Press regulation: Privy Council grants royal charter

- Published

- comments

Publishers fear the royal charter will allow governments to encroach on press freedom

A new cross-party royal charter on press regulation, external has been granted by the Privy Council, the government says, after the newspaper industry lost a last-minute court challenge.

Court of Appeal judges refused newspaper publishers an urgent injunction to stop ministers seeking the Queen's approval for the charter.

Editors had argued their alternative proposals were not properly considered.

The charter will create a watchdog to oversee a new press regulator.

Media organisations will be free to sign up or stay outside the new system of regulation.

The matter of press regulation emerged following the phone-hacking affair and subsequent Leveson Inquiry into the ethics and practices of newspapers.

Publishers had until 17:30 GMT on Wednesday to try to stop the politicians' charter being approved, which they argue could allow governments to encroach on press freedom.

Earlier on Wednesday, High Court judges refused publishers an injunction ahead of the Privy Council meeting and said there were no grounds for a judicial review.

'Deeply illiberal proposal'

Hours later publishers made a second attempt to gain an injunction through the Court of Appeal, pending a planned appeal against the High Court's ruling.

However, Lord Dyson, Master of the Rolls, sitting with Lord Justice Moore-Bick and Lord Justice Elias, refused to grant an interim order.

In a joint statement, the newspapers said the newspaper and magazine industry had been denied the right properly to make their case that the Privy Council's decision to reject their charter was "unfair and unlawful".

The newspapers learned their alternative proposals had been rejected by the Privy Council earlier this month because they did not comply with certain principles from the Leveson report, such as independence and access to arbitration.

A spokesman for the Department for Culture Media and Sport said: "Acting on the advice of the government, the Privy Council has granted the cross-party royal charter.

"Both the industry and the government agree independent self-regulation of the press is the way forward and that a royal charter is the best framework.

"The question that remains is how it will work in practice; we will continue to work with the industry, as we always have.

Harriet Harman: "It really is time for a new press complaints system"

"A royal charter will protect freedom of the press whilst offering real redress when mistakes are made.

"Importantly, it is the best way of resisting full statutory regulation that others have tried to impose."

The executive editor of the Times, Roger Alton, said: "It's extraordinarily depressing and very, very alarming that in one short spell a hundred-year-old tradition of the press of this country, that's independent, free of political interference, has been cast aside."

Fraser Nelson, editor of the Spectator newspaper, said: "Now it's down to the newspapers to decide if they are going to sign up to this deeply illiberal proposal or whether they should stand up for press freedom."

He said his industry was creating its own regulator - the toughest regulator in the western world - which did almost everything Lord Leveson asked for but not at the behest of politicians.

He said he would be surprised if any newspapers sign up to the new system of regulation.

Editor of the Daily Telegraph Tony Gallagher tweeted:, external "Chances of us signing up for state interference: zero."

The Privy Council, whose active members must be government ministers, meets in private to formally advise the Queen to approve "Orders" which have already been agreed by ministers.

This latest Privy Council meeting, held at Buckingham Palace, was attended by Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt, Culture Secretary Maria Miller and the Liberal Democrat Justice minister, Lord McNally of Blackpool.

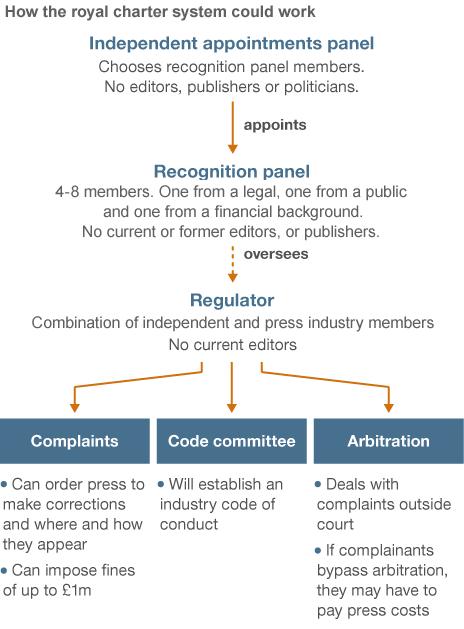

Both politicians and the press agreed there should be a "recognition panel" to oversee a press self-regulation committee with powers to impose fines of up to £1m on newspapers for wrongdoing.

Some parts of the system have been omitted for clarity

However, the press charter required industry-wide approval for any amendments, while the politicians' version - backed by the three mainstream parties - can be changed by a two-thirds majority in Parliament.

Hacked Off, the lobby group which has led the campaign for tighter regulation, said: "News publishers now have a great opportunity to join a scheme that will not only give the public better protection from press abuses but will also uphold freedom of expression, protect investigative journalism and benefit papers financially.

Hacked Off's Brian Cathcart: "The royal charter is good for press freedom and will give protection to the public"

"The press should seize the chance to show the public they do not fear being held to decent ethical standards, and that they are proud to be accountable to the people they write for and about."

Bob Satchwell, executive director of the Society of Editors, said of the royal charter's approval: "This is disappointing and it is a pity the Queen has been brought into controversy.

"Royal charters are usually granted to those who ask for one - not forced upon an industry or group that doesn't want it.

"Those who seem to want to neuter the press forget that there are 20 national papers, 1,100 regional and local papers and hundreds of magazines who have not done any wrong but they are willing to submit themselves to the scrutiny of the most powerful regulator in the Western world, so long as it is independent of politicians now and in the future."

Standards code

Under the royal charter, the Press Complaints Commission will be replaced by a new regulator with greater powers, and a watchdog - the recognition panel - which will check the regulator remains independent.

The regulator, set up by the press but without any editors on the board, will draw up a standards code and will be able to impose fines of up to £1m.

It will also provide a speedy arbitration service to deal with complaints.

The recognition panel will be made up of between four and eight members, none of whom can be journalists, civil servants or MPs.

Newspapers and magazines can chose whether to sign up to the new system of regulation, but those who do not, risk exemplary damages if they lose a libel case and may also be liable to pay the complainant's costs, whether they win or lose.

By contrast, under the royal charter system, news organisations will first go through an arbitration system with any complainant. Any complainants who want to go to court without arbitration may be expected to pay the media organisation's costs.

- Published30 October 2013

- Published12 October 2013

- Published11 October 2013

- Published30 October 2013