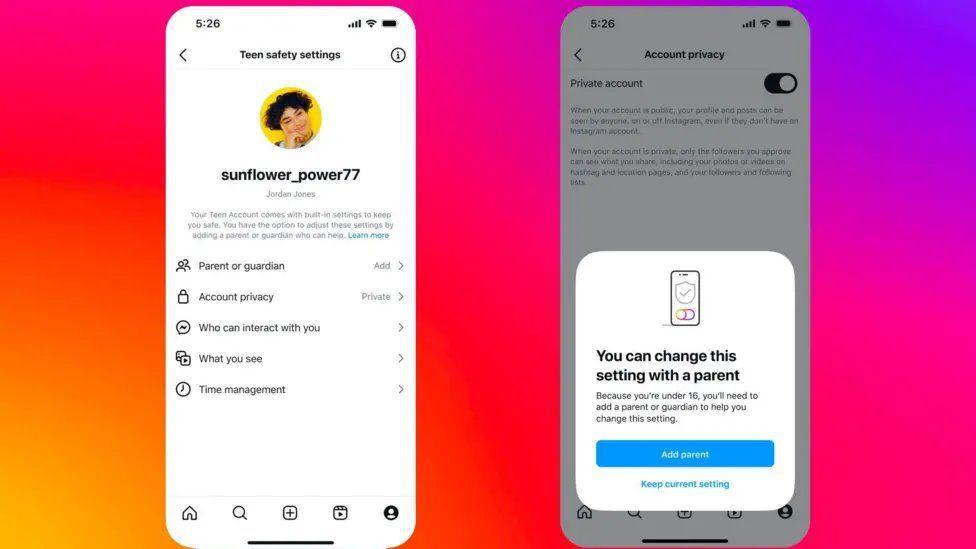

Instagram says it doesn't let 13 to 15-year-old users make their account public unless they add a parent or guardian to their Teen Account

The NSPCC says it's vital that parents talk to their children about internet safety, external and take an interest in what they do online.

Two-thirds of parents say they use controls to limit what their children see online, according to Internet Matters, a safety organisation set up by some of the big UK-based internet companies.

It has a list of parental controls available, external and step-by-step guides, external on how to use them.

These include advice on how to manage teen or child accounts on social media, video platforms such as YouTube, and gaming platforms such as Roblox or Fortnite.

However Ofcom data suggests that about one in five children are able to disable parental controls.

Instagram has already introduced "teen accounts" which turn on many privacy settings by default - although some researchers have claimed they were able to circumvent the promised protections.

What controls are there on mobile phones and gaming consoles?

Phone and broadband networks may block some explicit websites until a user has demonstrated they are over 18.

Some also have parental controls that can limit the websites children can visit on their phones.

Android, external and Apple, external devices also offer options for parents to block or limit access to specific apps, restrict explicit content, prevent purchases and monitor browsing.

Game console controls also let parents ensure age-appropriate gaming and control in-game purchases, external.

Parents can limit purchases and access to age-restricted games in Nintendo Switch consoles.

Sign up for our Tech Decoded newsletter to follow the world's top tech stories and trends. Outside the UK? Sign up here.