Could Murdoch's bold Sunday tabloid move pay off?

- Published

2.7 million buy the Sun on a week day but will they pick up one on Sunday too?

Rupert Murdoch has always relished bravura gestures. Just when you think he is on the back foot, he manages to come out fighting.

He was the man who more or less invented the modern tabloid when he bought and relaunched the Sun in 1969, broke the power of the print unions in Fleet Street by setting up a brand new printing plant at Wapping, and brought multichannel pay-TV to Britain with the launch of Sky.

The past eight months have been dreadful for him and his company: the phone-hacking scandal at the News of the World led to its closure and the collapse of an attempt to take full control of Sky.

An internal investigation into alleged corrupt payments to police led to the arrest of 10 former and current Sun journalists: there were widespread mutterings among the paper's other journalists that they were being hung out to dry in order to protect the parent company News Corporation against possible action by authorities in the US.

But in confirming that he is planning to launch a Sunday edition of the Sun he has managed to restore some of his journalists' battered morale and demonstrate his own largely emotional commitment to newspapers in general and the Sun in particular.

There had been talk of the Sun on Sunday ever since the closure of the News of the World, and a team of journalists had been preparing dummy issues in secret.

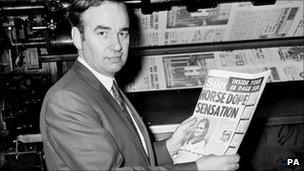

Rupert Murdoch holds one of the first copies of the Sun after he took it over in 1969

After the arrests, it was widely believed those plans had been put on hold indefinitely; now News Corp's chairman has revived them.

It is a typically bold Murdoch move. But it is unlikely to have the wholehearted support of Rupert Murdoch's colleagues on the News Corp board.

Even his son James, who ran the UK newspapers until recently, is said to have doubts.

The corporate disenchantment with the UK newspaper business is partly a result of the phone-hacking scandal, and partly a reflection of how badly all newspapers are doing in competition with digital media.

Most newspapers' circulations are in steep, long-term decline, down year-on-year by anything from 5% to 30%.

The exceptions are the News of the World's erstwhile rivals among the Sunday tabloids.

Two-thirds of the defunct paper's 2.7 million buyers switched immediately to rival titles, and those papers' sales in many cases are still much higher than they used to be.

Celebrity scandals

The Daily Star Sunday, for instance, sold an average of 685,000 copies in the last six months, double what it sold a year earlier; and the Sunday Mirror's sales are up from 1.1 million to 1.8 million.

But many of those who tried other titles in the immediate aftermath of the News of the World's closure have since stopped buying a Sunday paper entirely.

How many could a Sun on Sunday lure back? Or have they been lost to the newspaper market entirely, like so many others? How many of the Sun's 2.7 million weekday buyers - many of whom must buy it on the way to work - can be persuaded to read it seven days a week?

And what kind of editorial formula would work best? A News of the World in all but name, majoring on celebrity scandals and hard-nosed investigations? Or a paper - which might be cheaper to run because it requires fewer dedicated staff - that bears a closer resemblance to the daily Sun?

News International's internal market research may offer some answers to questions like these. Or the team at Wapping may be travelling blind, and relying on instinct and experience to guide them.

But then, one of the things Rupert Murdoch has always liked about the newspaper business is the excitement that comes from having to make quick judgements on the basis of little more than a hunch.

- Published17 February 2012

- Published17 February 2012

- Published11 February 2012

- Published9 July 2013