How the Hillsborough disaster unfolded

- Published

How a crush at a FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest developed, leading to the deaths of 96 football fans.

After two years of inquest evidence, a detailed picture has built up of how an FA Cup match at Sheffield Wednesday's Hillsborough ground turned into a disaster that claimed 96 lives and left hundreds more injured.

The semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest took place on Saturday 15 April, 1989.

The match was sold out, meaning more than 53,000 fans from the two sides would head for Hillsborough for the 15.00 kick-off.

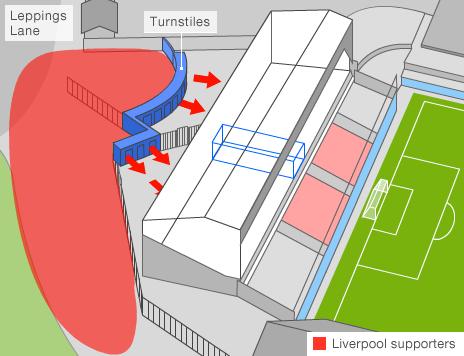

Despite being a far larger club, Liverpool supporters were allocated the smaller end of the stadium, Leppings Lane, so that their route would not bring them into contact with Forest fans arriving from the south.

Football crowds at the time had a reputation for hooliganism and strict segregation was enforced.

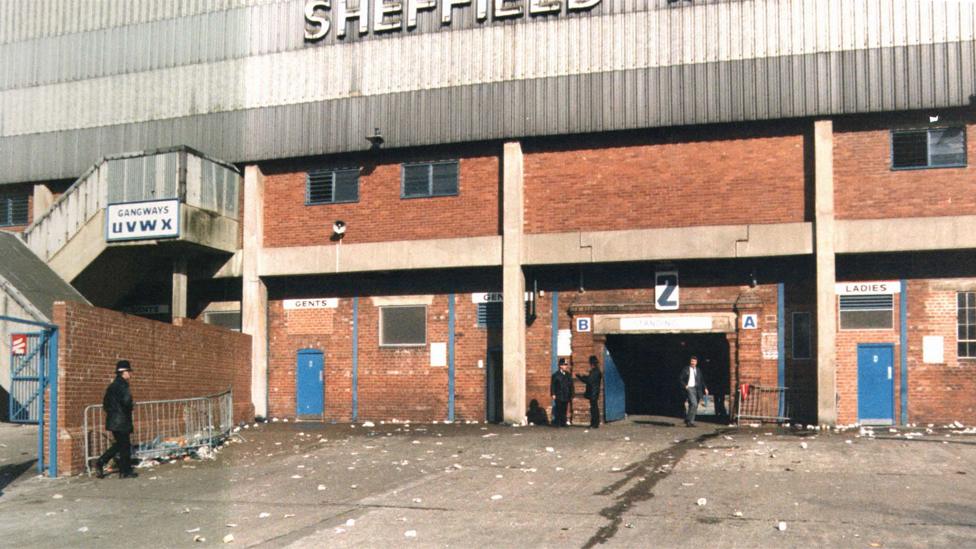

Fans began arriving at Leppings Lane at about midday. The entrance had a limited number of turnstiles, of which just seven were allocated to the 10,100 fans with tickets for the standing terraces.

Once through the turnstiles, supporters would have seen a wide tunnel leading down to the terrace and signposted "Standing".

The tunnel leading to pens 3 and 4 was directly opposite the turnstiles

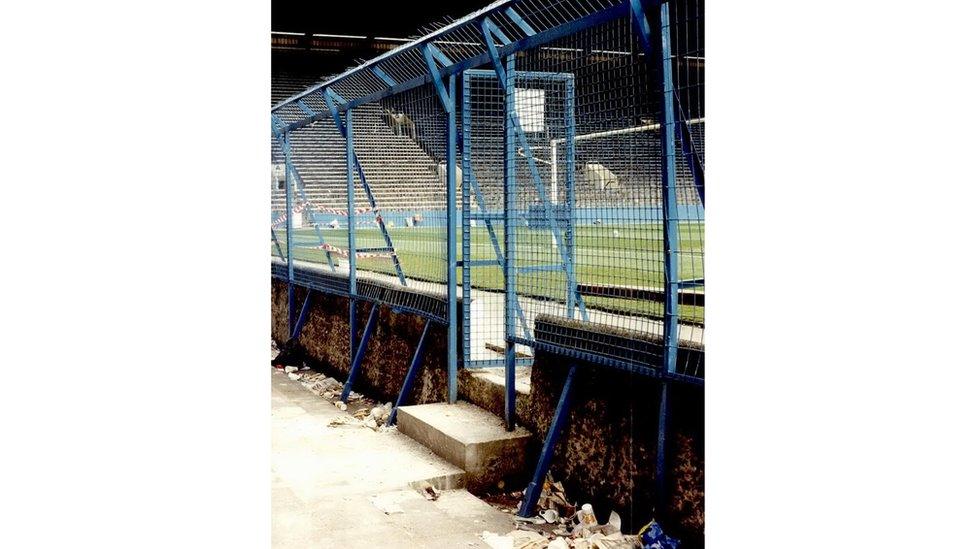

As was common practice in grounds at the time, the terrace was divided into "pens" by high fences that corralled fans into blocks and separated them from the pitch.

