Afghanistan Warrior blast: Deaths throw spotlight on UK mission

- Published

Five of those killed served with 3rd Battalion the Yorkshire Regiment

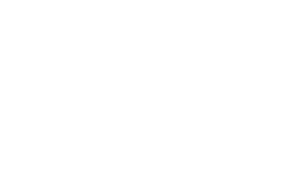

The fatal bombing of six British soldiers in their Warrior armoured vehicle in Afghanistan was a "cowardly attack", Defence Secretary Phillip Hammond has said. He also said it would not shake the UK's resolve to complete its mission.

That may be true, but this tragic incident will once again raise the questions about why British troops are still fighting and dying in Helmand, and how much longer they will be there.

The deaths of the six soldiers is the largest loss of life for UK combat forces in a single incident, since the war began.

It also takes the total number of British service personnel who have died in Afghanistan since 2001 beyond the 400 mark. All reasons to take stock and ask whether their sacrifice has been worthwhile?

There are some who will also voice concerns about whether British troops have the right equipment to carry out their job.

Already some are asking if the Warrior gave those six soldiers enough protection? Why, for example, did the government recently announce a £1bn upgrade to the armoured vehicle?

The Warrior in the explosion did not have the V-shaped hull fitted on more modern vehicles - designed to withstand a blast directly underneath.

That said it is still heavily protected and the Ministry of Defence insists the deaths have nothing to do with deficiencies in its armour. More importantly soldiers and military commanders are not blaming the kit.

Exit plan

No vehicle can be designed to withstand the blast from every roadside bomb.

Warriors have survived an IED strike in the past. This though seems to have been a massive explosion. What's more there's a suggestion that the impact may have triggered munitions inside the Warrior to ignite.

It may prove harder for the government to argue that their sacrifice has not been in vain. The reasons though for "being there" have not really changed.

Expressing his extreme sadness at the loss of life in the House of Commons, PM David Cameron also repeated the familiar refrain, from both this government and the last, that British troops are in Afghanistan for the UK's own national security.

Perhaps that motive has become clouded by the international communities' efforts to help rebuild a nation.

But those in power have always claimed that is not the primary reason for military intervention. The former Defence Secretary, Liam Fox, once stated that Britain was not in Afghanistan to repair a "broken 13th-century country".

A rather blunt, even crude, assessment for which he was widely criticised. But it did at least spell out that the purpose of the military mission was as much about self interest as altruism.

Many will still debate whether the military intervention in Afghanistan is helping to make Britain's streets safer.

Many have argued that it is fuelling extremism in both Afghanistan and beyond, rather than defeating the scourge of international terrorism.

The reality is that the threat from a home grown insurgency - in Afghanistan and neighbouring Pakistan - is now much greater than the weakened influence of foreign al-Qaeda fighters.

Clear strategy

In the end though such arguments may appear academic. More salient is the fact that the international community is now looking for an exit.

By setting a deadline for the end of combat operations - December 2014 - the prime minister has taken some of the heat out of the debate.

If these latest deaths had occurred without such a timeline, then the demands for a hasty withdrawal would have been even louder.

There is now a clear strategy to hand over responsibility to the Afghans. Western politicians are locked into a timetable that will see the whole country transition to Afghan control over the next few years - a process that is already well under way.

There seems to be little now that can shift them dramatically off that course. Even the recent violent unrest caused by US soldiers burning the Koran, and the subsequent murder of Americans in uniform by Afghans in uniform, has not halted the transition process.

Though it has shaken trust and confidence.

In the end, such attacks - and tragedies like the deaths of those six British soldiers - can only influence the speed and scale of the withdrawal.

The recent murder of French soldiers - again by rogue members of the Afghan Security Forces - did prompt President Nicholas Sarkozy to bring forward his nation's timetable for withdrawal.

Though the decision may have also been influenced by his own election back home.

Politicians in both Washington and London have still not spelt out their own plans for withdrawing combat troops. How many and by when?

Whether international forces will leave a lasting legacy, and in answer to the question as to whether the sacrifice has been worthwhile, it is now largely in the Afghans own hands.

All nations involved, led by the United States and Britain, agree that ultimately there needs to be a political solution to end the decades of tribal, Taliban and regional feuding.

The West has been criticised for not doing more to facilitate those talks, but ultimately it is not something that is in their power to resolve.