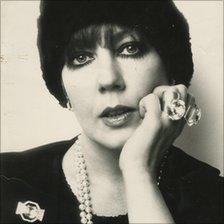

Molly Parkin: Fashioning her own career

- Published

Molly Parkin lives in sheltered accommodation in Chelsea but says she prefers it to her 51 previous homes

"It isn't what you've done that you regret, it's what you haven't done," says Molly Parkin.

Based on that premise, it must be rather hard for her to have any regrets at all.

Self-proclaimed national treasure, painter, former agony aunt, award-winning fashion editor, theatre performer, erotic author with a dizzying string of former lovers, this 78-year-old has detailed some of her exploits in a memoir, Welcome to Mollywood.

Her own motto for dressing is to rise each morning and "throw on whatever's nearest, just as long as it clashes" and it was this life-long extravagant style that led her to catch the eye of the fashion world.

In 1964, faced with a lull in her painting career, she was courted by Nova magazine, becoming its fashion editor, before moving on to Harpers and Queen in 1967 and then the Sunday Times in 1969.

Voted fashion editor of the year in 1971, just one of several awards from the fashion world, she quit the industry soon after, turning down many high-profile offers to return elsewhere, leaving it behind forever.

"Fashion was never my world, it's a cruel and superficial world. I never liked it, I wasn't happy in it, although they lauded me with all the distinctions and awards. It wasn't a world I wanted to be in. It was a relief when I left it."

Such was her unease with the fashion industry that she quit the first two editorial posts without any financial compensation, and worked without a contract at the Sunday Times. Her wayward dealings with money would come back to haunt her.

She was given a chunky, red plastic desk by the Sunday Times when she left, which she still uses now. The adjacent wall is covered with pictures of friends, family and David Beckham in his pants.

Molly was made fashion editor of the Sunday Times in 1969

Molly is brimming with gripping anecdotes of working with the great and good, but her experiences are underpinned by much darker elements, including her sexual abuse by her father, which she kept a secret until she was in her 60s.

The unflinching detail of her father's behaviour towards her as a child, which she describes in her book, makes for painful and uncomfortable reading, along with the physical beatings he often administered. It's a difficult process for both reader and author.

"It was searing, that experience of writing about it, so much so I had to have a bucket in order to vomit into as I wrote," she says.

"And even that physical exorcism of him was a healing process. The writing of this book has allowed me to come to total compassion and forgiveness for this man."

She nimbly nips around her cluttered flat, mainly one large room in sheltered accommodation in London's Chelsea, where she has lived since going bankrupt several years ago, the latest of the 52 homes she has lived in as an adult.

The place is full of large piles of books, paintings, ornaments, clothes, and all sorts of stuff, with shoes lurking and leaping out to trip any feet navigating the narrow walkways between it all.

She has covered everything in beautiful, if eye-watering, colourful throws, creating richly-explosive mounds all over the small space. It's rather like being inside a melted rainbow.

As she makes a herbal tea in her tiny kitchen, she introduces a large Madonna, two Buddhas and some other religious artefacts, in what she describes as her "spiritual corner".

Born in the mining village of Pontycymmer, south Wales, in 1932, she talks of once living in mansions, being showered in gifts by rich lovers, including a vintage Rolls Royce from the year of her birth, bestowed by "a besotted aristo".

But all that has now gone, her boutique on the King's Road in Chelsea and her Belgravia restaurant merely distant memories. But at least she managed to conquer the demons of her drinking.

"I used to go to three Alcohol Anonymous meetings a day, just to keep out of the bars," she says, now dry for the past 24 years.

She also puts her many fiancees partly down to her alcoholic haze.

"I don't know whatever made people think I'd make good wife material, or that their mothers would like me. They would always invite me over for tea, and then I wouldn't hear from that boy again," she chuckles.

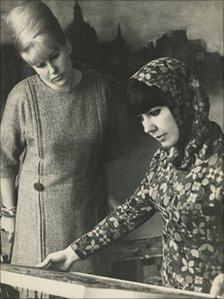

Molly (right) is seen here in her Chelsea art studio in 1961

"I did sit down and started to count the fiancees I'd had. I got to 18 and I thought 'Oh, stop it Moll'.

"You must remember I was a boozer, darling. At the end of the second date - sometimes the first - the person would say 'I'm passionately in love with you Molly, will you marry me?'

"Because I was drunk I'd say: 'That sounds fun.'"

And what of modern fashion? After working with photoshoot budgets that warranted security guards to watch over the precious gems she'd ordered from Bond Street jewellers, what catches her eye now?

"I don't see anything enthralling in the fashion reportage now, not as I did, breaking new ground.

"I like to see fashion seeping all down to youngsters. The greatest movement now in fashion is Primark, because of the cheapness, although the place horrifies some people."

She also extols the virtues of street markets and buying from charity shops, whose clothes she cuts up to make her own garments, "because you're helping charities and I like the concept of that."

She adds: "I am a humanitarian. Above and beyond even humanitarian, a humanist is what I am."