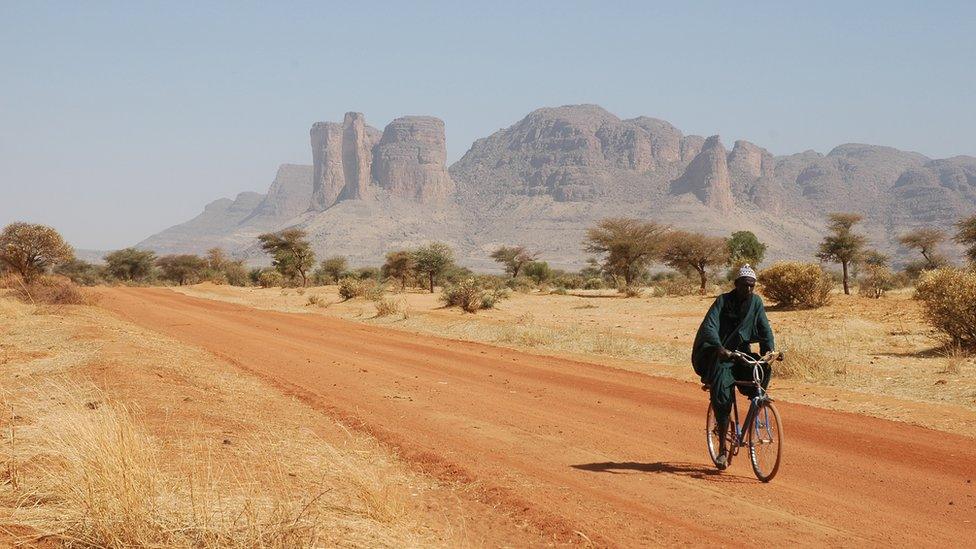

The battle on the frontline of climate change in Mali

- Published

Mali is lurching between drought and flood

Everything about Mami exudes exhaustion. Her round brown eyes are pools of sadness, and her bulbous body throbs with pain.

"First, armed groups attacked nearby," she explains in a tired voice as we sit on plastic matting, five young children nestled close to their mother in Mali's fabled city in the sand Timbuktu.

"Then the rains came, and did the rest."

The worst rains in 50 years in northern Mali washed away their entire crop.

Those rains poured through the cracks in her mud home caused by an explosion an armed group set off.

Mami lost her entire crop to the worst rains Mali had seen for 50 years

The cracks are showing everywhere in a fragile land now doubly cursed by the extremes of conflict and climate change.

The increase in temperatures in the Sahel are projected to be 1.5 times higher than the global average, says the UN, external.

"It hasn't been on our radar screens," says Peter Maurer, the President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

"We often look at arms and armed actors, and maybe at underdevelopment, but now we see that climate change is leading to conflicts among communities and this is a different kind of violence."

A gathering storm

Mali has a major UN peacekeeping mission as well as a multinational counterterrorism force to combat the rising threat of extremist groups across the Sahel linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State fighters.

Last year also reportedly saw the highest death toll from violence against civilians since the crisis of 2012 when Islamist groups occupied major cities in northern Mali including Timbuktu.

But behind this danger, there is another gathering storm.

The Sahel region - which includes Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania - comprises some of the world's poorest and most fragile states, and is regarded as the most vulnerable to climate change.

On a visit to northern Mali with the ICRC, it was startling to see how the consequences of climate change are woven through the fabric of lives in what has always been a harsh existence on the edge of the encroaching Sahara desert.

"The fragility of Mali stares you in the face," remarks Mr Maurer as we stand, surrounded by a vast crowd, in a cramped camp for families fleeing insecurity and hunger in communities across northern Mali.

"The whole attention of the international community is on high visibility conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, but the fragility here has lasted for decades."

Decreasing water levels are creating tensions between herders and farmers

Mali is now lurching between droughts and floods. They are both lasting longer and inflicting a huge cost on crops and livestock.

And that means farmers and nomadic herders, from different ethnic groups, are facing off over shrinking resources.

"There've always been small clashes between cattle herders and cultivators but water levels are decreasing and that's creating a lot of tension," explains Hammadoun Cisse, a herder who heads a reconciliation committee trying to mediate between communities.

And Islamist groups are also fuelling these fires by meddling in this combustible mix.

"They come in as protectors of communities and then try to impose their way of living on us," explains Mr Cisse.

"We don't accept this kind of Islamic culture with jihadi ideas so this creates another conflict."

Every story we heard in northern Mali was a tale of multiple threats, all terribly tangled.

A harsher existence - quantified

Temperatures across the Sahel have increased by nearly 1C since 1970, says the International Institute for Sustainable Development, external.

The increase in temperatures in the Sahel are projected to be 1.5 times higher than the global average, says the UN, external.

Roughly 80% of the Sahel's farmland is affected by degradation, including soil erosion and deforestation, estimates the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN., external

"We lost all our livestock in the drought in the 1970s and had to move to the city," Rabiatou Aguissa says as she crouches on a plastic stool in a dusty walled compound in Timbuktu.

A mother of eight children, she's also lost her husband.

"His little brother joined an armed group and he was so upset, he died of his trauma," she recounts as she readjusts the striking indigo cloth folded around her head.

Next to her, there's another reminder of a life in little pieces.

Thumb-sized packets of salt, onions, dried fish and tomatoes are assembled on a small metal tray, ready for sale on the roadside.

Two knitting needles poke out from the pile - another tool to try to make ends meet.

Animals died one after another

And in her narrow walled compound - and everywhere else we went - the gaggles of giggling children are another signal of what lies ahead.

Populations in the Sahel region are doubling every 20 years, every generation more fragile than the last.

The World Bank says this region is falling behind every other in the global battle against poverty.

Armed groups recruit young herders whose animals have died

We meet 17-year-old Younoussa at the Centre for Transit and Reorientation in Gao, a rehabilitation home for young boys who had been forcibly recruited into armed groups.

Nearly 50 young men, aged 13 to 17, are tucking into breakfast when we arrive.

Younoussa tells us he became a shepherd at the age of 13 but many young boys start tending the herds as early as nine or 10. Like all too many young Malians, he's never been to school, only Koranic classes.

He tells us insecurity forced his family to flee their home but he stayed behind to watch over their livestock.

"But there was no rain, and nothing for the animals to eat. They died, one after the other.

"To survive, I had no other choice but to join a group with guns," he tells us.

He details how he earned the equivalent of $3(£2.33) a month, working in the kitchen and manning checkpoints.

Most boys don't like to admit whether or not they fought.

"I don't want to be with an armed group," Younoussa says, his face visibly saddening. "I want to be with my family again and get a job."

Farmers are urged to think beyond their own families

Mali's dangerous mix can seem overpowering, but there are glimmers of hope.

With almost all Malians living off the land, that's where the fight back has to start.

"Farmers are not alone," says Sossou Geraud Houndonougho, who works on water and sanitation for the ICRC in the city of Mopti.

"We have to teach them not to just plant their own garden for their own family, but to work together to plant a forest for their community, for their future," he explains.

And from the mediator Mr Cisse, a plea for dialogue: "We should sit down and talk and see what we can do, not with arms but discussion, to narrow the gaps between us."

We see promising examples, at a local level, which show us peace is possible and there's a lot of energy to respond to climate change," assesses the ICRC's Mr Maurer. "But it's clear to me they won't cope unless there is solid support from the international community which isn't just through a security lens."

And the clear message from Mali is time is running out.

- Published8 October 2018

- Published11 December 2015

- Published30 November 2015

- Published20 September 2013

- Published28 July 2023