Stephen Lawrence: The long road to justice

- Published

Gary Dobson and David Norris: Denied murder

It took 18 years, but the deceit, lies and public arrogance of Gary Dobson and David Norris have finally been exposed. They murdered Stephen Lawrence.

The cornering of Dobson and Norris followed woeful mistakes in the original investigation, failed prosecutions, a public inquiry that rocked the establishment, Acts of Parliament, and, critically, the determination of the family and a small team of untainted detectives to nail the suspects once and for all.

The pair have been convicted on what appears to be the slimmest of evidence - evidence the defence said was incapable of filling a teaspoon. But it was the quality of that material, rather than its quantity, that mattered.

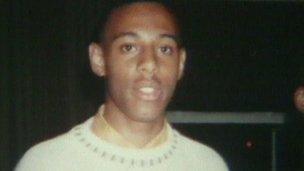

Stephen Lawrence, 18, was the victim of an appalling crime on 22 April 1993. He was waiting for a bus in Eltham, south east London, with his friend Duwayne Brooks when a group of white men of similar age rushed him.

One was heard to say "what what nigger" before a knife was plunged twice into the teenager, severing two arteries. He had done nothing to provoke his attackers.

Any family faced with the enormity of such a crime would expect the police to do all they could to find the killers.

But Doreen and Neville Lawrence, until that moment average hardworking Londoners, were failed. The later public inquiry made abundantly clear that they were failed because Stephen was black.

In pure policing terms, Stephen's death was not the most complex of cases to crack. It was little different to any other grim gang attack that even the most junior of detectives would be able to pursue.

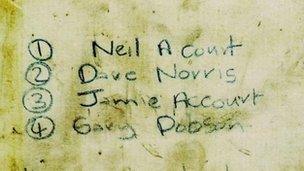

Tip-offs: Police were given leads by local people, like this note shown at the public inquiry

Tip-offs initially led the police to brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt and their friends, Gary Dobson, David Norris - the son of a then feared south London gangster - and then to a fifth youth, Luke Knight.

They were all said to harbour violent racist views - allegations that featured heavily in the public inquiry.

Arrests were made and clothing was seized - but only after the Lawrence family had held a news conference attacking the police for not acting.

Neil Acourt and Luke Knight were initially charged but the Crown Prosecution Service halted proceedings when it concluded that there was insufficient evidence.

Furious with the police failures, the family decided to go it alone with a private prosecution but the case failed in 1996. The eyewitness evidence of Duwayne Brooks was ruled unreliable and Neil Acourt, Gary Dobson and Luke Knight were formally acquitted.

Stephen Lawrence: Did nothing to provoke his attackers

That appeared to be the end of the road because nobody at that time faced trial twice for the same crime. But this was not the end of the story.

At Stephen's full inquest - four years after his death - the five friends refused to answer questions. The jury returned a verdict stating that the teenager had been "unlawfully killed by five white youths".

The pressure to solve the case continued and in February 1997 the Daily Mail used a dramatic front page to accuse the five of murder, inviting them to sue if they were innocent. All five men later went on television to deny any involvement in the murder but the critical moment was the change in government that year.

The new home secretary Jack Straw ordered a public inquiry - and it was Sir William Macpherson's damning conclusions, external that rocked policing.

Sir William was shocked by what he uncovered. He concluded that the police had failed in their basic duty to investigate until they could investigate no more because the Met was blighted by institutional racism.

Acts of Parliament

Sir William said his inquiry could not right the wrongs of the past. But his conclusions and recommendations were so important - and have been so broadly acted upon - that they played an essential role in securing the convictions of Dobson and Norris.

Firstly, the reputation of the Metropolitan Police was in tatters and its chiefs knew they had to raise their game to rebuild public trust.

Secondly, the inquiry prompted Parliament to introduce two important changes to the laws on equality and justice.

The Race Relations Amendment Act 2000, external imposed a duty on public bodies to promote equality. This extremely important legislation effectively means that bodies including every police force, local council and government department must show what they are doing to treat all people fairly.

Then the Criminal Justice Act 2003 , externalscrapped double jeopardy - the legal principle that prevented someone being tried twice for the same crime after being cleared at the first hearing.

These factors, combined with the public campaigning of the Lawrence family and the impact of a hard-hitting BBC documentary, meant that the case was not going away. And back in Scotland Yard, senior officers were looking at fresh ways to bring charges.

During 2006, the Met had turned around another seemingly failed case when a jury convicted the killers of 10-year-old Damilola Taylor.

The convictions were based on DNA evidence that had been missed during the first investigation.

Starting from scratch

The new Lawrence team at Scotland Yard brought in LGC Forensics to conduct a cold case review and to think along the same lines as the Damilola reinvestigation: review everything, assume nothing.

The Metropolitan Police's Alan Tribe was the scientific co-ordinator of the evidence review.

"The fact that it is a cold case - they always bring challenges," he said. "It means you have to delve back into the previous history of the exhibits and of the path they have taken.

"There had also been, in this case, a number of previous scientific examinations that hadn't yielded the evidence that we were looking for and found in this case."

The clothing seized from suspects was re-examined using techniques that were not available in 1993. And slowly, over the course of many months of tests, tantalising signs emerged.

Scientists found tiny blood flakes inside the bag that held Gary Dobson's jacket. The DNA extracted from the flakes matched Stephen Lawrence. That evidence was supported by fibres that had been transferred from the victim's clothes.

The biggest breakthrough was a tiny speck of blood dried into the weave of the jacket collar. Again, the DNA matched Stephen Lawrence. Further testing proved that the blood could have only soaked into the weave when it was fresh - and that put the jacket wearer at the scene of the crime.

Edward Jarman, the scientist who recovered the DNA, said this stain, only visible through a microscope, is the smallest piece of blood evidence used so far to mount a prosecution.

The defence argued that the stain was the result of contamination thanks to poor handling of exhibits down the years.

But the evidence to the contrary - hour upon hour of witnesses explaining how items had been moved, managed and stored - proved to be enough.

Jamie and Neil Acourt and Luke Knight appeared at the 1998 inquiry

So what of the other suspects in the case? The police's Lawrence murder investigation narrowed its investigations down to 11 individuals, but detectives have always believed that only five were involved in the attack.

Dobson, Norris, Neil and Jamie Acourt and Luke Knight have all at various points denied being the killers. Dobson told the trial he was at home when Stephen was killed, making toast. Norris said he did not know where he was on the night of the attack.

In 1999, the Macpherson Inquiry described the five as "evil", external and "infected and invaded by gross and revolting racism". It named them as the "prime suspects", saying they relied on a lack of memory that showed them to be arrogant and dismissive.

But the report stressed that none of them had been proven in court to be the killers - and that "no fresh evidence" was likely to emerge.

It is one of the most significant achievements of modern criminal forensic science that fresh evidence has, more than a decade later, convicted Dobson and Norris.

Metropolitan Police Acting Deputy Commissioner Cressida Dick, who ordered the cold case review, said: "We currently have no live lines of inquiry. We do of course acknowledge that there are five people we believe involved in that murder. We have not brought all those people to justice.

"Were we to have new information or new evidence we would respond to that."