MPs urge readiness over housing benefit cut risks

- Published

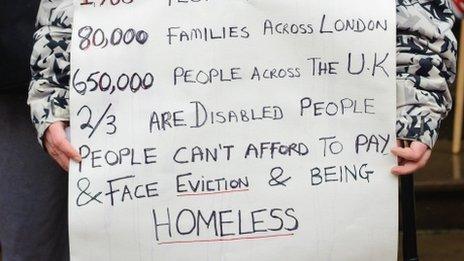

Protests against the housing benefit cut were staged in several cities earlier this month

The government will need to react quickly if a benefit cut for social housing tenants leads to rises in rent arrears and homelessness, MPs say.

Public Accounts Committee (PAC) chair Margaret Hodge said it could have a "severe impact" on low-income families.

Estimates supplied to the BBC by some of the largest housing associations suggest many tenants are not currently planning to move home to avoid the cut.

The government said better use had to be made of social housing stock.

From 1 April, changes to housing benefit (HB) affecting working-age social housing tenants deemed to have spare bedrooms will mean a 14% cut for those with one extra room and of 25% for those with two or more.

The controversial measure - which will see affected tenants lose an average of £14 a week - has been dubbed the "bedroom tax" by Labour, though the government has been at pains to argue it is not a tax but a curb on "spare room subsidies".

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) expects 660,000 social housing tenants to be affected by the cut across Britain.

Ms Hodge said: "The DWP says it can't accurately predict the effects of its housing benefit changes either on individuals or on the housing supply.

"Instead it will rely on a 'wait and see' approach and monitor changes in homelessness, rent levels and arrears so that, where there is a need, it can intervene and respond."

The committee said this placed "greater responsibility on the Department to react quickly when the changes are made".

Ms Hodge warned: "Even small reductions in housing benefit can have a severe impact on the finances of the poorest people."

"The department must decide in advance exactly what actions it will take in response to increases in homelessness or rents."

Stay or go?

The government says the change brings housing benefit for social housing tenants in line with its provision in the private sector, where size criteria already apply.

Intended to reduce a £21bn annual housing benefit bill, the measure is also supposed to encourage greater mobility in the social rented sector.

Of 50 housing associations across the UK contacted by the BBC, as well as a number of local authorities and ALMOs (arm's length management organisations) providing housing on behalf of councils, 21 social housing providers supplied estimates on the number of tenants saying they were planning to stay in their home or downsize.

Among them was Riverside Homes, with 51,493 properties and an estimated 6,602 households affected by the cut.

It estimated that 5,018 - 76% of affected tenants - were currently planning to stay in their home.

Another respondent, Glasgow Housing Association - with 41,400 homes - estimated that of 6,100 affected tenants, some 4,800 - 79% - were currently planning to stay in their home.

Community Housing Cymru Group (CHC), representing 70 housing associations in Wales, estimated that of 40,000 affected claimants, more than 36,000 - 91% - would stay in their homes.

Wales is expected to see a higher proportion of working-age HB claimants hit by the cut - 46% - than any other region of the UK.

'National shortage'

A number of housing associations said that moving large numbers of people considered to be under-occupying social homes was unachievable simply because there were not enough smaller homes available.

Single mother Kellie Parsons explains why she is optimistic about the planned changes to housing benefits

CHC said that 88% of housing associations in Wales would have a mismatch of properties if they tried to downsize all under-occupying tenants facing a benefit cut.

"Not because tenants are needlessly under-occupying larger homes, but because there is a national shortage of affordable homes, especially one and two-bed properties," said CHC spokeswoman Bethan Samuel.

Angela Forshaw, director of housing at Liverpool Mutual Homes (LMH), said half of its stock of more than 15,000 properties comprised three-bedroom homes.

"We have just 2,800 with two bedrooms, so downsizing everyone affected - and most don't want to move - is impossible," she said.

With the vast majority of affected tenants expected to try to find the extra rental money themselves, housing associations raised concerns including:

Increased financial difficulty for tenants

Tenants running up rent arrears

Increased costs to housing associations of rent collection and evictions

A rise in doorstep lending

Damage to communities from increased turnover in social housing and less affordable, larger homes remaining empty

They also warned that people who responded to the benefit cut by leaving social housing could end up claiming more housing benefit in the costlier private sector.

However, for single mother Kellie Parsons the changes provide some hope for larger accommodation.

She lives in a one-bedroom flat with her three-year-old son, Dylan, in Dukinfield, Greater Manchester.

She shares the bedroom with her son, and has been trying to move to a bigger flat for three years - since becoming pregnant.

"The living room is just cluttered with stuff, it's too small, and there's no garden, there's only a veranda which is too dangerous for him so we barely use it.

Caroline Egglestone: "At the moment it's very scary... we are going to be left very short of money"

"There's just no area for him to play, not even outside because there are just too many cars."

She said she hopes that the changes will be an incentive for people to downsize from bigger properties, allowing her to exchange via home swap schemes.

"I've been trying to upgrade for three years. I've been doing it pretty much every single day.

"I think these change of benefits would actually help because people [will] downgrade, so it would help me to move quicker. I'm hopeful, positive about it."

The DWP points out that with one third of working-age social housing tenants receiving housing benefit for homes larger than they need, that amounts to one million extra bedrooms currently being subsidised.

It hopes its measure will enable better use of available social housing stock, and improve work incentives for affected tenants.

"We expect people to respond in different ways to the changes to the Spare Room Subsidy - some will move and some will make up the difference in their rent by moving into work, or increasing their hours," a DWP spokesperson said.

"But when in England alone there are nearly two million households on the social housing waiting list and over a quarter of a million tenants are living in overcrowded homes, this measure is needed to make better use of our housing stock."

- Published16 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013

- Published30 July 2013

'My food budget will halve'

'My food budget will halve'

'Housing benefit change will help'

'Housing benefit change will help'

'A lot of disabled people are scared'

'A lot of disabled people are scared'

'We're going to lose £200 a month'

'We're going to lose £200 a month'