Televising trials: What can be learned from US?

- Published

- comments

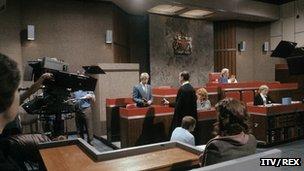

Coverage of the courts will be nothing like Crown Court, the 1970s TV drama

Television cameras are to be allowed to film courts in England and Wales for the first time, it has been announced in the Queen's Speech. What can be learned from the experience in the United States and Scotland?

In the 1970s, a staple of daytime television was the drama serial Crown Court.

In half-an-hour episodes - including a break for adverts - an entire criminal trial in the fictional town of Fulchester was covered, with the drama climaxing in a verdict from a jury of ordinary people at the end of the week.

When it was announced in the Queen's Speech that TV cameras would be allowed in English and Welsh courts for the first time, many people might have imagined something as gripping and dramatic as Crown Court.

But the reality is likely to be very different and a long way from US-style televised trials.

One of Britain's top prosecutors, Brian Altman QC, said the broadcast of US trials such as OJ Simpson and Michael Jackson had had the effect of "sensationalising the proceedings".

But Mr Altman, who prosecutes many high-profile cases at the Old Bailey, said the British system was very different and was not likely to end up in the "free-for-all" seen in US trials.

"One has to understand the process in America against a background of complete almost unfettered freedom and discretion," he said.

The first cameras will be filming only in the Court of Appeal.

Lord Bracadale: ''You lost your temper and murdered her in a sustained attack''

Later they are expected to be allowed into courts such as the Old Bailey, but will be limited to filming only the judge delivering his sentencing remarks.

Nick Catliff, managing director of independent production company Lion Television, and who in 1994 persuaded a Scottish judge to allow a TV crew to film an armed robbery trial in the sheriff court, said the latest move was a "foot in the door".

"But you won't get the the drama of a verdict," he said.

Unlike south of the border, filming in Scottish courts is entirely up to the discretion of the trial judge.

Last month another judge, Lord Bracadale, <itemMeta>news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-17754517</itemMeta> for the murder of a woman after she broke off their affair. It was the first time cameras had broadcast live from a Scottish court.

Filming and broadcasting in English and Welsh courts are currently banned under Section 41 of the Criminal Justice Act 1925 and Section 9 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981.

The Ministry of Justice said recently that justice must be done and "be seen to be done", and said the government and judiciary was determined to improve transparency and public understanding of courts.

Mr Altman welcomed the idea of TV cameras in court as an important means of educating the public about what actually goes on inside the courtroom.

But he added: "I do have an issue with filming certain witnesses' testimony".

Expert witnesses and police officers may be able to withstand the pressure of their performance being broadcast, he said, but "fearful or intimidated witnesses would refuse to attend court, which could impact seriously if not terminally on the successful prosecution of a case".

In February three of the UK's biggest news providers - BBC, ITN and Sky - wrote to the prime minister urging him to introduce new legislation to allow TV cameras as soon as possible.

They said: "For too long the UK has lagged behind much of the rest of the world on open justice. The time has come for us to catch up."

But some have reservations about TV cameras in court.

A Victim Support spokesman said: "The justice system does need to be more transparent and accessible.

"But this does not mean that court cases should become a new form of reality TV.

"Any move towards an increased role for the media needs safeguards to protect victims and witnesses."

The civil rights pressure group Liberty also said it did not have issues with the filming of sentences being handed down, but would have concerns over any moves to extend filming further and into trials themselves.

A spokesman said the proposal seemed a plausible way of increasing public understanding and trust in the sentencing system.

"But fair trials are not trials by media, and talent shows and text voting are no substitute for justice."

Many lawyers and civil rights campaigners often refer negatively to US cases like the trial of OJ Simpson in 1994, saying the trial became a media circus.

The trial of Anders Behring Breivik of Norway has also been held up by some as the downside of televising justice.

But <link> <caption>Simon Bucks, associate editor of Sky News, argued recently in the Huffington Post:</caption> <url href="http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/simon-bucks/cameras-court-breivik-a-tale-of-two-televised-c_b_1434406.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> "For Norway, the television coverage of this trial is clearly part of a national catharsis. Norwegians need to understand why Breivik did what he did."

Some critics claim the televising of the Breivik trial gave his extremist views too much of a platform

Bill Sheaffer, an attorney in Florida, said televising the criminal justice system in the US had been a good thing.

He said: "Since the early 1990s, all 50 states have some form of cameras in court. But there are very rarely any problems. Cameras are stationary and unobtrusive and things are unfolding at a fairly clipped place."

Jurors, children and certain other witnesses - like rape victims or police informants - could not be filmed and mistakes were very rare, he said.

Mr Sheaffer, who works as a legal analyst for the TV station Channel 9, said: "The fear that cameras are going to alter the ability of a defendant to get a fair trial have proved unwarranted. But it's certainly wise for you in Britain to make this change gradually."

Mr Catliff says British trials will never be televised to the same extent they are in the US.

In America, he said, there was "no sense" of sub-judice - the concept that comments should be restricted while a case is being considered by a court, to avoid prejudicing it.

"They have huge speculation before and during trials, but we can't do that in this country because of the Contempt of Court Act," he said.

Mr Sheaffer said: "Freedom of the press is just one of the cornerstones of American democracy, and if the courts are going to err between the rights of the individual and freedom of the press they will go for the latter."

Bill Sheaffer, being interviewed during the Casey Anthony trial last year

He says those who fear televising courts harm a person's chance of a fair trial should take a look at the case of Casey Anthony in Florida last year.

Despite three years of mostly negative press coverage and <link> <firstCreated>2011-07-05T10:50:31+00:00</firstCreated> <lastUpdated>2011-07-05T18:50:51+00:00</lastUpdated> <caption>after a televised trial which gripped America</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-13986356" platform="highweb"/> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/magazine-13986356" platform="enhancedmobile"/> </link> , Anthony was acquitted, much to the surprise of onlookers, of murdering her two-year-old daughter Caylee.

Mr Sheaffer said: "Did the system not work and was she not acquitted?

"The verdict was easier to understand if you followed the gavel-to-gavel coverage rather than if the press had just covered the more sensational aspects of the trial."

Mr Sheaffer also believes televised trials can benefit society.

Last month, neighbourhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman was charged with the second-degree murder of Trayvon Martin, a black teenager whose death has stirred up racial tensions in Florida.

Mr Sheaffer says: "In the Zimmerman case you are going to have a very speedy trial and it's going to be very public and out in the open with greater transparency, so that no matter how it comes out no-one will be able to say there was some type of conspiracy."

- Published18 April 2012

- Published6 February 2012

- Published6 September 2011