Thatcher papers reveal Tory party split over Falklands

- Published

BBC 5 live's Charissa Chadderton spoke to Chris Collins of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation:

Senior Tories were initially sceptical about going to war over the Falklands, newly released papers from Margaret Thatcher's personal archive show.

A note from the whips' office following Argentina's 1982 invasion reported solid support for military action from some Tory MPs, but others were privately hostile.

The papers have been released in Cambridge by margaretthatcher.org, external.

They show for the first time how deeply split the party was over the Falklands.

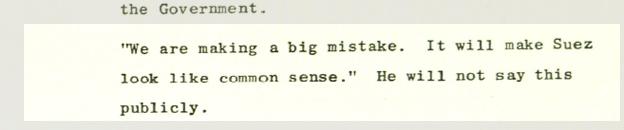

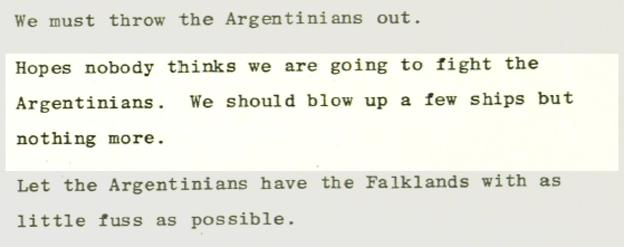

One Tory MP is quoted by the Whips as having said "we're making a big mistake, it'll make Suez look like common sense".

Another suggested letting Argentina have the Falklands with as little fuss as possible.

Others reportedly expressed hopes that "nobody thinks we are going to fight the Argentinians. We should blow up a few ships but nothing more".

The archive is her personal collection of what she thought worth keeping, and includes artefacts as well as documents and papers.

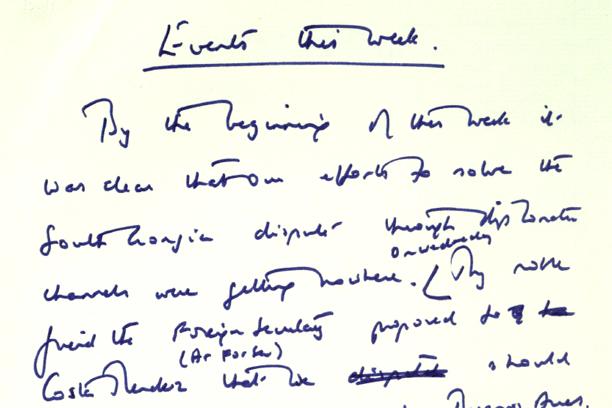

Among other new releases from the Falklands crisis are Mrs Thatcher's handwritten draft notes, external (including numerous crossings out) for her historic speech to the House of Commons on 3 April 1982, where she had to explain to MPs how the invasion had been allowed to happen.

Under fire

There is also a copy of the Daily Mail, dating from just after the crisis broke, with a headline wondering whether "she had the stomach for it".

Speculating as to why she might have kept that particular newspaper, Lord Cecil Parkinson (who was a member of her war cabinet) told the BBC he was sure she was always aware she was being tested.

As Britain's first woman prime minister, he said, she would have known that people would be looking to see how she rose to the challenge of taking the country to war.

Other personal papers released today offer intriguing new insights into her state of mind at the time.

Notes on life at Number 10 showed that much of her day - and nights - were taken up with the war. A diary entry from one of her closest advisors, Sir Alan Walters, revealed she was up at 3:30 am, apparently waiting for front-line reports.

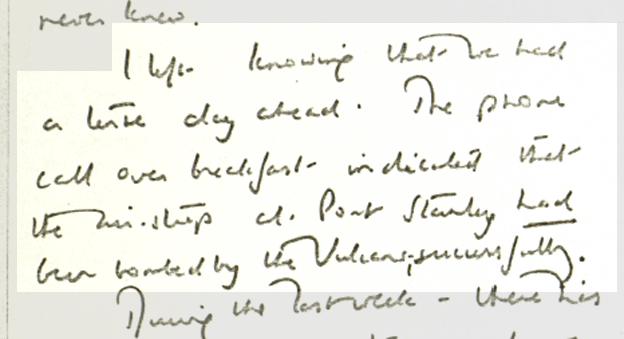

A copy of one thank you note she sent to a constituent, external at the end of April confessed: "I left knowing that we had a tense day ahead. The phone call over breakfast indicated that the airstrip at Port Stanley had been bombed by Vulcans, successfully. During the last week there has been an activity and tenseness I never thought to experience."

But she ended the letter with typical fortitude, adding: "This has happened throughout history and it falls to us to make our contribution to history under the law."

Private grief

As the fight to take back the islands began in earnest, grim reports began to come through of ships being hit and the inevitable casualties. The archive includes the handwritten notes from duty clerks there were passed to her with the bad news.

She sometimes, apparently, could not control her grief. Her former aide Harvey Thomas remembers her breaking down in tears backstage at a constituency event on receiving the news one British ship had been hit. It took her 40 minutes to pull herself together.

"She had received the news either immediately before she came or when she arrived," he told the BBC.

"She was deeply upset that she had to send British sailors to be killed and she was just quietly crying. Then somebody came in to the room and said: 'We have to get out there.'

"When she got back out on the platform she had pulled herself together, she was the prime minister, and she had a country to lead."

Iron Lady

But there is also plenty of the famous Thatcher steely determination reflected in the documents. One draft letter to the US President, Ronald Reagan, shows the no-holds-barred approach she used to rebuff the United States's attempts to broker a peace deal.

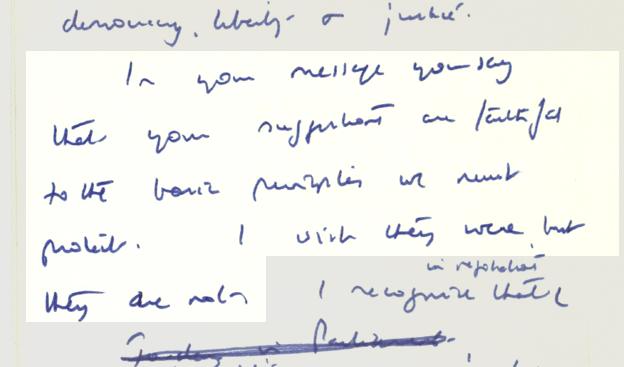

Her handwritten initial draft reveals a refusal to compromise, and even a hint of outrage: "Throughout my administration I have tried to stay loyal to the United States as our great ally." she wrote.

"In your message you say that your suggestions are faithful to the basic principles we must protect. I wish they were, but alas they are not."

That draft was never sent. Her ministers persuaded her to tone it down. The strident passages were replaced with more diplomatic language.

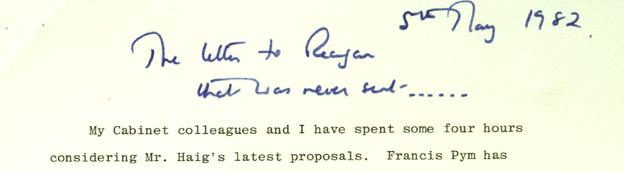

But the fact Mrs Thatcher kept it, and scrawled on the typewritten version of her first draft "the letter to Reagan that was never sent" suggests she felt it reflected her real strength of feeling over the conflict.

- Published22 March 2013