What is the UK's optimum population?

- Published

- comments

We learn today that there are almost half a million more people living in England and Wales than official estimates had suggested. We are pretty good at counting babies and corpses, so we must have been under-counting net migration during the past decade.

It is not a wild underestimate - less than 1% of the total population. But the 480,000 individuals of whom the authorities were unaware will fuel arguments about immigration and how we best deal with an ageing population.

Three groups have expanded significantly during the past decade:

the number of people in their 90s has now reached 430,000

there are a million more 20-somethings

the number of under-fives is up 400,000.

Quite a few local authorities will be poring over the figures to see whether they might be able to argue for a bit more cash from the Treasury to deal with the impact of higher numbers.

But the new data will also prompt fierce argument about the overall population level of our islands, as the Office for National Statistics confirms it will revise its population projections in the autumn.

As things stand, the ONS has suggested the UK population will be almost 72 million in 20 years time and 81 million by 2060.

Is the number too high? What is the optimum population for the UK and how would we achieve it?

The pressure group MigrationWatch UK has argued that the government should take whatever steps necessary to ensure numbers stays well below 70 million people. An online petition, external to that effect has achieved the 100,000 signatures necessary to trigger a Commons debate on the idea.

The petition warns that reaching the 70 million mark within 20 years "will have a huge impact both on our quality of life and on our public services".

The Optimum Population Trust, external goes further with proposals that government encourage couples to stop at two children and the introduction of a one-in one-out policy on immigration. "That way our numbers can be allowed to stabilise and reduce gradually to a lower, environmentally sustainable level," the organisation says.

But while there are many who would agree we live on a crowded isle, population control comes at a cost - social and economic.

Only last week the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) pointed out that restricting inward migration would mean either even bigger cuts to public services or hefty tax rises to pay for an ageing population.

In its annual report, external to ministers, it said in the medium term "higher inward migration would tend to increase tax receipts and not add much to age-related spending pressures, even whilst allowing for an increase in GDP from extra employment".

Spending on health, pensions and care costs are set to soar over the next half century and, if the government is committed to ensuring public debt does not exceed 40% of GDP, the squeeze on the working population becomes ever greater.

Assuming a net migration rate of 140,000 a year (still significantly higher than government target of under 100,000 and significantly lower than the current rate of 260,000), the OBR calculates that the additional cost of the elderly would require further spending cuts and tax rises worth £17bn.

Were the UK to maintain its current net migration level, the annual growth rate would increase form 2.4% to 2.7% and the fiscal consolidation required to bring national debt to 40% of GDP would be three times smaller at £4.6bn. (These estimates, of course, were made before Monday's census data was published.)

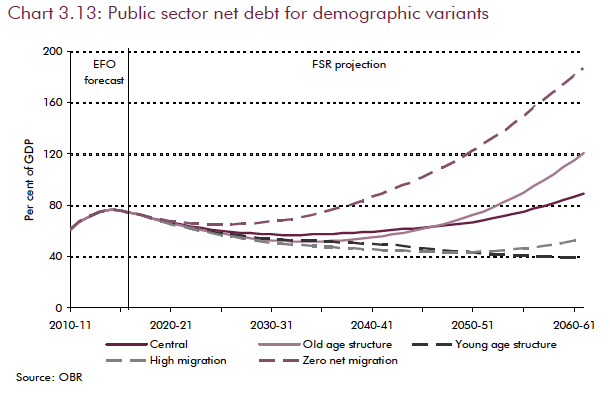

This graph from the OBR report demonstrates how the deficit is affected by different assumptions. The line marked old age structure assumes net migration of 140,000 but with higher life expectancy and lower fertility. Young age structure combines high migration with lower life expectancy and higher fertility.

A high migration policy has a sting it in its tail, of course. Assuming that many of those migrants stay in Britain beyond their working life, it will result in another population bulge hitting retirement in 40 to 50 years time.

Women in Britain are having more babies

As the OBR says, "higher migration could be seen as delaying some of the fiscal challenges of an ageing population rather than a way of avoiding them".

Nevertheless, on the OBR analysis, one can see that policies restricting inward migration of young workers to reduce the population will, in the medium term at least, put far greater pressure on British workers to support the elderly. Immigration will look a lot more attractive if it means fewer cuts and lower taxes.

Equally, the idea that politicians should advise couples how many children they should have would be deeply controversial in Britain. Decisions on childbearing have been seen as a matter for families, not government ministers. In any event, as can be seen from the OBR analysis, there are arguments for and against the UK reducing its fertility rate.

The ONS has been trying to understand what has been driving the big rise in the number of under-fives revealed by the census. As I reported last June, there has been a sudden and unexplained rise in the fertility rate over the past few years.

Although the increase in the number of women of childbearing age is mainly due to migration over the past decade, they still represent only a small proportion of the total and cannot explain the significant rise in total fertility rate.

Britain is living longer, seeing more foreigners arriving and having more babies too. Those three facts are pushing up our population and posing profound questions about the best way forward.

UPDATE 15:20 BST

"No credible evidence has yet been published to show why a UK population of 70 million is preferable to a population limit of 50, 60 or 80million - or any other number," says the Migration Observatory, external think-tank based at Oxford University.

"We cannot base major policy decisions on a finger-in-the-air decision to aim for one round number or another. Policy needs to be based on evidence. At this stage there simply isn't enough to even debate what is at stake."

- Published16 July 2012