Antarctic mission: Who was Captain Lawrence Oates?

- Published

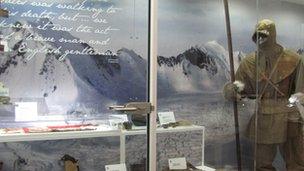

All five men who took part in the final leg of the journey to reach the south pole died on the difficult journey back to base (Picture: PA/University of Cambridge)

"I am just going outside and may be some time." With these words, Antarctic explorer Capt Lawrence Oates set out to meet his death 100 years ago, aged 31, and entered the history books.

He was one of five men who died as they tried to return home from Robert Falcon Scott's ill-fated expedition to the South Pole in 1912.

Capt Oates is remembered because of his act of self-sacrifice, committed because he believed he was slowing the others down.

Now the Oates Gallery - an exhibition in Selborne, Hampshire, which opens on Saturday - tries to reveal the man behind those famous last words.

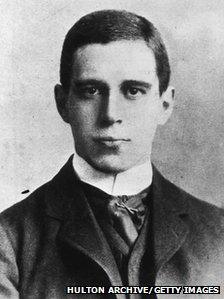

Lawrence "Titus" Oates was born into a wealthy family (Picture: Capt Oates's family)

As the exhibition prepared for opening day, the second floor of 18th Century naturalist Gilbert White's home in the quiet Hampshire village was a hive of activity.

A stuffed King Penguin watched over the curators passionately discussing how best to pay tribute to Capt Oates.

The whole floor is dedicated to the Putney-born adventurer - pictures of his childhood and then his military days combine with images taken by Herbert Ponting on the Antarctic mission a century ago.

Maj Gen Patrick Cordingley, who co-wrote a biography of Capt Oates, carefully ensured the adventurer's shoes - among the few items salvageable from the frozen tent where the others' bodies were found - were displayed in a prominent position.

He said Capt Oates, whose body was never found, was "an ordinary man who was made extraordinary by the circumstances he faced at the end of his life".

Capt Oates was born into a moneyed family, yet he is said to have had a self-effacing demeanour which made him popular with most of those he met.

He was unable to pass the necessary exams to join the Army and instead joined a militia regiment. But later, to his immense delight, he was given an attachment to the British army's 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons.

In March 1901 during the Boer War in South Africa, he refused to back down in the face of an ambush. Instead, he sent out the message: "We came here to fight, not to surrender."

Although the Boers were repulsed, an enemy bullet shattered Capt Oates's thigh, leaving him with a limp and one leg shorter than the other. This injury would cause him further pain towards the end of his life, when the chill of the Antarctic intensified the effect of his injuries.

'Wretched crocks'

Yet his war wounds did not deter him from leading an active life. While in India in 1909, his love of hunting - one of his favourite pursuits along with racing and boxing - resulted in him taking an unusual step.

He was so unimpressed with the foxhounds he found in the country, he got his brother to send out a fresh pack of dogs from England so he could hunt to the standard he desired.

The gallery takes up the second floor of 18th Century naturalist Gilbert White's home

And when Capt Scott advertised for crew for his scientific expedition, the soldier raised the funds needed to secure a place on the team.

He just needed to tell his mother, who reportedly controlled the family estate, and make sure he got the necessary permissions from the War Office.

He signed up to be a midshipman on the Terra Nova - the ship taking the men to their destination - but Capt Scott did not send him to Siberia to get the ponies required for the expedition, despite this being his area of expertise.

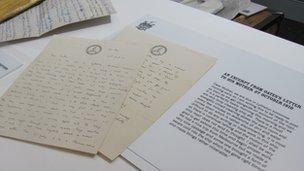

This was a source of irritation to Capt Oates, and in a letter sent at the start of the endeavour, he wrote that the £5 ponies which had been bought and shipped over were "very old for this sort of job" and described them as "a wretched load of crocks".

But in a letter to Mrs Oates in October 1911, Capt Scott acknowledged that her son had played an integral role on the team by caring for the beasts.

"I really don't know what our party of sailor and scientific men would have done without him. Everything depends on the successful work of these animals and your son kindly took charge of them," he wrote.

Capt Lawrence Oates was always seeking his next adventure

Capt Oates's great-nephew Bryan - who lent many of the documents on show in the exhibition - said that his great-uncle had a mutual respect for Capt Scott, although they did not agree on every aspect of the organisation of the trip.

Mr Oates said: "He came from such a secure background that he did not feel that he had to kowtow to anyone - yet he would obey orders implicitly."

'The poor soldier'

Capt Scott sought sponsorship and publicity for the expedition - at least before Norwegian Roald Amundsen decided he would also compete for the crown of being the first one to conquer the south pole.

In a letter Capt Oates wrote to his mother in 1910, his distaste for this showmanship was clear: "I must say we have made far too much noise about ourselves, all the photographing, cheering, steaming through the fleet etc etc is rot, and if we fail will only make us look more foolish."

In another letter to his mother, dated 28 October 1911, he voiced the thought of returning home, but added he did not want to "spoil" his chances of being on the final leg of the journey as "the regiment and perhaps the whole Army would be pleased if I was at the pole".

But the men struggled to reach the point where they believed the south pole was. It became more apparent that the ponies chosen were not fit for the job - proving Capt Oates right.

And Capt Oates noted he was facing constant trouble with his wet feet as the party travelled along the hardened ice.

When the men eventually came across the remnants of the Norwegian expedition's camp, a sombre mood came over them. They had lost.

Capt Oates kept up a regular correspondence with his mother Caroline

But Capt Oates commended Amundsen's team: "I must say that man must have had his head screwed on right. The gear they left was in excellent order and they seem to have had a comfortable trip with their dog teams, very different from our wretched man-hauling."

The men began their difficult journey back but the freezing conditions led to Capt Oates's big toe turning black and his body turning an unhealthy yellow colour.

Maj Gen Cordingley said: "His feet had been giving him trouble for two months but he had hidden his problem from the others. Now this was no longer possible."

Capt Scott wrote in his diary: "If we were all fit I should have hopes of getting through, but the poor soldier has become a terrible hindrance, thought he does his utmost and suffers much I fear."

Explorers knew the risks, that there would be no evacuation in cases of serious illness or injury. As team member Apsley Cherry-Garrard wrote in his account of the expedition: "There is no chance of a 'cushy' wound. If you break your leg on the Beardmore (glacier), you must consider the most expedient way of committing suicide, both for your own sake and that of your companions."

On 15 March, Captain Oates suggested that the remaining explorers should leave him in his sleeping bag, but they refused.

But the man they affectionately called "the soldier" knew the end was near and, it seemed, had had enough.

He awoke on 16 March 1912 and, leaving his shoes behind, walked out into the storm blowing outside.

"He went into the blizzard and we have not seen him since," Capt Scott recorded in his diary the next day.

In her grief, Capt Oates's mother Caroline had ordered the destruction of the diaries of her "baby boy", but her daughter Violet transcribed many of the documents so they were not lost to history.

Maj Gen Cordingley said: "His final words are typical. It was his way of saying goodbye but without drawing too much attention to what he was actually doing. He died so they could have a chance of living.

"That was simply the sort of man he was."

- Published2 November 2011

- Published17 January 2012

- Published17 January 2012