Why the Lawrence family spying allegations matter

- Published

- comments

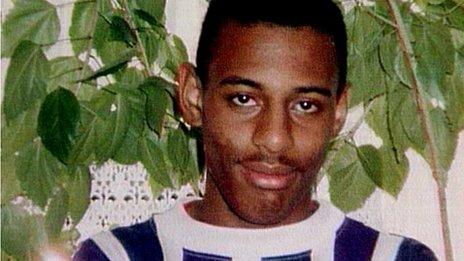

Peter Francis, who says he says he posed as an anti-racism campaigner, served in the Met's now-disbanded Special Demonstration Squad

Peter Francis's revelations that he was allegedly ordered to spy on the family of Stephen Lawrence are staggering.

The allegation on the Guardian's website, external that officers at the Metropolitan Police wanted to smear Doreen and Neville Lawrence raises fresh questions about the appallingly botched original investigation.

But it also echoes uncomfortable allegations about the culture of major police forces, the control of undercover operations - and the oversight of both during that era.

The Met's original failings in the Lawrence case are set out in shocking detail in the Macpherson Inquiry, external.

The inquiry damned the Met as incapable of fulfilling its most basic duties because it was corrupted by institutional racism. Officer after officer, backed up by unquestioned assumptions, failed the Lawrence family because they happened to be black.

Time was wasted investigating the victim. Some officers stereotyped Stephen's friend Duwayne Brooks as just another black teenager with a chip on his shoulder. The list goes on.

How high?

Cynical critics have long whispered that the Lawrence family imagined a great deal of the Met's failings. But it looks like they weren't paranoid after all: someone really was out to get them.

The question is who?

Peter Francis says he was part of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). This was a Scotland Yard unit, not an amateurish operation run from a local police station.

So who authorised his mission to gather "dirt" on the Lawrences and their supporters - and who else knew about it? Lord Condon, London's police chief at the time of the Stephen Lawrence investigation, has denied knowledge of any smear campaign

Who exactly was placed under surveillance? What kind of surveillance and why? Did the police try to recruit people to help dig dirt? Did the operation amount to Peter Francis alone or were there others?

If the operation was officially sanctioned, how high up did Francis's reports go?

Lawrence family barrister Matthew Ryder: "The family are shocked"

Matthew Ryder QC, who has represented the Lawrence family, has said the claims are so serious that they cannot be dealt with through an internal police review - there has to be public disclosure.

But it's far from clear how open the current inquiry into the SDS will be.

Scotland Yard set up the SDS after the political fall out of anti-Vietnam War clashes outside the US Embassy in London in 1968.

The SDS was told to gather intelligence about public order problems and, in the words of HM's Inspectorate of Constabulary, "to build knowledge of extremist organisations and individuals".

Its first targets were campaigners linked to anti-war and anti-nuclear movements. It looked at groups linked to the paramilitaries in Northern Ireland. It later began infiltrating animal rights campaigns and the environmental protest movement. Officers went in deep - for years at a time.

The politically sensitive nature of its work is clear from the fact that government directly funded its activities - and ministers received an annual update on its activity until 1989. The unit was eventually closed down in 2008.

There are a number of serious allegations which have been made against the SDS.

One senior undercover officer, Bob Lambert, is alleged to have co-authored the controversial "McLibel" leaflet

The first is that officers adopted the names of dead babies, a spycraft technique best described in Frederick Forsyth's blockbuster, The Day of the Jackal.

The second is that some of these officers then had sexual relationships with women who, to all intents and purposes, were used to provide additional cover. One relationship led to a child.

The most recent allegation is that one of the senior undercover officers, Bob Lambert, co-authored the controversial "McLibel" leaflet. An MP separately used parliamentary privilege to allege that the former officer-turned-academic was involved in a shop firebombing as part of his animal rights cover, something he has denied.

Operation Herne, the internal police investigation into the SDS, began in October 2011, but no-one has so far been arrested and accused of wrongdoing.

Derbyshire Police's chief constable Mick Creedon has taken over the investigation from the Met - and he is facing pressure from MPs to get to the bottom of what was going on. His report on the baby names affair is expected soon.

Home Office minister Damian Green has recently told the Commons Home Affairs Committee, external that there is a line that must not be crossed by undercover officers - and that police officers should face criminal charges if they broke the law.

More broadly, ministers believe that the modern legislation that now covers covert police work (known as "Ripa", external) makes that line much clearer than it was 20 years ago.

'Force within a force'

As for the Met itself, its initial statement on the latest allegations was curious. It confessed concern and concluded: "At some point it will fall upon this generation of police leaders to account for the activities of our predecessors, but for the moment we must focus on getting to the truth."

This line has echoes of unrelated alleged wrongdoing levelled against other British police forces.

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, albeit in a completely different security context, the then Royal Ulster Constabulary was accused of harbouring "a force within a force" that wasn't accountable to anybody. Some of its own officers accused their colleagues in Special Branch of having lost their way and forgetting who they were there to serve.

In an entirely different situation, there are echoes of the treatment of the Lawrences in the allegation that some South Yorkshire officers smeared the victims of the Hillsborough disaster to cover up their catastrophic mistakes.

The common factors between these three unrelated controversies is that they all happened in an era when independent inspection of the police was less than ideal - and oversight of covert work somewhat random.

They all raise serious questions about whether the officers involved were corrupt, working against the public good.

Jack Straw, the home secretary who ordered the Macpherson report, has demanded to know what was withheld from that public inquiry because the police would have been under a duty to disclose everything relevant.

So who took that decision? Why - and who else knew?

- Published3 January 2012

- Published24 June 2013