Analysis: Cutting prison numbers

- Published

Waiting for a fresh chance at Feltham YOI

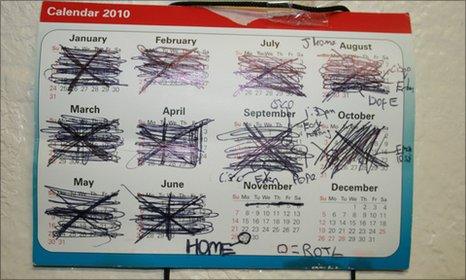

Frankie had a date ringed on the calendar on his cell wall: 29 November.

Guilty of robbery, the 17-year-old was sent to Feltham Young Offenders' Institution. But he spent months preparing for release on the specialist Heron wing, being coached in how to be a good citizen.

As release day approached, Frankie studied computing, aiming to get into college and to one day work in the UK's video games industry.

"There's no chance I'll reoffend," he said, as the day approached.

"Definitely, 100%. I have had a lot of support here. Now I will think twice before I act. I was in prison last Christmas. This Christmas, I'm with my family."

The 30-bed Heron Unit has dealt with 120 young men in its first year. Inmates have to demonstrate a genuine willingness to change their lives. But in return, they get specialist help from extra staff, including "resettlement brokers". These experts work with the offender on the inside - and then maintain that contact after release.

The brokers' job is to ensure that the former offender gets into college and housing or receives whatever other solutions they need to chaotic lives. It's partly mentoring - but a lot of no-nonsense monitoring and pressure to reform.

Almost eight out of 10 young offenders leaving Feltham go on to reoffend within two years. In its first year, Heron's reoffending rate has been 14%, with a further nine young men removed from the scheme while still inside.

Heron's resettlement brokers are one of a number of key projects that have been emerging as policy makers look for new answers to sentencing and jailing inmates.

And it's the mind-boggling social and economic costs of criminal justice that Justice Secretary Ken Clarke says he wants his green paper to slash in a "rehabilitation revolution".

The average annual cost of a prison place is now more than a place at Eton and hits almost £55,000 at intensive and challenging environments such as Feltham. Those costs as a proportion of all criminal justice spending have been rising over 20 years, with the prison population at near record levels of roughly 85,000.

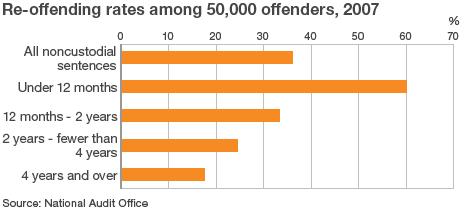

National Audit Office figures , externalshow that 60% of inmates held for a year or less go on to reoffend - and that has an estimated cost to the country of between £7bn and £10bn.

But at the same time, the Ministry of Justice's budget is projected to be cut by almost a quarter over the next four years. Thousands of jobs will go as £2bn is lopped from legal aid, courts, prisons and probation.

So when it comes to dealing with criminals, we can't afford to keep locking them up.

But if there is no new government money, can sentencing and rehabilitation be reformed?

The ministry insists that the "dangerous and serious" offenders will still be locked up - but there is going to be a concerted focus to find fresh ways to stop lower-level offenders from embarking on long and disruptive lives of crime.

With this idea as a starting point, Mr Clarke says judges should be deciding on sentences, not newspapers or politicians.

Rather than set absolute jail terms, he argues, policy makers should focus on protecting the public by establishing what levers judges can pull to stop someone offending, rather than a one-size fits all approach.

That's the thinking behind Mr Clarke's controversial decision to drop a Conservative election pledge to try to jail more people who carry knives.

And the government is also promising a greater focus on tackling drug and alcohol abuse, a rethink on how to deal with mentally-ill offenders and efforts to get more ex-offenders into jobs. London Mayor Boris Johnson is already lobbying the capital's businesses on that point, piling pressure on employers to give people like Frankie from Feltham a chance.

The short term aim is a modest 3,000 fall in the prison population by 2014-15. But the longer-term dividend could be massive.

But who will pay for the reforms if the MOJ's budget is being cut?

The Heron scheme at Feltham, for example, has specific funding that runs out in 18 months' time.

Another closely watched London scheme, the Diamond Initiative, conducts similarly intensive monitoring and mentoring of adult offenders coming off short-term sentences.

The first evaluation of that £11m initiative, external has been extremely promising, reporting a halving in the reoffending rate among the targeted offenders.

Other schemes being investigated include pilots of "Integrated Diversion and Offender Management" (IDOM) teams.

This basically means getting the police, probation and other agencies, such as drug treatment bodies, to work in the same office. The same people doing the same job they have always done - but in a joined-up way that makes the difference.

In one case cited by the West Midlands IDOM pilot, external, a 15-year-old girl was caught carrying a knife into school. In other areas, the teenager might have been heading to the courts. In this case, the IDOM team put her into some intensive counselling that made her change her behaviour. They say she hasn't reoffended since.

However, with the Ministry of Justice cutting thousands of jobs, a huge bet is going to be placed on the private or voluntary sector - and radical proposals for "payment by results".

Peterborough Prison has also seen the roll-out of Social Impact Bonds, external, a rehabilitation programme funded by City cash.

Investors buy into a bond which funds specialist reoffending work by recognised expert charities. If reoffending rates fall, the investors get a dividend from the Ministry of Justice.

Ministers insist the reforms are not being driven by cost-cutting but by a flexible approach to prisons and rehabilitation that is more constructive than simply "warehousing" criminals until its time for their release.

But Harry Fletcher of probation union Napo says that professionals are very sceptical.

"This Green Paper is not primarily about value for money or building on 'what works'. It is motivated by an ideological wish to drive down costs and introduce the private sector," he says.

"The [payment by results] scheme is predicated on the private sector raising massive amounts of capital from investors. This will only happen if successive pilot schemes give positive results. Because of the nature of offenders, with chaotic and troubled lifestyles, this is highly unlikely to happen."

- Published7 December 2010

- Published10 September 2010

- Published20 October 2010