Child poverty down as household income drops

- Published

- comments

BBC Radio 5 live spoke to a mother living below the poverty line

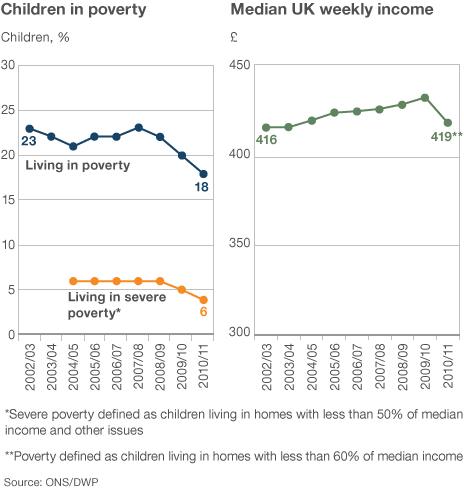

The number of children living in poverty in the UK fell by 300,000 last year as household incomes dropped, official figures have revealed.

In 2010-11, 18% of children (2.3 million) lived in households classed as below the poverty line - a 2% drop.

This was because the measure is based on median incomes which also went down.

The Children's Society welcomed "the lowest poverty level since the mid-1980s" but said that may be reversed by "drastic cuts to support and services".

The government, meanwhile, says drug addiction, homelessness and unemployment should be considered as well as income when defining child poverty.

UK income drop

The government's Households Below Average Income statistics define child poverty as children living in homes taking in less than 60% of the median UK income.

The median - the middle figure in a set of numbers - for 2010-2011 was £419 a week, down from £432 the year before.

As a result, the level of household income which defines "in poverty" fell from £259, in 2009-2010, to £251 a week, the following year.

The BBC's Mark Easton said that explained why 300,000 fewer children were classed as living in poverty.

A fall in income throughout society in tough economic times has meant that thousands of families have been lifted above the poverty line without their circumstances changing at all.

The figures show ministers have a long way to go to meet a target set by the previous Labour government - and enshrined in the 2010 Child Poverty Act - to eliminate poverty by 2020.

And they mean a target set by Labour 10 years ago - when 3.4 million were living in poverty - to halve that figure by 2010/2011 was missed by about 600,000.

The Children's Society said that, while action since 2000 had "pulled 1.1 million children out of poverty", current levels were still "a scar on our national conscience".

"It is shameful that over the coming decade this progress is likely to be reversed by the government's drastic cuts to support and services for the country's most vulnerable children and families," chief executive Matthew Reed said.

Save the Children chief executive Justin Forsyth said the government should focus "not on changing definitions but on policies that work, like the living wage, affordable child care and on early education programmes targeted at low-income families".

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation said "breaking the crippling low pay, no pay cycle that keeps so many working families in poverty would be a welcome start".

Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith said the government remained committed to the Child Poverty Act targets but that it was "increasingly clear that poverty is not about income alone".

Speaking at a community centre in London, he said it was "perverse" that "the simplest way of reducing child poverty is to collapse the economy".

He said a consultation later in the year would look at new ways of measuring child poverty taking into account problems like unemployment, family breakdown and addiction.

"Unless we find a way of properly measuring changes to children's life chances, rather than the present measurement of income alone, we risk repeating the failures of the past," he added.

Iain Duncan Smith: "Life change" important in measuring poverty

He said Labour's strategy of putting "vast amounts of money" into benefits to try to push families above the poverty line had failed.

He pledged the government's universal credit - which will replace a series of benefits and tax credits - would pull the "vast majority" of young people out of poverty if at least one parent worked 35 hours a week at the minimum wage. The figure would be 24 hours for a lone parent.

Labour shadow work and pensions secretary Liam Byrne, meanwhile, said: "Behind [Prime Minister David] Cameron's promises we learn today that those parents and their children will now be abandoned and told, 'you are on your own'."

- Published14 June 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published15 February 2015

- Published17 February 2011