Building on the suburban dream

- Published

- comments

John Betjeman may well be turning in his grave: there are plans afoot for the "urban intensification" of London's suburbs.

The "Supurbia" proposal, supported by the capital's Deputy Mayor and housing chief, envisages tens of thousands of new homes a year in "thriving, vibrant and sustainable" communities where residents share everything from cars and bicycles to mowing machines and rowing machines.

The very phrase "urban intensification" will raise hackles, of course. But the acute shortage of affordable homes in the South East has forced planners and developers to consider how to get more from what are described as "London's very low density and often under-occupied suburban districts".

The people behind Supurbia are quick to point out they have no intention of "garden-grabbing" or concreting over green spaces. In a slightly unfortunate choice of phrase, they promise the objective is "to build on (sic) the inherent quality of the suburbs - individual homes on their own plots with easy access to public and private open space set in a verdant environment."

It is, however, a far cry from the original promise of Metro-land in the brochures of the 1920s. Living in suburbia was then portrayed as the seductive dream of a spacious and modern Tudor-style home and garden set in beautiful countryside.

It was all about independent living away from the 'turmoil and bustle of Town'. "Out and on, through rural Rayner's Lane / To autumn-scented Middlesex again," as Betjeman famously described the journey along the Metropolitan line.

The new vision of London's suburbs imagines a very different life-style choice for the residents of Metro-land.

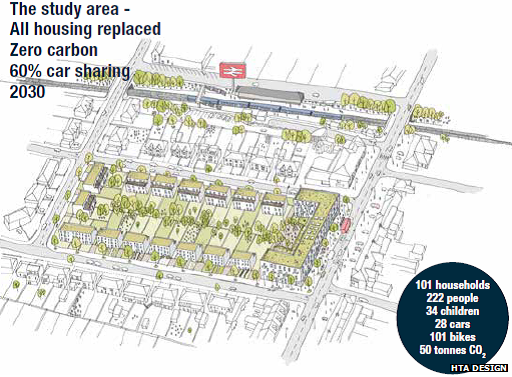

"The project will explore how a programme of urban intensification might trigger changes resulting over time in a much improved fit of population in accommodation; more sustainable, efficient and affordable," the brochure from HTA Design explains.

The company calculates that doubling the density of just 10% of the existing stock of "poor quality semis" in the outer London Boroughs would create the capacity for 20,000 new homes a year.

And using census data, they have also worked out that if 10% of those semis "was fully rather than under occupied it would accommodate 100,000 more people".

They know it is going to be a hard sell. "Whilst it's clear that Nimby attitudes thrive in outer London, we seek to explore the extent to which self-interest may overcome resistance to change," HTA Design says.

So what will the incentive be? I put the question to HTA Design managing partner Ben Derbyshire. "The ageing population who under-occupy homes they have inhabited over many years are sitting on an equity gold mine," he explained.

"They have poor (or no) choice when it comes to down-sizing to release their equity and so to offer 'HAPPI' style, third age accommodation in their neighbourhoods is to liberate a real estate resource with huge potential."

'HAPPI, external' refers to a Homes and Community Agency panel set up to consider new ways to meet the housing needs and aspirations of older people. "In suburbia, we need to provide homeowners with the means to profit from the development potential of their asset," Derbyshire argues.

He answers fears that increasing density will see house values decline by pointing out that "the highest plot ratio of any housing in London is to be found at Albert Hall Mansions in Kensington Gore", one of the capital's priciest neighbourhoods.

Even if they can overcome the Nimbyism for which the suburbs are notorious, there is another major challenge for the Supurbia project. All these extra people will put huge pressure on local services and resources. For a start, where will they park their cars?

The answer to this question, apparently, is communities where people share. "Instead of cars sitting on roads or car parks for large parts of the day, they will be in use, shared," the Supurbia brochure proclaims.

Ben Derbyshire is confident that future suburbanites won't mind giving up their parking spot. "Car ownership and aspiration is rapidly changing with young Londoners showing an increasing disinterest," he claims. "Public transport in London has benefitted from huge investment and the costs of car ownership are a significant disincentive."

What about pressure on energy supplies? "No new grid infrastructure should be needed," it is claimed. To avoid the problem of huge extra demand at peak times, there will be battery storage of energy from the grid when it is cheap, and from solar panels. Residents will be encouraged to use timers to control when washing gets done.

It is not just cars and energy the planners think 21st-Century Metro-landers might share. The project envisages community hire schemes for "equipment that many people own but never actually use, drills, hedge trimmers, car washers, exercise equipment, projection facilities, construction tools, mowing machines."

The Supurbia project is work in progress. London's deputy mayor for housing, Richard Blakeway, tells me there are challenges it will "need to explore and test in a specific area". A pilot project is on the cards.

And for lovers of Betjeman, it is worth stressing that the Metro-land dream was never reality. Many of the capital's suburbs are made up of dreary, cheaply-built semis that offer little or nothing in terms of a solution to the desperate demand for affordable homes within commuting distance of the capital.

"Urban intensification" may raise hackles, but there is an urgent need for creative answers to the housing crisis in London and the South East. Supurbia offers ideas for a possible way out of the mess.