Wiener Library relocates Nazi archive to new premises

- Published

Ben Brakow, the library's director, gave a tour of some of the more chilling exhibits

The world's oldest Holocaust museum has moved to a new home in London's Russell Square. As well as archiving documents from Jewish victims of repression, the museum also holds chilling examples of how the Nazis used games and books to indoctrinate Germany's youth with anti-Semitic values.

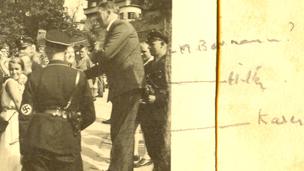

Karen, the pretty young woman in the photograph, looks excited, as one might when about to meet someone famous.

She is just visible among the crowd, her white summer dress contrasting with the black uniforms of the soldiers around her.

Standing on a wall nearby is Adolf Hitler, reaching out to sign her book, an English version of his Mein Kampf.

The photo in the Mein Kampf book shows Hitler, with Martin Bormann, meeting its recipient, Karen (left)

The full identity of the woman remains unknown, save for her first name written next to her image, but a pencilled note beneath says how the family, clearly English, were in Germany's Berchtesgaden when Hitler "came into the village, shook hands with tourists, signed standing up - in pencil!".

The book itself, complete with the photograph pasted inside its front cover, was later donated to the Wiener Library, where it now rests among thousands of other texts, documents and photographs about Holocaust survivors, its victims and perpetrators.

The library, the world's oldest Holocaust archive, has recently moved into a new home in Russell Square, having previously been based in Devonshire Street, and re-opened on 1 December. It also holds children's books, board games and other unusual items spawned as a result of 1930s Nazism.

The library's content first began to be collected in 1933 by Alfred Wiener, a German Jew. He fled in 1933 for Amsterdam following the rise of the Nazis and worked with others to collect information about events happening in Nazi Germany.

Ben Barkow, the library's director, says that because the archive began so early, it now holds many objects that are rare.

"Some of our items are so old that you can't collect them now, they're just not available. We have them because we were there at the time."It is far and away the largest and best collection on the subject in the UK, and one of the largest in the world.

"In the modern world, where within even the European Union there are serious problems with racism, with anti-Semitism, with hatred of Sinti and Roma people, there's a huge amount to be learned from looking at this period of history."

The collection was transferred to a premises in Manchester Square, London in 1939, with Mr Wiener making the resources available to British government intelligence departments.

Its resources have continued to document events of the Holocaust, Nazism and post-war episodes of anti-Semitism ever since, continuing past Mr Wiener's death in 1964 and carrying on today.

It was drawn on for the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals in 1946, the trial of Holocaust architect Adolf Eichmann in Israel in 1961 and more recently in 2000 for a case involving historian David Irving, who took American academic Deborah Lipstadt to court for libel after she branded him a Holocaust denier. Irving lost the case.

Among the more bizarre items held by the library are children's books and games, intended to imbue hatred and fear of Jews.

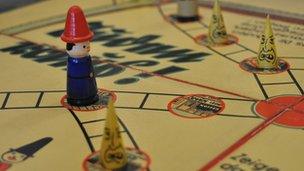

The Juden Raus! game asks players to remove Jews from a village, so they can go "off to Palestine"

One large board game is called "Juden Raus!" which means "Out With The Jews!". It requires the players to roll dice and move smiling, brightly-coloured figures about a village, picking up conical yellow figures - depicting Jews with grotesque faces - which fit on their heads.

The writing on the board declares that whoever carries six Jews out of their shops and properties and out of the village is the winner. It is a well-made, brightly coloured creation, and serves as a depressing reminder of man's ability to be fiendishly creative in his inhumanity to others.

Mr Barkow points out that the game was not produced by the Nazi party but was an opportunistic business venture by a German company, which simply seized upon the political mood of the country in the 1930s.

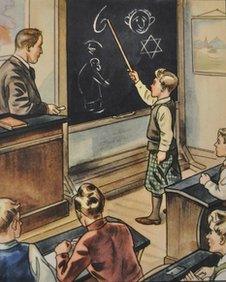

Other items at the library include a children's book called Der Giftpilz - The Poisonous Mushroom - which includes brightly coloured, grotesque depictions of fat, hook-nosed Jewish men making money from heroic-looking German peasants and noble Germanic housewives.

And another book has a metal optical contraption tucked inside its cover, with which to view photographic strips of German soldiers in heroic action. Looking through the stereoscopic device gives a crude 3D effect, another testimony to the Nazi passion for technological excellence.

Mr Barkow says the amount of anti-Semitic material produced in Germany, particularly that for children, left a deep imprint on the nation's society.

The Poisonous Mushroom tells children how to identify Jewish people

"A lot of these games and books for children were extremely clever, and the sheer quantity of it, the sheer inescapability, certainly meant it had an effect.

"It did mark people, by making them grow up to think a certain way, or needing a rocky road to walk in order to adjust to a life beyond the German regime, once it had ended."

The Wiener Library, which receives funding from a variety of sources including the German foreign ministry, has volunteers to help with cataloguing and preserving its archive. It has just lost its oldest, who died aged 99.

One of its current youngest is 18-year-old Felix Moritz, who is from Vienna in Austria and is spending his gap year working at the library.

"In Austria, the political right movement is rising again, so it's really important to think about our past and learn from it," he says.

"When I look at the Nazi ideology, I can't understand that way of thinking. We must question the things we hear, so we can become more tolerant."

- Published20 March 2011