Stephen Lawrence: The legacy

- Published

- comments

Lawrence murder took on 'political and social dimension'

The name Stephen Lawrence has come to define a watershed in British cultural life.

His death was not the first nor the last murder of a young black man blamed on racist killers in south London in the early 1990s.

At the time, estates in the area were daubed with graffiti proclaiming "white power", black activists were busy recruiting to anti-racist groups and local police were being accused of not taking the murder and the protection of young black people seriously enough.

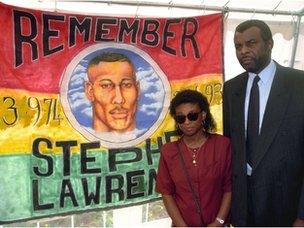

Even so, it is questionable whether the case would have entered the wider public consciousness without the dignity and humanity of two people - Stephen's parents, Neville and Doreen. Nelson Mandela, then leader of the African National Congress, visited the family during a visit to the UK.

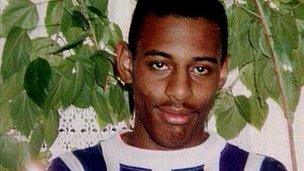

Stephen Lawrence was attacked by a group of white youths in south-east London

The chair of the Equality and Human Rights Council, Trevor Phillips, believes the family's humanity touched the nation.

"For the first time the British public saw parents, a family, whose grief was so patent and whose dignity was so clear, that everybody could identify with them. White Britain realised that, actually, black Britain and black Britons aren't really that different."

The murder became what is known as a "signal crime" - an event which took on a political and social dimension. Former Labour minister Jack Straw says he was determined to seize the opportunity for reform as soon as Labour came to power in 1997.

"The thing that I am proudest of as home secretary was setting up the Lawrence inquiry and that I was able to drive through changes that have had the most significant effect on the British landscape of any of the things that I did."

The inquiry, headed by Sir William Macpherson, was held at Elephant and Castle in South London - a location which suggested a determination to understand what life was like for mixed communities in the inner city.

Doreen and Neville Lawrence in 1995

The attendance as witnesses of five white men who had been suspects in the Lawrence murder saw anger spill over. They were showered with missiles and abuse from a largely black crowd as police escorted them from the inquiry.

However, the subsequent report inquiry pointed its finger, not at suspects, but at the police. It concluded that the Metropolitan Police was "institutionally racist" - that its structures and processes inevitably resulted in racist outcomes.

The finding was greeted with horror by many in Scotland Yard, but it prompted a transformation of the service: its recruitment, training, practices and accountability.

Other legislation went further. The Race Relations Amendment Act 2000 placed a new duty on public bodies to eliminate discrimination and promote racial equality. Diversity and racial awareness became key parts of workforce training in both the public and private sectors.

Professor Peter Saunders, author of The Rise of the Equalities Industry, argues the focus on race has become counter-productive.

"The more that we go on about the problem of institutional racism in our public service institutions, the more it erodes the trust of the public in those institutions," he says. "That is a heavy price to pay. It would be a price worth paying if those institutions were badly flawed but very often it turns out that they are not."

One member of the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry panel, Dr Richard Stone, says the riots last August demonstrate that institutional reform has not gone far enough. "I came out of the inquiry absolutely full of enthusiasm," he says.

"Now it all seems to have dribbled away. The current disparity in stop and search (of black people) is very disappointing indeed and creates a huge amount of anger in black communities. There are also disparities still in the employment of black and Asian officers."

Problems still exist but Britain is much more at ease with its racial diversity than it was two decades ago. And that tolerance, in no small part, is the legacy of a teenage boy: Stephen Lawrence.