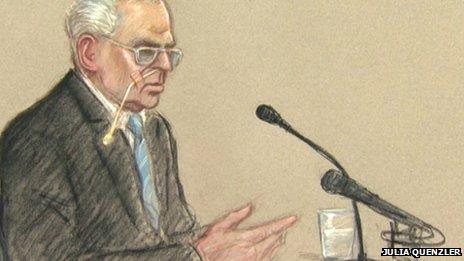

Ian Brady: Witnessing the tribunal evidence

- Published

Ian Brady is fighting to return to prison, though he accepts he will never be freed

Moors Murderer Ian Brady spoke publicly for the first time in 47 years as he appeared before a mental health tribunal at Ashworth Hospital.

In a plain suit and tie, and sitting on one side of a u-shaped table alongside his lawyers, the scene resembled a dull mid-year office sales presentation.

But what marked this out as something very different were the dark glasses Brady never removed, the feeding tube dangling from his nose - and the day-long sparring with the panel which will almost certainly decide how he will live his final years.

The last time Brady, now 75, had been heard in public was in 1966 at Chester Assizes, during his murder trial.

He was eventually found guilty of three child murders and jailed for life. He and his accomplice Myra Hindley later confessed to another two.

Brady was moved from prison to Ashworth high-security psychiatric hospital in Merseyside in 1985 - but is fighting to be declared sane so he can be moved back to prison.

'Side-stepping questions'

As he began speaking to the tribunal with a soft Glaswegian accent, every word he uttered was weighted.

He would sometimes qualify what he was saying with complex sub-clauses and digressions into the recent history of this, that and the other.

Sometimes he would be more direct - accusing Ashworth Hospital of turning patients into "zombies" by filling them with "false" drugs.

Either way, he always had a point - even if the point took five minutes to reach - and he always had an answer.

Was he suffering psychotic hallucinations when he talked to himself? Who doesn't talk to themselves, he replied. Wasn't he clinically paranoid? It was "sensible suspicion" that you learn while doing your time. Why did he hide in his room? He was avoiding "negative, regressive, provocative" staff.

But more often than not, Brady side-stepped the questions by answering with his preferred alternative.

Occasionally he would give an immediate direct answer, such as when he rejected the medical assessment that he is psychotic - the key criterion for keeping him as Ashworth.

'Self-possessed'

But other exchanges were bizarre. He told the tribunal he had been faking psychotic symptoms while in prison by using the Stanislavski method acting technique. With a degree of arrogance, he chided the panel when it asked him to explain.

Brady is aware of what the world thinks of him.

He described his own crimes as historically comparable to those of Jack the Ripper because of the way his murders had entered the public conscience - crimes against a backdrop of "Wuthering Heights and the Hounds of the Baskervilles" as he put it.

But his body language changed as the day went on. Despite warming to his theme and trying to command the room, he did not like being put on the back foot during cross-examination.

He sat back, hunched his shoulders, crossed his arms and, occasionally, jabbed his finger at the Ashworth team he is said to hate.

At Ashworth, he argued, the world is different. Both unorthodox and banal actions are considered a symptom of psychosis. Dropping his glasses case and muttering to himself as he picks them up is read as a sign of mental illness, he claimed.

In contrast, he appeared to think that his time in prison had been rosy, doing "honest time".

Prison barber

He had worked as a prison barber and also produced Braille books. He hobnobbed with infamous inmates like the Krays, he said.

So does he really want to go back to prison - and why?

At the start of this tribunal, the BBC was reporting that Brady was being force-fed on a hunger strike and wanted to die. The truth is more complicated.

Brady went on hunger strike as a protest against Ashworth. But he also co-operates with taking food down a tube. His nurse says he eats toast and instant soup.

Brady, now 75, and Myra Hindley tortured and murdered five children

Ashworth's view is that the tube-feeding is about his attempt to exert some control over the authorities - it is not a real hunger strike at all.

On Tuesday, he repeatedly ducked questions about the hunger strike.

So Eleanor Grey QC, for the hospital, tried another tack. She asked him straight questions about whether he was eating.

After much tedious sparring, Ms Grey stood her ground and Brady had to give in. "No I'm not eating," came the answer. It appeared to be in complete contradiction to his physical appearance and the evidence.

But Brady tried to wrestle control back.

He insisted that whether or not he was eating did not matter. What mattered was whether he was sane.

"That is what I am here to prove so I can get on with going to prison. My plans [if I get there] are nothing to do with anyone else," he said.

"I knew from day one that I'm in until I'm dead. [Freedom or parole] does not enter my sphere of thought."

So beyond the legal test of mental capacity, the real question in this tribunal is one of control.

Brady harbours grievances about Ashworth. It is impossible on the outside to know which are real, which are imagined and, critically, which he may be using in a manipulative game driven by his psychopathic tendencies.

In his mind - or at least the one he presented to the tribunal - his detention at Ashworth is "political" because Britain is a "prehistoric" society that allows ministers to decide what happens to people like him.

But given that he does not want doctors deciding either, it is not quite clear who he thinks should be in control - other than Ian Brady.

- Published13 June 2013

- Published25 June 2013