COP 21: Five ways climate change could affect Africa

- Published

As the UN climate change summit in Paris enters its final scheduled day, delegates from 196 countries are desperately trying to hammer out a deal, which could fundamentally alter the future of the planet.

Fifty-four African nations have adopted a unified position, calling for, external an agreement to limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century.

It is a more ambitious target than the 2C previously favoured by many developed nations and which is generally regarded as the gateway to dangerous warming.

Africa is expected to be one of the continents hardest hit, external by climate change, with an increase in severe droughts, floods and storms expected to threaten the health of populations and economies alike.

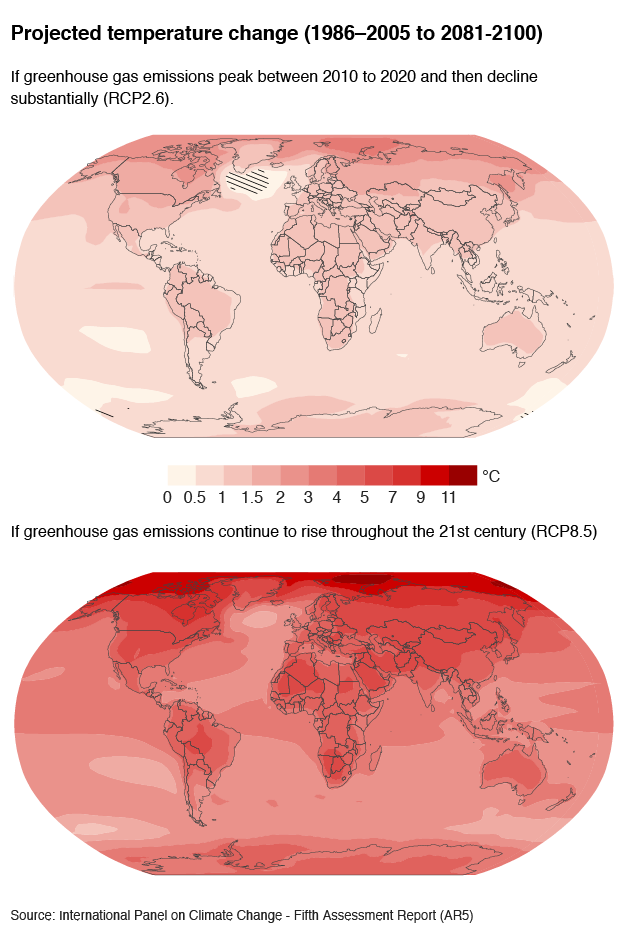

Part of that vulnerability is simply down to geography - already the hottest continent, Africa is expected to warm up to 1.5 times faster than the global average, external, according to the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) - the recognised global authority on climate science.

However, it's not just about where people live, but also whether they are prepared for what's coming.

With one in four people, external in sub-Saharan Africa still living in extreme poverty, hundreds of millions of people do not have the same safety net afforded those in wealthier, industrialised nations.

For a continent which has barely contributed to climate change, many argue that Africa will bear a disproportionate burden.

Even today, during a period of unprecedented industrialisation on the continent, Africa accounts for less than 4% of the world's annual greenhouse gas emissions, which experts say are responsible for global warming.

Here are some of the key ways the IPCC predicts climate change will affect Africa:

1. Farming will mostly become harder

The IPCC says it has "high confidence" that rising temperatures and unpredictable rains will make it harder for farmers to grow certain key crops like wheat, rice and maize (corn).

For example, it predicts that by 2050, yields for maize in Zimbabwe and South Africa could decrease by more than 30%.

Cattle are already dying from the drought currently ravaging southern Africa

SA grapples with worst drought in 30 years

Namibia on frontline of drought battle

Can Ethiopia cope with worst drought in decades?

One prominent climate scientist has used IPCC data to predict that by 2100, Chad, Niger and Zambia could lose practically their entire farming sector, external due to climate change.

This scenario is especially worrying when you consider that, according to the World Bank, external, agriculture employs two in three people in sub-Saharan Africa and accounts for a third of GDP.

2. But there will be some new farming opportunities

When it comes to farming, climate change may take with one hand and give with the other.

