Researchers praise Scott's South Pole scientific legacy

- Published

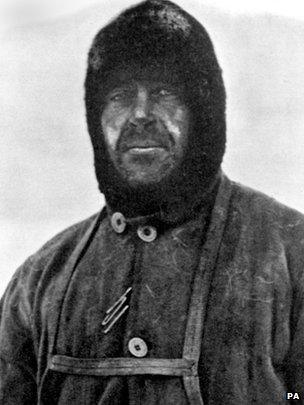

If Scott had not been a Naval man he would have been a scientist

Researchers, explorers and relatives have praised the contribution Captain Robert Falcon Scott made to science.

The tributes come on the centenary of Scott's party reaching the South Pole.

The so-called Terra Nova expedition found that they had been beaten to the pole by a Norwegian team by 33 days, and on their return journey Scott and his four fellow explorers died.

Some saw it as a mission of heroic failure, and Scott quickly became an iconic figure for his efforts.

But in the later half of the 20th Century his status was re-examined by historians, some of whom questioned Scott's capabilities and contribution.

Scott's granddaughter Dafila Scott told BBC News that it was time to re-evaluate his life and contribution.

"My grandfather's reputation has been through various ups and downs and this is a good time to reflect on the wider legacy and what they achieved not only in getting to the pole but the scientific work that they did," she said.

Ms Scott is a zoologist by training, but subsequently went on to become a painter and artist. She says that she is not surprised her grandfather became interested in science.

"There's no question that he was very much focused on the science," she said.

"The exploration was part of it but it was only part of it. In the Antarctic, there were and still are so many possibilities for things to discover. It's a wonderful place. It's an open air laboratory".

It is a view shared by Scott's grandson, Falcon, who has recently arrived at the Antarctic as part of a project by the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust to restore the hut that was the base of operations on the North Shore of Cape Evans on Antarctica's Ross Island.

Speaking from Scott Base he told BBC News: "It's long overdue that his scientific legacy should be appreciated. It was a very significant part of the expedition. They undertook the science in very extreme conditions with amazing endurance.

"You only realise that when you come down here. There was no contact with the outside world and the risks were enormous."

On his arrival at Scott Base two weeks ago, Falcon Scott went into his grandfather's hut alone so that he could fully take in the moment.

"It was like walking back in time," he said.

"There's a feeling of the presence of the man. There are still his possessions lying there, lots of tins of food that are well preserved and clothing on the beds. It was like the man had only just left it".

According to Heather Lane, curator and keeper of collections at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, the aim of the Terra Nova expedition was not just to get to the pole but also to do as much scientific investigation as possible.

"When Scott found out about the Norwegian team's plans to get to the pole first he makes a very clear decision to stick with the scientific programme," she said.

She said there was "enormous disappointment" in getting there second, but "he felt it was so important that they stick to the idea of the mapping and the science and the collection of the meteorological data all the way to the pole, and it was that that was going to be the long term legacy".

Elin Simonson from the Natural History Museum shows artefacts from the Scott expedition to the South Pole

There were 12 researchers on the expedition who were recruited by Scott himself. One member of his team, Charles Wright, wrote that "if Scott had not been a Naval man he would have been a scientist".

That is a view shared by the British adventurer and Scott biographer Sir Ranulph Fiennes, who himself has crossed the Antarctic continent.

"He was a curious man, he was a very clever man. He was a brilliant man in every respect and he was the world's greatest polar explorer," Sir Ranulph told BBC News.

The Terra Nova expedition was Scott's second excursion to the Antarctic. It was more ambitious in scope and its scientific aspirations than Scott's first trip on the Discovery expedition 10 years earlier.

In his expedition prospectus, Scott wrote that Terra Nova's principal objective was "to reach the South Pole, and to secure for the British Empire the glory of this achievement".

Of course, a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen reached the pole first. And Scott and his team never returned home, dying of starvation and exposure on the return journey.

But alongside their bodies were several pounds of their precious geological samples and scientific notebooks which, even while approaching death through exhaustion, Scott and his men continued to take with them.

Those samples and data are an enduring legacy of the Terra Nova expedition.

The expedition was the ambitious scientific endeavour of its time, and it was the largest ever research mission to the pole - comprising 12 scientists including two biologists, three geologists and a meteorologist.

The team collected specimens from 2,109 different animals. Of these, 401 were new to science. They also collected rock samples, penguin eggs and plant fossils.

The expedition collected specimens from thousands of different animals

One of the most important discoveries was a fossilised fern-like plant which was known to grow in India, Africa, New Zealand and Australia. It suggested that the climate 250 million years ago had been mild enough for trees to grow.

More intriguingly, the discovery, along with other evidence gathered by Scott's team, was a hint that India, Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Antarctica had in the distant past all been part of one "supercontinent". Researchers now call this landmass Gondwanaland.

It was around this time that the idea of continental drift was first put forward, independently, by the German scientist, Alfred Wegener. Scott's team also collected the first thorough set of weather data for the Antarctic, which has served as a baseline to track changes in weather patterns ever since.

The team also travelled for five weeks to study an Emperor penguin colony come on to land and lay their eggs. The team took some of the eggs - which contained embryos - believing that they would shed more light on a possible link between birds and dinosaurs. According to David Wilson, the great nephew of Scott's chief of scientific staff, Dr Edward Wilson, their efforts illustrated just how passionate they were about the science.

"This was one of the greatest scientific questions of the time. But they had to go through extraordinary hardship to get the penguin eggs. It was minus 60C, so cold that their teeth cracked," he said.

In the end, the eggs were of little use in this regard, but the efforts the men went to and the risks they took under the most extreme circumstances epitomise a spirit of heroic scientific investigation that arguably has not been matched since.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published2 November 2011