Paralympics legacy: Seize the momentum

- Published

Channel 4's Paralympic opening ceremony coverage was watched by a peak audience of 11.2 million

As the London 2012 Paralympics draws to a close, how might all this positive exposure, sporting achievement and discussion around disability affect the future of disabled people?

The Paralympics was in the UK - so immediately grabbed our attention at the end of a phenomenal summer of celebration which started with the Queen's Diamond Jubilee in June.

Some 2.7 million tickets were sold for the Paralympic Games and the amount of media and television coverage was unprecedented.

In the Paralympic Park bubble, if you try to discuss legacy, the main thought is about the sport.

After winning the final track gold medal of the Games in the Olympic Stadium on Saturday night, South African "bladerunner" Oscar Pistorius said he hoped the success of London 2012 would boost the profile of parasport.

'Take responsibility'

But what about those who want to enjoy sport and don't necessarily want to compete at elite level?

Paralympian Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson worries that people will continue to look towards charities to provide expensive sporting equipment, when it's easy to get healthy and sporty without spending thousands of pounds on custom chairs or carbon fibre wheels.

"You can't wait for someone else to do legacy, you've got to take a bit of responsibility for yourself," she says.

"You can go out walking or pushing in your wheelchair - you can go to the local park, you can work out with two tins of beans."

On team sports, she says: "If you can get 10 or 12 people together, to rent a sports hall for two hours is probably £3 or £4 each - for two hours' exercise that's not bad."

Baroness Grey-Thompson says government, schools and the health sector need to "actually talk to each other about what we want these games to bring".

"If we wait for there to be a full legacy programme, we'll have missed the boat really."

Sports Minister Hugh Robertson, meanwhile, has told BBC Radio 5 live the legacy had begun with "confirmed funding for elite Olympic and Paralympic athletes, the range of new facilities, the fantastic list of major sports events coming to this country, a new school games competition which has a compulsory disability element for the first time, a new youth sports strategy and other projects with disability attached."

Disabled people rarely come together in one place due to bad health, accessibility difficulties or just a sense they don't really want to be associated with people similar to themselves - which might serve to further stigmatise them.

If the disparate groups - such as deaf, blind, autistic, wheelchair users, mobility impaired and disfigured - do ever get together, it's usually to fight against issues including benefits cuts.

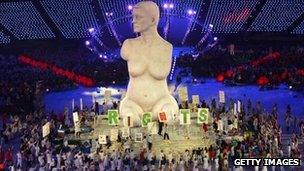

The Paralympics, meanwhile, has been a very visible celebration of disability achievement.

Legacy isn't just one big story though, it's lots of smaller stories.

Stuart Cosgrove, director of creative diversity at Paralympic broadcaster Channel 4, says nearly two-thirds of people questioned in a poll it commissioned said the Games had shifted their attitude towards disability.

He said that, though it was "hard to quantify what that means", comments received by the channel suggested the Games had created an impact "I had never imagined".

"What I am consistently seeing are stories of what appear to be couples who have relatively young children, of ages five or six, with cerebral palsy or who have perhaps had amputations through meningitis.

"The Paralympics for them has not only been inspiring - in the sense of sporting achievement - but they've seen disabilities championed on air and see it as an opportunity for their children to have future engagement in sport, basketball, swimming, and beyond that."

Changed conversations

The interest in the Paralympics is not yet as strong as the Olympics - Channel 4's Paralympic opening ceremony coverage was watched by a peak audience of 11.2 million viewers compared with the 26.9 million who watched the Olympics opening ceremony on BBC One.

But Mr Cosgrove says the higher-income ABC1 audience has been consistent and has shown "the biggest single increase in our audience".

At the beginning of the Games, we were hearing wannabe-positive, slightly uncomfortable-sounding phrases - such as "see the ability not the disability" and "the athletes just want to be taken as seriously as the normal athletes" - from the media.

But the conversations have changed a little since 29 August.

100m gold medallist sprinter Jonnie Peacock was spotted at a "talent ID" event

Comedian Adam Hills' late night irreverent Para-chat show The Last Leg - a title reflecting Adam's lack of a segment of his lower limb - has taken mainstream viewers to dark and delightfully surprising places that only disability humour can go.

And it has given a sense of permission for regular viewers to talk openly about things they may previously have shied away from.

And last Sunday, after Oscar Pistorius claimed his defeat to Brazil's Alan Fonteles Oliveira may have been due, in part, to unfair practices, was the first time we had seen Twitter users passionately discussing the length of a disabled man's artificial leg.

Tim Hollingsworth, head of the British Paralympic Association, has announced that there will be a Paralympic Festival - likely to take place in December - to spot new sporting talent, initially to be held in England.

He notes that it was in a "talent ID" event that 100m gold medallist Jonnie Peacock was spotted.

"It's an incredible journey, it's a fast-moving journey," said Mr Hollingsworth.

"The challenge now is to learn from all the positives that have come out of London and build on the momentum in this country."

- Published7 September 2012

- Published28 August 2012