Nazi persecution saw Jews flee abroad as servants

- Published

As the Nazis tightened their grip on power in the late 1930s, Jews in Germany and Austria began to fear for their safety. Many fled abroad using well-documented methods such as the Kindertransport. But less well known is the story of thousands of Jewish women who fled to the UK by getting jobs as domestic servants.

When Natalie Huss-Smickler arrived in England in 1938 as a 26-year-old, she found her new job as a domestic servant something of a shock compared with her secretarial work back home in Vienna.

"My first job in England was very, very hard," she says. "I had to work from 8am to 11pm with an hour's break, cleaning and scrubbing and looking after the house, with half a day off a week.

"After a few weeks I complained, saying it's a bit too hard. The lady of the house said, 'If it's too much for you, I'll send you back to Hitler.'"

Natalie was one of an estimated 20,000 Germans and Austrians, mostly women, to take advantage of the domestic service visas being issued by the British government in the late 1930s. The women, predominantly Jewish, took the work to escape from the Nazis.

This number means domestic service visas were hugely significant in saving Jews, about double the number saved by the celebrated Kindertransport - but their story has largely been forgotten.

The holder of a domestic service visa had a priceless ticket to get out of the Nazis' reach - even if it did mean that many middle-class women, who may even have had servants in their own households, were cooking, cleaning, making beds and scrubbing floors for the first time in their lives.

Natalie almost fell into the Nazis' clutches before she arrived in England.

She was on a train in September 1938, bound for a ferry to England, when it was stopped at a Belgian border station. An announcement was made over the loudspeaker that all Jews should disembark.

With a heavy heart, Natalie reached for her small suitcase. But what she did not reckon on was a group of nuns, in whose carriage she was sitting.

Natalie Huss-Smickler's first servant job saw her work 15-hour days, with only half a day off a week

"The nun next to me put her arm round me and said, 'Sit down. You're not going out,'" Natalie says. "I said 'I'm Jewish.' The nun said, 'You're one of us. Sit down,' and she pressed me down."

So the young Jewish girl sat with the Catholic nuns, nervously awaiting her fate as Jewish men, women and children poured off the train and were lined up on the station platform, bound for concentration camps.

What happened next became an unforgettable moment in Natalie's life.

"There came an inspection. A big SS man looked into the window at me and my heart was in my knees. He saw me with the nuns, gave me a nice smile, winked and walked on. I was saved. I was probably the only Jew to get through."

Once safely in England, she headed to London and her new home in Kensington, where she worked in a doctor's family house. She was grateful to be there - "having a domestic service visa saved my life" - but she felt her employers looked down on her.

"It was a large family all living together, including several brothers. The men didn't look at me, they didn't speak to me.

"I was allowed to sit at table, but if one of the children wanted something I was ordered to go fetch it. It's still in my ears, the voice - 'Natalie, fetch me a glass of water.' It made me feel very humble."

Unhappy with the work and conditions, she left that job, taking up a series of other domestic roles including working as a nanny, continuing to work after the war broke out.

When the fighting ended, she decided to stay in the UK and has lived here ever since. She is now 99 and lives in London.

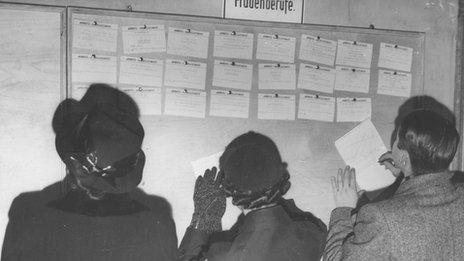

German and Austrian women found servant vacancies posted at the Jewish Refugees Committee offices in London's Woburn House in the late 1930s

Edith Argy, 92, lived in Vienna and came to England one month before her 19th birthday in October 1938.

Edith says that she had "not so much as held a broom" before arriving on England's shores, hired as someone who could clean and maintain a house.

"When I knew I would be a domestic servant overseas, I did a crash course in Vienna to learn domestic skills.

"I totally hated domestic work. Although my family were poor I had never done any at all, because my father spoiled me."

Her first role was at a headmaster's household in Portsmouth. Although she says the family treated her kindly, she hated her new life, hated the food and felt cold, even when she was in bed.

She felt so unhappy that she made a half-hearted attempt to gas herself in the oven.

"I just didn't want to live. I felt I couldn't take being there on my own as a domestic. I honestly don't know if I was trying to do it or if I was hoping I'd be found. I was really desperate."

She recovered and quickly left the household to take on a number of other domestic jobs, but remained unhappy.

Eventually the war ended and she left Britain for a time, working for the American army as a translator in Germany. She later met her future husband, an Egyptian, when in Australia and eventually they settled back in London.

Anthony Grenville, of the Association of Jewish Refugees, says the women who came over using the domestic service visas were mostly from well-to-do Viennese families and "completely unprepared psychologically" for their new lives.

"The British government brought in a visa requirement for refugees seeking entry from Germany and Austria after the annexation of Austria to the Third Reich in March 1938.

"This was a way of the government controlling the sheer weight of numbers of applicants flooding over from the continent, particularly Austrian Jews for whom the situation had become desperate.

Edith Argy is grateful for having been given a servant's job in England, but hated having to carry out domestic work

"Although they took them in great numbers, there was a very clear motive for the British having Jews over - not to save them, but to provide labour for middle and upper middle-class households. A small number of Jewish men also came as butlers or gardeners."

Grenville says that while some were well treated by the families they served, "that was probably an exception", adding that many of the women faced such challenges as not being able to speak English, being given unfamiliar food and enduring a worse quality of living standard than they had enjoyed before.

The Wiener Library in London's Russell Square holds documents relating to domestic service visas, including a pamphlet called Maid and Mistress, issued to those coming over to serve from abroad and also the female heads of the English houses.

This particular document contains the memorable line, aimed at the servants: "English houses are often colder than continental ones and you must expect to guard against the cold by wearing thick underclothes and woollen indoor coats."

This advice would have been little comfort to the young women who were far away from home, doing jobs that made many of them unhappy - but they knew that becoming a servant for an English family had saved their lives.

- Published1 December 2011