The terrace was surrounded by high perimeter fences

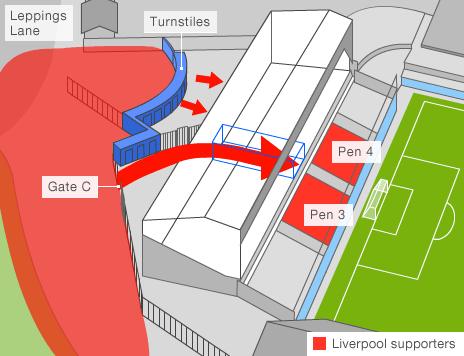

The tunnel led directly into the two pens behind the goal, pens 3 and 4. Access to other pens was poorly-marked - a sign for refreshments was bigger than one showing the way to pens 1 and 2, the inquests heard.

There was no system on the day to ensure fans were evenly distributed across the pens and no way of counting how many were in each pen.

The match commander was Ch Supt David Duckenfield. He was new in his post and had limited experience of policing football matches.

Police expected supporters to "find their own level" by spreading out across the pens in search of space, but this was difficult to do as movement between the pens was by narrow gates at the rear.

Crowd congestion outside

By 14.15 a crowd had started to build outside the Leppings Lane turnstiles and it swelled rapidly over the next quarter of an hour.

Progress through the seven turnstiles was slow and by 14.30 just 4,383 people had entered, meaning 5,700 ticketed fans were set to enter the ground in the half hour before kick-off.

14.15-14.40: Several thousand Liverpool supporters are gathered outside the ground at the Leppings Lane end. As there are only seven turnstiles, admission to the ground is slow

The inquests were told Mr Duckenfield and Supt Bernard Murray discussed delaying the kick off to allow fans to enter but decided against it.

By 14.45 CCTV footage showed there were thousands of people pressing into the turnstiles and alongside a large exit gate, called Gate C.

The funnel-shaped nature of the area meant that the congestion was hard to escape for those at the front. The turnstiles became difficult to operate and people were starting to be crushed.

Gate C is opened

The police officer in charge of the area, Supt Roger Marshall, told the inquests he thought somebody was "going to get killed here" unless the exit gates were opened to alleviate the pressure.

He made several requests and at 14.52, Mr Duckenfield gave the order and the gates were opened.

About 2,000 fans then made their way into the ground. Most of those entering through Gate C headed straight for the tunnel leading directly to pens 3 and 4.

This influx caused severe crushing in the pens. Fans began climbing over side fences into the relatively less packed adjoining pens to escape.

14:52: Police order Gate C - a large exit gate - to be opened to alleviate the crush outside the ground. About 2,000 supporters enter the ground and make for a tunnel leading directly to pens 3 and 4.

The pens' official combined capacity was 2,200. It was later discovered this had not been updated since 1979, despite modifications made to the ground in the intervening decade.

At 14.59, the game kicked off. Fans in the two central pens were pressed up against the fences and crush barriers. One barrier in pen 3 gave way, causing people to fall on top of each other.

Those who survived told of seeing people lose consciousness in front of their eyes.

Supporters continued to climb perimeter fences to escape, while others were dragged to safety by fans in the upper tiers.

At 15.06 Supt Roger Greenwood ran on to the pitch and told the referee to stop the game.

In the chaotic aftermath, supporters tore up advertising hoardings to use as makeshift stretchers and tried to administer first aid to the injured.

The authorities' response to the disaster was slow and badly co-ordinated.

Police delayed declaring a major incident and staff from South Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service at the ground also failed to recognise and call a major incident. The jury decided this led to delays in the responses to the emergency.

Firefighters with cutting gear had difficulty getting into the ground, and although dozens of ambulances were dispatched, access to the pitch was delayed because police were reporting "crowd trouble".

Only two ambulances reached the Leppings Lane end of the pitch and of the 96 people who died, only 14 were ever admitted to hospital.

For the jury in the inquests, police errors in planning, defects at the stadium and delays in the emergency response all contributed to the disaster. The behaviour of fans was not to blame.

Match commander Ch Supt David Duckenfield had a duty of care to fans in the stadium that day, the jurors decided.

They found he was in breach of that duty of care, that this amounted to gross negligence and that the 96 victims were unlawfully killed.

The jury also concluded:

Police errors caused a dangerous situation at the turnstiles

Failures by commanding officers caused a crush on the terraces

There were mistakes in the police control box over the order to open the Leppings Lane end exit gates

Defects at the stadium contributed the disaster

There was an error in the safety certification of the Hillsborough stadium

Police delayed declaring a major incident

The emergency response including the ambulance service was also delayed