Church 'does not own marriage'

- Published

- comments

Lynne Featherstone said marriage was "owned by the people"

The Church does not "own" marriage nor have the exclusive right to say who can marry, a government minister has said.

Equalities minister Lynne Featherstone said the government was entitled to introduce same-sex marriages as a "change for the better".

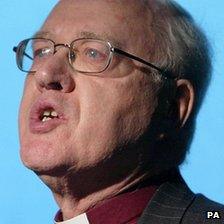

The Liberal Democrat was responding to comments by Lord Carey, a former Archbishop of Canterbury, who said that "not even the Church" owns marriage.

But Lord Carey accused her of putting an "unwarranted slant" on his words.

Ms Featherstone's comments come as ministers prepare to launch a public consultation on legalising gay marriage next month.

Traditionalists want the law on marriage to remain unchanged.

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Ms Featherstone said: "Some believe the government has no right to change it (marriage) at all, external; they want to leave tradition alone.

'Reflect society'

"I want to challenge that view - it is the government's fundamental job to reflect society and to shape the future, not stay silent where it has the power to act and change things for the better."

Her comments came after Lord Carey, a critic of plans to legalise gay marriage, said "not even the Church" owns marriage.

She said: "(Marriage) is owned by neither the state nor the Church, as the former Archbishop Lord Carey rightly said.

"It is owned by the people."

But Lord Carey told the Telegraph: "When I said that not even the Church owns it (marriage), I meant that the Church has no authority to change the definition of marriage as far as Christian thinking is concerned - there is a givenness to it.

"Lynne's logic implies the will of the people is sovereign.

"So let's suppose that in 10 years' time it is proposed that, as people are living in multiples of four, we may call that marriage also."

Ms Featherstone also appealed to people not to "polarise" the debate about same-sex marriages.

'Underlying principles'

"This is not a battle between gay rights and religious beliefs," she said.

"This is about the underlying principles of family, society and personal freedoms."

Lord Carey held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1991 to 2002

Civil partnerships give same-sex couples the right to the same legal treatment across a range of matters as married couples but the law does not allow such unions to be referred to as marriages.

Earlier this month, Lord Carey said legalising gay marriage would be "an act of cultural and theological vandalism".

The Church of England said in December it would not allow its churches to be used for civil partnership ceremonies unless the full General Synod, the Church's governing body, gave consent.

It said it would not host them just as a "gentlemen's outfitter is not required to supply women's clothes".

The announcement came after a new law allowing civil partnership ceremonies to be conducted in places of worship in England and Wales comes into effect.

The Roman Catholic bishops' conference of England and Wales said this month that the government's proposals to create civil partnerships for same-sex couples would "not promote the common good", and that it strongly opposes them.

'No monopoly'

The government will open a consultation on the issue of same-sex marriages - as opposed to civil partnerships - next month. A similar consultation was conducted by the Scottish government last year.

Mike Judge, of the Coalition for Marriage, a campaign group which is against the government's changes, said the Church "does not have the monopoly on marriage" but the government "does not own marriage" either.

"I don't think Lynne Featherstone should be bulldozing ahead with plans to redefine it," he told the BBC News Channel.

He added that it appeared the government's consultation was "just going to be about how we redefine marriage, not whether we redefine marriage".

Ben Summerskill, chief executive of Stonewall, a gay rights charity, said the issue was not about religious freedom, nor was it party political.

"Ultimately it's about the freedom of a small group of people to be treated in exactly the same way as everyone else," he said.

- Published20 February 2012

- Published28 January 2012

- Published27 October 2010