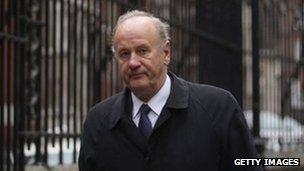

Leveson Inquiry: Lord Condon warns against bureaucracy

- Published

A "massive bureaucratic over-reaction" of police having to record all contact with the media should be avoided, former Met chief Lord Condon has said.

He told the Leveson Inquiry into press standards there had to be clear rules of engagement for the police's dealings with journalists.

Lord Condon was Metropolitan Police Commissioner between 1993 and 2000.

During his time there was a "small but significant" number of officers whose behaviour was "totally unacceptable".

He said this behaviour varied from minor disciplinary issues right the way through to serious criminal matters. He said police regulations were amended in 1999 to deal with "bad officers".

Police leaks to the press were a concern when he was commissioner, he said.

Lord Condon said his relationship with the media would be the single thing dominating his life "for every waking minute I was on duty".

He told Lord Justice Leveson that in the event of a major act of terrorism in London, there would be "an insatiable demand for the commissioner of the day to be saying things about it, to be reassuring the public, to be giving information".

'Grooming process'

Lord Condon said policing was intensely political but in his view the commissioner must be without any favourites in the media and must treat the press without fear or favour.

He told the inquiry that he tried to meet every newspaper, TV and radio editor once a year to explain the work he was doing at the Met.

He said his preference was to have meetings with editors on police premises but occasionally would meet them at their office or in restaurants.

Lord Stevens said it was important for there to be relations between the police and press

Lord Condon said he introduced a code of practice for acceptance of gifts and hospitality in 1997.

He told the inquiry that accepting hospitality could be the start of a "grooming process" which leads to "inappropriate and unethical behaviour".

"In any walk of life, hospitality can be appropriate, can be sensible, can be necessary, can be ethical," he said.

"But on the other side of that, it can lead to inappropriate closeness, and in some cases that can lead to criminal behaviour."

Lord Stevens, Met Commissioner between 2000 and 2005, then told the inquiry that he oversaw a major anti-corruption initiative as deputy commissioner at the Met from 1998.

He told the hearing that he did not like off-the-record police briefings to journalists, especially if officers were giving their opinion.

Lord Stevens said he was absolutely determined not to favour any one newspaper group when he was at the Met.

'Right reasons'

Asked about the force's inquiry into phone hacking, after he had left, he said he found it "difficult to criticise" but added he hoped as commissioner he would have been "quite ruthless" in pursuing the allegations.

Lord Stevens had his autobiography serialised in the News of the World and wrote columns at £7,000 per article, a contract he terminated in October 2007 over concerns about the phone-hacking convictions.

"I would never have written the articles if I had known what I now know," he said.

He said it was important for there to be relations between the police and press "for the right reasons", such as investigative journalism.

Lord Stevens also accused former home secretary David Blunkett of briefing the media against him.

He said: "Every now and again I was seeing headlines saying he was going to sack me and things like that, which of course had never been said to my face. I found that quite difficult, especially as we were getting superb results."

Mr Blunkett later responded saying he was familiar with Mr Stephen's recollections, but his briefings had been public, for example when he stated that he wanted the Met to reverse a 50% increase in street robbery.

Lynne Owens, chief constable of Surrey Police, formerly of the Met, told the inquiry she did not want to risk meeting press in a social setting, which journalists found "slightly strange".

Responding to Robert Jay QC's comment that this was an "extremely austere approach," she said it was "entirely appropriate".