Analysis: A very difficult decision on Abu Qatada

- Published

- comments

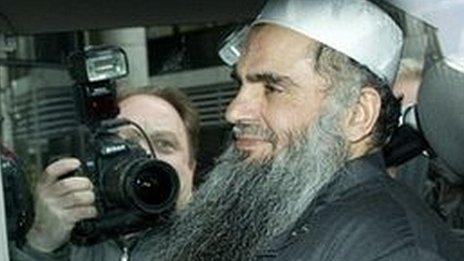

Abu Qatada has never been charged with a criminal offence in the UK

On Monday the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (Siac), the court which deals with national security deportations, will deliver one of its most important judgements in recent years: can Abu Qatada be deported to Jordan?

It is a case where the need for national security rubs up against the UK's legal duties to protect the human rights of suspects.

So what brought us to this point - and what are the issues?

Eight years ago, a Siac judge ruled Omar Othman, external, to use his real name, was a "truly dangerous individual... at the centre in the United Kingdom of terrorist activities associated with Al Qa'ida".

Abu Qatada has never been charged with a criminal offence in the UK. That may strike people as odd - but the case against him is largely based on secret material gathered by MI5 which cannot be used in criminal trials. The government, instead, sought to deport the preacher.

Someone who is deemed dangerous to the UK does not need to be convicted of a crime to be deported. The Home Secretary Theresa May eventually convinced the courts that the preacher's presence, external was not conducive to the public good and judges said he could, in principle, be removed.

'Frantic talks'

But the question remained whether he could be deported to Jordan given its much criticised record on human rights.

The preacher had already been convicted in absentia in relation to two terror plots - and he would be retried for the same offences if returned.

His lawyers said he could be tortured. Secondly, the retrial would be unfair because the key evidence came from men who only pointed the finger at the cleric while Jordan's secret police were torturing them.

The government solved the first problem by convincing judges, including the European Court of Human Rights, that a Memorandum of Understanding from Jordan guaranteed Abu Qatada would be treated properly.

But in January this year, the government lost on the second critical complaint that he would not get a fair trial because Strasbourg decided (largely echoing the UK's own Court of Appeal) that the original torture evidence would be used, external against the cleric.

Strasbourg said it was unconvinced Jordan's legal guarantees against torture evidence would have "any real practical value".

And so, in the absence of any assurance from Jordan on this point, the deportation was off. Cue a media firestorm and weeks of frantic talks between the UK and Jordan over how to solve the situation.

Once Mrs May thought she had a deal with Jordan guaranteeing a fair trial for the preacher, she had to present it to Siac to see if deportation could now be approved, in line with Strasbourg's conditions.

And that is basically what this case is now about. It's not Abu Qatada on trial - but Jordan's legal system.

So has the UK got what it needs?

During two weeks of hearings last month, Mrs May's lawyers told Siac there was now ample documentary evidence proving Qatada would get a fair trial.

The home secretary's lawyers emphasised the Jordanians have enshrined into their constitution an "express prohibition on the admissibility of evidence obtained as a result of torture". They stressed the judges at the State Security Court would be civilian, not military.

The men said to have been tortured into implicating Abu Qatada would be expected to give fresh evidence at retrial - in which they could explain how they were tortured - putting their original tainted statements in context.

'Specific assurance'

But Abu Qatada's lawyers say nothing has changed. In tense questioning of the lead British diplomat, Anthony Layden, it emerged Jordanian ministers would not give a specific assurance on what exactly would happen to the original torture-tainted statements.

Jordan's ministers kept saying that would be a matter for the trial judges. These judges would be able to call the witnesses afresh and dismiss the original statements.

Edward Fitzgerald QC, counsel for the cleric, repeatedly said the UK had achieved nothing new to satisfy Strasbourg's expectations. There was not a single piece of paper declaring the original evidence would be banned from trial, he argued.

So on the one hand there is the government saying it has gone to exhaustive lengths to prove Abu Qatada will be treated justly. It says Jordan is a country that will stick to its word because it has a reform-minded pro-West King and it doesn't want to be part of the international club of states that abuse human rights.

But on the other hand, there is the long-standing opposition of judges to any whiff of torture and questions over whether the UK has got anywhere near to the assurances European judges want.

That judicial opposition to torture evidence didn't just spring from the European Convention of Human Rights.

The Strasbourg judges pointed out in their January judgement that the British courts historically opposed torture evidence long before the convention was written.

They quoted the late Lord Bingham, who said in a 2005 judgement, external that such evidence was "unreliable, unfair, offensive to ordinary standards of humanity and decency and incompatible with the principles which should animate a tribunal seeking to administer justice".

It was a very deliberate reference. They were arguing it is the British rule of law, not just Europe's, that expects Abu Qatada to remain in the UK - and he shouldn't be deported until we are sure that Jordan has cleaned up its act, no matter how politically painful that may be.

Make no mistake. Monday's decision on whether the radical cleric can be deported to Jordan is an extremely difficult one for any judge.

- Published26 June 2014

- Published28 May 2012

- Published11 October 2012