Max Mosley: Life in the fast lane

- Published

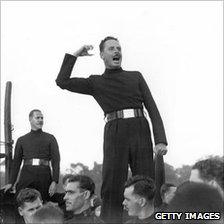

Max Mosley has had to weather a considerable storm

The controversial ex-motorsports boss Max Mosley has spent most of his life trying to shake off the burden of his family name and its strong ties to Nazism.

Sacrificing a career in politics, he chose the apolitical world of motor racing in which to become something of a success story.

That was until he found himself, in his late 60s, picking up the pieces of his life after his colourful sex life was splashed across a tabloid newspaper one Sunday morning.

The News of the World alleged he had indulged in a "Nazi-style" sado-masochistic orgy with five prostitutes, but Mr Mosley, now 71, successfully sued them and began a lengthy legal battle to try to force newspapers to warn people before making allegations about their private lives.

Pursuing this at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has once again thrust Mr Mosley into the public eye and into our papers, with interest heightened by his famous name and family history.

On his first day giving evidence at the High Court, the former president of the International Automobile Federation said: "All my life I have had hanging over me my antecedents, my parents."

Those parents were Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists in the 1930s, and Lady Diana Mosley, a Mitford sister described after her death by one newspaper as an "unrepentant Nazi".

When both were jailed for their views during World War II, Max Mosley had to endure separation from his mother at a very early age. He was only fully reunited with her at the age of three.

His fluent German stems from his teenage years, where he spent two years being educated at a German school.

Max Mosley's father Oswald led the British fascists before WWII

He was actively involved in right-of-centre politics in his younger years, campaigning for his father and later standing, unsuccessfully, as a candidate for Oswald Mosley's post-war party, the Union Movement.

Given the choice, Mr Mosley has said, he would have chosen politics as a career.

"But because of my name, that's impossible."

After training as a barrister, Mr Mosley decided to make his career in the glamorous, but apolitical, field of motor racing where, as he once told an interviewer: "I've found a world where they don't know about Oswald Mosley."

Secret interest

It was around this time that he began to indulge a secret interest in sadism and masochism which had started, Mr Mosley told the court, at "quite a young age".

Defending his actions, he said: "I fundamentally disagree with the suggestion that any of this is depraved.

"I think it is a perfectly harmless activity provided it is between consenting adults who want to do it, are of sound mind, and it is in private."

Diana Mosley's wedding was held in Joseph Goebbels' house

But up until the News of the World's article, it was a secret activity that his wife of 50 years, Jean Taylor, and two children, Alexander and Patrick, were unaware of.

He said his wife had initially thought he had the edition printed as a joke.

In a BBC interview, he said he was unsure whether his wife had got over it. "It's something that never goes away."

He said he regretted "the effect on my wife and family", adding: "I can't imagine anything worse than being the son of somebody and seeing those sorts of pictures in the newspaper."

He even suggested the scandal could have contributed to the problems of his son Alexander, who died aged 39 in 2009 from a drugs overdose, after years struggling with addiction. "I've no doubt it made the situation worse," he said.

In the workplace, Max Mosley's legal training and undoubted political skills propelled him up the motor sport career ladder, from a successful driver in the 1960s to head of the FIA in 1993.

But beneath the measured, suave exterior, he has been unafraid to use some direct methods - and language - to get his way.

Authoritarian streak

In 2007, he publicly called former world champion driver Jackie Stewart a "certified half-wit" after the Scot criticised his handling of the "spy-gate" scandal involving McLaren and Ferrari.

Former world champion Damon Hill said: "Certainly his style of presidency has a very strong authoritarian streak to it, which I think does intimidate journalists and people who work in the sport."

Along with his long-time associate Bernie Ecclestone, Max Mosley ruled F1 in sometimes controversial ways - even if many of the things he achieved had much merit.

Max Mosley regrets the effect the tabloid's expose of him had on his wife, front centre, and family

He has stated that his greatest achievement as FIA boss was to make F1 racing much safer.

As an amateur racer, who had competed in the 1968 Formula Two race at Hockenheim in which double world champion Jim Clark was killed, Mr Mosley had already been well aware of the terrible dangers of the sport.

His experiences as co-founder of March - a racing car manufacturer - during the 1970s and 80s bequeathed him a good practical knowledge of F1 technology.

From the mid-1990s Max Mosley set about bringing in wide-ranging changes: reducing engine capacity, introducing grooved tyres to reduce cornering speeds, redesigning circuits and ensuring there was more rigorous crash-testing of the cars' chassis.

Green issues

In addition he pushed for F1 to begin developing environmentally friendly technology, which could also be applied to road cars.

To this end, Mr Mosley put in place a 10-year ban on engine development, in order to ensure manufacturers spend more of their budget on "green" issues.

Although the moves were highly commendable, there was some suspicion that his motives were driven as much by the need for F1 to safeguard its future as they were for safeguarding the future of the planet.

After his unorthodox sex-life was exposed, Max Mosley's future within the sport looked precarious.

Although Bernie Ecclestone initially supported the determination of his friend of 40 years not to stand down, he later declared that he "should go out of responsibility for the institution he represents".

And a motorsport insider told the BBC that Mr Mosley's decision to hang on after the initial allegations demonstrated "a catastrophic lack of political judgement".

In refusing to go quietly, Mr Mosley demonstrated a stubbornness of character that had served him well at times in pushing difficult and complex decisions through the industry.

That trait revealed itself in his decision to take on a powerful newspaper in court - in the knowledge that further potentially embarrassing details about his lifestyle might emerge.

He also showed a certain audaciousness in his demand for unprecedented "very big" exemplary damages for breach of privacy.

At the High Court on 24 July, Mr Justice Eady did not make that award and instead awarded him £60,000.

The judge ruled there was no evidence of a Nazi theme so there was no public interest in running the story.

Now, ahead of his latest battle, he explained his motivation to change celebrity privacy laws: "You realise in an instant that everything you've worked for, everything you've built up, all the things you've done that you hope you're recognised for, are pushed to one side by something that's a very small part of your life, and in the big scheme of things totally insignificant, but blown up so that it defines you. And that to me is outrageous."

- Published10 May 2011

- Published11 January 2011