Urban v rural: Which is better?

- Published

- comments

Samuel Palmer's career shows a more complicated countryside story

The haunted face of the English romantic artist Samuel Palmer has been staring at me, his dark hypnotic eyes following me around. At odd times and in odd places, there he is again, questioning me about something.

My daughter has been writing a history of art degree essay on the self-portrait for the last few months and copies of the chalk drawing have been pinned up around the house. Samuel Palmer in the kitchen, in the bedroom, even in the bathroom. Then this week, when I thought the picture had been safely exported back to her student digs, I opened my morning paper and there he was again, still challenging me with that dead-pan gaze.

A new book on the artist is out this Friday, Mysterious Wisdom: The Life and Work of Samuel Palmer by the art critic Rachel Campbell-Johnston, and through the story of his strange career, she reveals something of the strained relationship that has long existed in England between the urban and the rural, between town and country.

Also just published is the Statistical Digest of Rural England, external, the annual government report which charts the contemporary relationship between urban and rural England through facts and figures. Here, too, one can see a sharp divide - but not in quite the way I had expected. More of that in a moment.

Palmer was a city boy by birth, but he was a dreamy and spiritual character who longed for rural escape. Campbell-Johnston paints a ghastly picture of industrialising England in the early 19th Century: "Huge, stinking slums spread unsanitary ghettos which developers ignored, an entire urban underclass was being created, its members grist to the economic mill." Small wonder, she suggests, that people like Palmer were fantasising about a simpler, ancient rural idyll.

"Here was a spiritual antidote to contemporary materialism; here was an era in which, it was wistfully imagined, the values which modernity was destroying could be rediscovered again. The towers of England's gothic churches stood like stone guardians amid its patchwork landscapes, stalwart survivors of a lost age of belief."

'Pastoral fantasy'

Is there more to the green and pleasant land?

The English countryside still has that hold on many of us, I think. As portrayed in countless tourist brochures, upon chocolate boxes and jigsaw puzzles, the sun-kissed landscape feels more "authentic" than the bland suburban housing estate or the shopping precinct. It still provides an antidote to the deadening commercialism of contemporary urban life.

As a young man, Palmer moved to Shoreham in Kent, determined to live the simple and authentic existence he assumed would be found in rural England. His drawings and paintings reflect a romantic vision which still shapes many people's mental image of the countryside. Campbell-Johnston describes it as a pastoral fantasy.

"As he wandered the fields of the fertile Kentish valleys, along wooded ridges and down sloping pastures, among orchards and hop gardens, by hayricks and cattle sheds, he beheld a landscape transfigured as if by some miracle of divine grace."

The reality, of course, was very different. The enclosure of common land was seeing the eviction of peasants from the fields that lay between them and starvation. The desperate search for food to feed their families resulted in thousands facing imprisonment, transportation or death. The agrarian and industrial revolutions were demolishing the English countryside as it had existed over centuries. But Palmer "failed to see the reality that lay right in front of him because he was looking straight through it in search of some higher truth".

Modern idyll

So, what do the graphs and tables tell us of the reality of rural life in England today? Before I looked at the statistics, I would probably have said that the idyllic vision instilled in our consciousness by Palmer and other Romantics like John Constable and Joseph Turner still means we overlook the poverty and sheer hard grind of rural communities, that city dwellers don't realise just how tough it is to make a living in the countryside, that we look straight through the privation because we want to believe in some Arcadian paradise.

What the data tells us is that the people of rural England are healthier, safer and better educated than their city cousins. They are less likely to be homeless, living in poverty, unemployed or a victim of crime and they will probably live longer too. Of course there are downsides to living in the countryside - with seclusion and space come inevitably higher transport costs, poor mobile phone coverage and slower internet speeds - but the stats defy any notion that the English rural scene is threatened. In fact, by almost any measure, life is better in the country.

A man in the town can expect to die a full two years earlier than his equivalent in the countryside, and it is a similar tale for women. The risk from dying early from cancer is significantly lower in rural areas, as are the risks from stroke and heart disease.

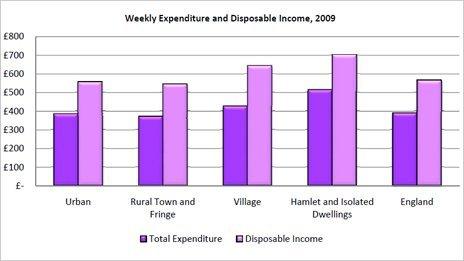

You are almost twice as likely to be the victim of violent crime in towns and cities, almost three times as likely to suffer a burglary. The proportion of the population living below the poverty threshold is 18% in the country and 23% in towns while people living in villages and hamlets have significantly higher amounts of disposable income (between £640 and £700 per week) than their urban neighbours (£555).

The weekly household expenditure bill offers a clue to lifestyle: village dwellers spend 20% more on alcohol and tobacco than city dwellers; 10% less on housing, water and electricity; 9% more on recreation; a little less on restaurants and hotels. Rural residents do spend more on transport - 18% of total expenditure as opposed to 15% among urban folk, and fuel poverty is obviously more of a problem in more isolated areas.

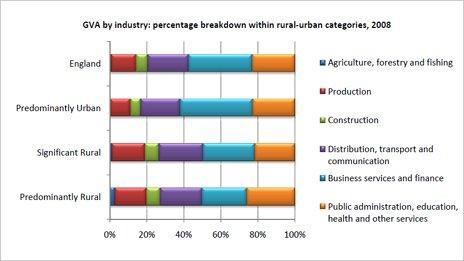

Employment rates are significantly higher in rural areas (78.0%) as opposed to urban districts (71.5%) and unemployment much lower. In 2009, one urbanite in 12 was out of work compared to one in 19 in rural areas. One table that surprised me shows how little of the rural economy is based upon agriculture these days. The dark blue bar that relates to farming, forestry and fishing is easy to miss.

Rural wage-packets are thinner than urban ones - median earnings in predominantly rural areas were £21,000 last year compared to £22,600 in predominantly urban districts, but taken as a whole, the statistics are a useful corrective to the notion that city dwellers have a cushier life than their country cousins.

Samuel Palmer's self-portrait was drawn before he left "horrid smoky London" for "that genuine village" in Kent. It is the face of a romantic teenager trapped in a brutal urban environment. Perhaps he has been urging me to question some of my assumptions about England's glorious and beautiful countryside: yes, it has significant challenges that a metropolitan elite might too easily overlook, but rural communities have not been abandoned or forgotten. If anything, compared to urban neighbourhoods, they are thriving.