Soldier turned teacher talks life lessons

- Published

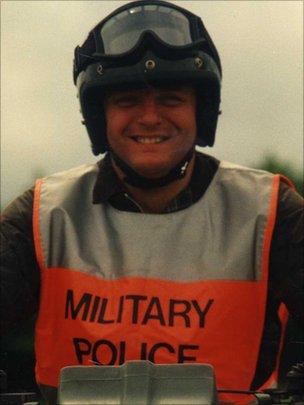

Steve Priday in a former life

Former members of the armed forces are being told, in Lord Kitchener style, that their country needs them.

But, as set out in the government's education White Paper, they are not being asked to return to the front line but to train for the classroom.

For the past two years, Steve Priday has been a teacher at Bedminster Down School in Bristol.

In a former life the 41-year-old was a police officer and, before that, he spent 14 years in the Royal Military Police, serving his country in countries such as Iraq, Kosovo and Northern Ireland.

He had plenty of experience of teaching before going to Bedminster, first with the Army where he drilled recruits in physical education, weapons and first aid, and then with the educational charity Skills Force.

It offers instruction and mentoring, mainly by ex-armed forces personnel, and Mr Priday spent seven years working with 15 and 16-year-olds in inner city Bristol schools.

He said the students were "challenging" but Skill Force's focus on life skills and more personalised approach got through to them.

"Communication, problem solving, team working - these are skills which the forces are particularly good at. We were teaching these skills in the way we had been taught," he said.

"It was not a boot camp. It was about the pupils being able to relate to us as real people with real experiences."

Along with five other Skills Force instructors, he gained his certificate of education after two years of night school.

He now teaches personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education and a BTEC first diploma course in uniformed public services.

Got a gun?

The father-of-one describes himself as a "very, very different" teacher, unencumbered by years of academia.

"I think I bring a very different skill set," he said. "I will put my hand to anything. I will do anything that's asked of me.

"I do things slightly differently. I work with really motivated and intelligent colleagues who are really inspirational and I hope some of the things that I do make them think."

Mr Priday spent four years in Northern Ireland

He said the pupils were more awestruck than frightened of him at first.

"They were very inquisitive. Have you ever shot anyone? Have you got a gun? Those kind of questions started to break down barriers and helped formed relationships.

"The awe has worn off and for me it's still all about relationships and teaching those basic life skills. Those skills help them in every other lesson."

He said he learned his "very simple style" of delivery in the military and his four principles of teaching are based on the EDIP mnemonic - exploration, demonstration, imitation and practice. Back then he used it to teach recruits how to clean a gun, now to teach his pupils interview techniques.

Mr Priday, who is also a special constable with a specialist search team, said the most important skill from his military career that he has carried over into teaching is tolerance.

"You have to be pretty thick-skinned and not take things too personally," he added.

Mr Priday said the general view of "squaddies" as practical but not very intelligent was "extremely outdated".

"Our servicemen and women work with some of the most hi-tech equipment in very hostile situations and environments," he said.

"They do so instinctively with a measured approach and calmness. There are many people that do not have an aptitude for teaching - both from the armed forces or civilian life. This does not make them in any way less intelligent. Teaching is a vocation that suits some, not all."

'School of hard knocks'

As set out in the White Paper, the government wants to establish a new programme to attract "natural leaders" from the armed forces into England's classrooms.

He still works as a special constable

Similar to the US Troops to Teachers scheme, which the Conservatives praised in opposition, former troops will be offered sponsorship to retrain as teachers.

Marius Frank was the headmaster who took Mr Priday on. He is now the chief executive of education charity Asdan, which provides programmes and qualifications aimed at giving pupils skills for learning, employment and life.

While welcoming the White Paper, which aims to double the number of high quality graduates becoming teachers, Mr Frank said sometimes you had to look beyond the brightest to find the most talented.

"It's about skill, talent and the ability to communicate with young people," he said.

"When you are working with the bottom 20% of young people who are disengaged for a variety of reasons, you need individuals with flair and talent to work with them."

Mr Frank, who was the head teacher at Bedminster for 10 years, said Mr Priday had what he and the school needed.

"Bedminster was in a challenging social area and attaining GCSEs did not light the flame of many students," he said.

"Education should be far more important than sitting a volley of two-hour exams. Schools should prepare kids for life and using people like Steve Priday prepares people for life.

He added: "Members of the armed forces have a nuggeted life experience born from the school of hard knocks and it's why they instantly connect with these young people."

Sam White, 16, says Mr Priday's PSHE lessons are "really fun" and he even gets the "naughty kids" in the class to do work.

"I learn a lot more with him than I do with other teachers," he said. "He does lots of activities. He's a really nice bloke and he's always happy.

"If more people had him in their schools, it would make learning a lot easier."

Jordan Howe, 15, takes Mr Priday's uniformed public services class. He wants to join the RAF police and so, while he naturally finds the subject interesting, he also praises the lessons for being clearly set out from start to finish.

"He's much more practical with his lessons and he uses his experiences within the lessons," he said.

When asked if people stopped running in the corridor when they spotted Mr Priday coming around the corner, he simply said: "I think people are better behaved because of his background."

- Published24 November 2010

- Published24 November 2010

- Published22 November 2010