Hearts and minds: London's street battle with al-Qaeda

- Published

- comments

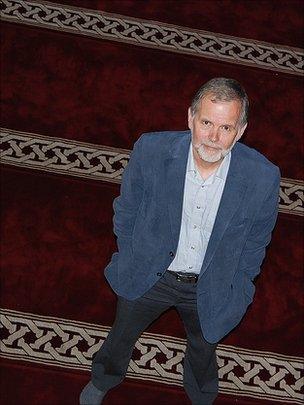

Bob Lambert, standing in the prayer hall at Finsbury Park Mosque

What have we learned since 9/11 about combating al-Qaeda's ideology? One former police officer tells his story of tackling terrorism's recruiters - and why he thinks the UK government has now taken a wrong turn.

It began in the backroom of a north London halal butcher's shop.

Unlike in the movies, with their spooky operations rooms, eyes in the sky, and a hero running through plate glass windows, the battle to oust Abu Hamza from his London power base was far more prosaic.

Bob Lambert, a former Metropolitan Police Special Branch officer, was part of the tight-knit team that turned around a mosque that had become one of the biggest security dangers in Europe.

Hamza, the radical cleric later jailed and now facing extradition to the US, had turned Finsbury Park mosque into his centre of operations - inciting hatred, identifying susceptible young men and, to all intents and purposes, providing a terrorism training camp less than five miles from Scotland Yard.

But while MI5 and counter-terrorism detectives worked away at the intelligence and evidence that ultimately brought down the preacher, Bob Lambert's role was to work out what would happen next.

Following 9/11, the then detective inspector and like-minded officers, persuaded Scotland Yard chiefs that they needed a specialist team called the Muslim Contact Unit. Its task was to hit the streets and identify the individuals, community leaders and organisations who could become partners in taking on al-Qaeda's message.

It was his job to find people he thought were brave enough to join an operational battle for the hearts and minds of young Muslims in London.

And so Lambert found himself holding a clandestine meeting in the butchers' with local Muslims who wanted help in dealing with Hamza.

Today, Finsbury Park mosque is run by trustees who Lambert helped to install - people who he says pushed Hamza's supporters and network from the streets.

'Enormous risks'

Sitting in Finsbury Park Mosque's general office (shoeless, in our socks, as is the practice) Lambert recounts the experience.

Abu Hamza: "Offered excitement" to vulnerable young men, says Lambert

"Special Branch policing needs its informants, its intelligence and its detectives," he says. "But we also needed something else - partnerships.

"Enormous risks were taken here at Finsbury Park," he says. "People in the community knew they were taking enormous risks by deciding to work with the police - and with Special Branch - while at the same time being part of a political campaign against the 'War on Terror'."

Over the course of five years, the MCU ran similar behind-the-scenes projects across London, identifying extremists and finding local leaders capable of marginalising them.

Bob Lambert argues that with the right support, bolder community leaders emerge who are prepared to work with the police, and engage and counter violent extremists. The intellectual - and physical - space available to the likes of Abu Hamza shrinks.

But the question is, who makes a suitable partner for the police? And Bob Lambert's answer to that question is what makes him so controversial

He concluded that many of the leading Islamist figures in London - who often harboured strong grievances against the West and Israel - could be partners. Why? Because they understood the complex Islamic arguments hijacked by Osama bin Laden to recruit for violent jihad.

But Lambert's critics say that these same groups are ultimately part of the problem.

Radical Islamist groups, go the arguments of thinkers like Ed Hussain, external, represent "them and us" separatism - and at worst are part of the conveyor belt towards terrorism. There is nothing to be gained in working with groups who they accused of being part of al-Qaeda family tree, they say.

"From my experience, are these groups dangerous militants? That's ill-deserved. It's unjust and these groups have been demonised," says Lambert.

"My critics say that my partners were akin to the BNP. What I'm even more convinced of now is that people like Abu Hamza are akin to the BNP because of the hatred.

"If I came across any Muslim group [who I worked with] that had genuine hatred towards the Jewish community, or the gay community, then I would concede the argument."

The Palestinian question

The most difficult - and emotional - issue in this debate is the question of Israel and the Palestinians. And the views of one the most influential Islamist activists in London demonstrate the problems Bob Lambert has had with his critics.

Palestinian-born academic Azzam Tamimi, a Hamas supporter, has defended suicide bombings in the conflict, describing it as a legitimate act of martyrdom in an unequal war. At the same time, he says he opposes al-Qaeda and urges British Muslims to engage in politics, urging them to get out and vote at general elections.

That does not wash with his many critics - and the same critics accuse people like Lambert of being an apologist for extremism.

Lambert says: "I would not support everything that Tamimi says. But I think you have to take into account the human dimension of where people like him are coming from.

"But people like him [here in London] are engaged in politics. Hamza hated politics - he hated people going on marches.

"When we could show to young people that here were some active Palestinian figures who were challenging the al-Qaeda narrative - and they were also prepared to work with non-Muslims - that, I believe, was the start of the solution."

And he says that the Muslim Contact Unit and its partners got results, persuading young men that the answers to their anger lay in politics rather than violence.

"I have interviewed individuals who have talked convincingly about a [former] attachment to Osama bin Laden's world view.

"I don't think that today they have abandoned the grievances that lay behind that - but I know also that they are now entirely comfortable operating in mainstream politics."

Bob Lambert uses his memoir to defend what he did between 2002 and 2007. He urges governments to work with radical, but non-violent, Muslim organisations. But as things stand he has lost the argument in Whitehall.

The MCU's work began before the government's Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE) strategy had got off the ground.

Developed in the wake of the 7/7 bombings, PVE has spent almost £80m on 1,000 Prevent schemes. Some 94 local authorities had cash thrown at them to find the right local people to fund in the battle against al-Qaeda.

But the hearts-and-minds policy was mired in Whitehall disputes and at one point lost many of the key thinkers - Muslim and non-Muslim - who had been recruited to run it. Nobody could agree on how it should achieve its aims.

Prevent has now been relaunched - and one very important element has changed: The groups that Bob Lambert says the government and police should work with are out in the cold.

The new policy has seen the withdrawal of funding for groups the government says are non-violent extremists - organisations that it says oppose "fundamental and universal" British values.

"All of the 40 or 50 Muslims who came to my retirement are all probably now classed as non-violent extremists," says Bob Lambert. "That's absurd. One minute they are partners, the next they are not."

The former Special Branch officer says his years in the force taught him that too much is at stake.

"It's in the nature of terrorism as a tactic that it only has to secure a small number of people in order to achieve its goals," he says. "I think we need to be much more creative about how we counter that."

Bob Lambert's book, Countering Al Qaeda in London, is published by Hurst.