How do the police keep an eye on VIP stalkers?

- Published

This week's visit to Britain by Pope Benedict XVI will involve a major security operation. One element of that is a little-known unit which monitors the activities of "fixated individuals". How many are there and how dangerous are they?

In the run-up to the Pope's visit this week a little-known unit will have been especially busy.

The Fixated Threat Assessment Centre (FTAC) was set up in 2006 and has a £500,000-a-year budget from the Home Office and Department of Health.

Last week, at a briefing on the policing of the Pope's visit, Meredydd Hughes, who is co-ordinating the police operation, admitted FTAC would have been involved in monitoring certain individuals.

Mr Hughes, who is also Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police, said: "These are fixated individuals. They either believe they are the true Pope or are harbouring a grudge against him."

There have been at least six attacks on pontiffs over the last 50 years.

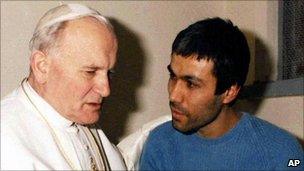

Most of the attackers were psychotic although the motivation of the most well-known, Mehmet Ali Agca, who shot Pope John Paul II, remains in doubt even to this day.

FTAC is made up of nine police officers, four forensic community mental health nurses and several forensic psychiatrists and was hailed as the first joint mental health-police unit in the UK and a "prototype for future joint services".

It is not known how many people in the UK have fixations but it is estimated the Royal Family alone receives 10,000 letters a year from mentally ill people.

FTAC has around 1,000 referrals to it every year and filters out half of that number fairly quickly.

Its remit includes Royalty and politicians but not actors, sports figures or other celebrities who are frequently stalked.

FTAC's senior forensic psychiatrist, Dr David James, has studied dozens of attacks on British and European politicians and dignitaries by people suffering pathological fixations.

Adelheid Striedel is a classic example.

For years she had been trying to get politicians in Germany to do something about secret underground "killing factories".

She claimed people were being abducted, chopped up and turned into robots, with the left-overs being turned into sausages.

It may sound far-fetched but in 1990 her delusions led her to stab Social Democratic Party leader Oskar Lafontaine in the neck. She missed a main artery by a millimetre and he survived.

The roots of such obsessions are usually extremely complex.

Dr James and his colleagues have identified several different types of fixated individuals.

The largest number (about 48%) are "pursuing justice", while 13% are suffering from deluded identity and may believe they themselves are the real Pope or the rightful heir to the throne.

Others are requesting or offering help; seeking sex or friendship or simply looking for fame.

The motives of Pope John Paul II's would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, are still a mystery

A significant minority - 13% - are so chaotically deluded that their motivation cannot be readily discerned.

FTAC eschews publicity and maintains a very low profile but Dr James wrote an article in the journal Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health.

He wrote: "Assessed threat levels were reduced to low through FTAC interventions in 80% of cases.

"Much of the threat engendered by these people arises in consequences of the misery or terror caused by their symptoms.

"They are seeking relief, albeit in misguided and dangerous ways: FTAC provides this for them where other services have not done so. It is the suffering individuals and their families who almost certainly benefit most from FTAC's work."

While the majority of such individuals are fairly "harmless", in the last 30 years some of that "small minority" have gained infamy worldwide.

They include Mark Chapman, who assassinated John Lennon, and John Hinckley junior, whose obsession with Jodie Foster led him to try and kill President Reagan.

But some critics fear FTAC could lead to people being "sectioned" under the Mental Health Act on the orders of the police rather than medical advice.