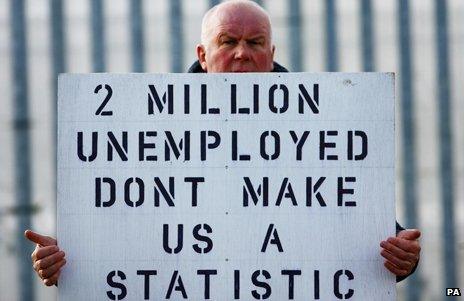

Viewpoints: How should long-term unemployment be tackled?

- Published

- comments

The long-term unemployed may have to undertake work placements in return for their benefits, under changes being unveiled by Chancellor George Osborne.

From April 2014, people who are jobless after being on the work programme for two years will face three options - a community work placement; taking part in training; or visiting a job centre every day - or face losing benefits.

Although the UK unemployment rate has fallen in recent months, the number of long-term unemployed has not fallen.

How should long-term unemployment be tackled?

Chris Goulden, head of poverty at social policy charity the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Most would agree that people with the misfortune to be long-term unemployed need intensive, personalised help to get back into a job.

International evidence shows that a full package of support and the right kind of work experience - ideally with pay and the prospect of a proper job at the end of it - is crucial.

Forcing people into jobs at threat of financial sanction risks pushing them out of the system entirely and doesn't help them get a real job, which is not cost-effective.

Neither can we ignore the extent of poor-quality jobs in the UK labour market. Getting on the ladder is vital but we need better and wider routes upwards out of poverty.

Graeme Cooke, research director at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR)

There is nothing wrong with expecting the long-term unemployed to undertake work experience or an intensive job search, in fact it can really help.

When done right, they give people the work habits and employability skills that employers are looking for.

What's crucial is that schemes are designed to make people more likely to get a job, not less.

Today's announcement builds on an earlier "mandatory work activity" pilot, which was found to have had no impact on future job prospects, only short-term breaks in JSA claims, and increased the numbers on disability benefit.

Instead, drawing on the successful Future Jobs Fund, external, the government should guarantee a real job, created by the charitable sector and paid at the minimum wage, to anyone who has been out of work for a year.

And insist that they take the job or lose their benefits - limiting the time someone can be unemployed.

Becci Newton, senior research fellow at the Institute for Employment Studies (IES)

The social and economic consequences of long-term unemployment are well known.

For individuals, it can mean detachment from the norms of work, skills losing currency and loss of confidence due to multiple knock-backs.

Mechanisms that re-build labour market attachment are valuable but there is a need to recognise the multiple barriers faced, including the uneven geographic dispersion of work, which poses the challenge of economic regeneration.

Long-term unemployment among young people is particularly problematic, and it is crucial that they receive interventions that help them to achieve traction in the labour market, which may include skills development as well as workplace experience.

Kevin Green, CEO of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation

The longer someone is out of work the more challenging it becomes to find a job.

Their skills and experience become out of date and their confidence is dented.

Specialist help should kick in quickly, but currently the Work Programme is targeted at people who have been unemployed for a full 12 months.

The benefits trap is also a real problem.

People can be reluctant to take a temporary or part-time job even though it would be a great first step back into the workforce because they are worried that when it ends they might lose their benefits.

Welfare reforms must tackle this perceived barrier.

The government should tap into the expertise of professional recruiters.

It's their job to have good relationships with employers and to understand their local labour markets.

This can make them better placed than Jobcentre staff to provide advice about local opportunities.

They can also give free, personal advice to jobseekers about how to perform well in interviews and how to make the most of themselves on their CVs.

Prof Paul Gregg, director of the Centre for Analysis and Social Policy at the University of Bath

Very long-term unemployment (2+ years) is strongly cyclical, almost disappearing from 1998 to 2009, but has returned with the protracted period of poor economic performance.

It is thus not a new phenomenon and a large range of policies have been tried before. We have a very good idea of what does and does not work.

The effect of requiring people to go into work placements depends a lot on the quality of the work experience offered.

They have three elements: first, some people leave benefits ahead of the required employment.

This is called the deterrent effect and is stronger the more unpleasant and low paid (eg work for the dole) the placement is.

Then, whilst on the placement, job search and job entry tend to fall off as the person's time is absorbed by working.

Finally, the gaining of work experience raises job search success.

This is stronger for high-quality job placement in terms of the experience gained and being with a regular employer who can give a good reference if the person has worked well.

The net effect of many such programmes, including work for the dole, has often been little or even negative.

But the best effects come where job search is actively required and supported when on a work placement, where the placement is with a regular employer rather than a "make work" scheme and where the placement provider is incentivised to care about the employment outcomes of the unemployed person after the work placement ends.

John Salt, website director of Totaljobs.com

Long-term unemployment is a major problem for many jobseekers, as those who have been out of work for a long time can lose confidence and feel that they have become unattractive to employers.

George Osborne does sound as though he is unfairly trying to shift the onus onto the unemployed, when the government aren't really doing enough to generate new jobs.

Despite this, the work placements outlined should help the long-term unemployed in theory, by giving them the chance to develop work-related skills and so on.

The most important thing for those out of work is the development of new skills and experience, whether this is through work placements, free courses or taking on new responsibilities, along with maintaining their confidence and believing in their ability to get a job.

- Published30 September 2013

- Published30 September 2013

- Published11 September 2013