So, as it becomes harder to grow maize, external in southern Africa, it could become easier to grow it in the highland areas of East Africa in countries like Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania, though the overall picture for cereal crops in Africa is still a pessimistic one, the latest IPCC report says.

Cassava has been described as the "Rambo of the food crops"

The challenge to agriculture may also force farmers to be more savvy with their choice of crops.

If climate change means it no longer makes sense to grow maize in certain regions, another staple, cassava, a root vegetable which has a "hardiness to higher temperatures and sporadic rainfall" and is already widely consumed on the continent, could provide a viable alternative, external, it says.

How temperatures have risen since 1884

3. Malnutrition

Food insecurity, one of the key threats from climate change, will necessarily have a knock-on impact on people's health.

The IPCC reports that in Mali by 2025, 250,000 children are expected to suffer stunting, external, or chronic malnutrition, and that "climate change will cause a statistically significant proportion" of these cases.

Although the rate of under-nourishment in sub-Saharan Africa is coming down (it now stands at just under 1 in 4 people, external), the overall numbers have increased because of the rapid birth rate in recent decades.

By 2050, the population of sub-Saharan Africa is expected to more than double to 1.9 billion, external. That means even more mouths to feed at a time when the agricultural sector could well be struggling.

4. Malaria

The IPCC admits that "the complexity of disease transmission" makes it incredibly difficult to say which diseases may become more or less prevalent as a result of climate change.

But it does offer one confident prediction for the highland areas of East Africa, which are among the most densely populated on the continent.

According to the reports' authors, it is not only maize crops which are likely to benefit from the warmer temperatures, but malarial mosquitoes, causing increased epidemics of Africa's biggest killer, and introducing the disease to altitudes above 2,000 metres, which have so far been considered out of harm's way.

More than half a million people in Africa are estimated to have died from malaria in 2013

This new threat looms even though Africa has managed to reduce its malaria mortality rate by more than a third, external since the turn of the century.

5. Water shortages

One of the biggest threats facing the continent is also one of the hardest for scientists to definitively pin on climate change.

Water scarcity is driven by so many other factors, such as population growth, rapid urbanisation and changes to the way land is being used, that it has not yet been possible to figure out exactly how climate change will add to the mix.

Added to this, many African countries are already under high levels of "water stress", and 95% of farmed land in sub-Saharan Africa is estimated, external to be rain-fed.

The worst drought in 30 years has left one in three people in Botswana without enough water

"Water is life - with no water, Africa will be a dead continent," Opha Pauline Dube, Associate Professor at the University of Botswana and review author of the latest IPCC Africa report, external, told the BBC.

"Further water scarcity will negatively affect food production, trigger several diseases and worsen energy shortages which are already constraining development in many African countries," she adds.

Unreliable rainfall in the future will also play a big part in any crisis over water resources, but frustratingly again for scientists, it is much harder to make confident predictions about rain than it is about temperature.

The IPCC has predicted that rainfall is expected to decrease in northern Africa and parts of southern Africa.

Despite this uncertainty, three contributing authors to the Africa report told the BBC that changes in rainfall were the single impact of climate change on the continent which they were most worried about.

Africa will need to act to reduce man-made climate change as well as putting in place strategies to deal with those which cannot be avoided, but it is not going to be cheap.

Flooding may become more frequent and severe as a result of climate change

The continent will need $20-30bn every year, external for the next two decades, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB), and African negotiators will be looking to developed nations in Paris to make firm financial commitments as well as agreeing to curb emissions.

In the words of AfDB president Akinwumi Adesina last week at the summit in Paris:

"Africa has been short-changed by climate change. Africa must not be short-changed by climate finance."

UN climate conference 30 Nov - 11 Dec 2015

COP 21 - the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties - will see more than 190 nations gather in Paris to discuss a possible new global agreement on climate change, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the threat of dangerous warming due to human activities.

Analysis: Latest from BBC environment correspondent Matt McGrath

More: BBC News climate change special report

- Published9 December 2015

- Published30 November 2015

- Published10 November 2015

- Published29 November 2015

- Published13 April 2014