How do you define Islamist extremism?

- Published

- comments

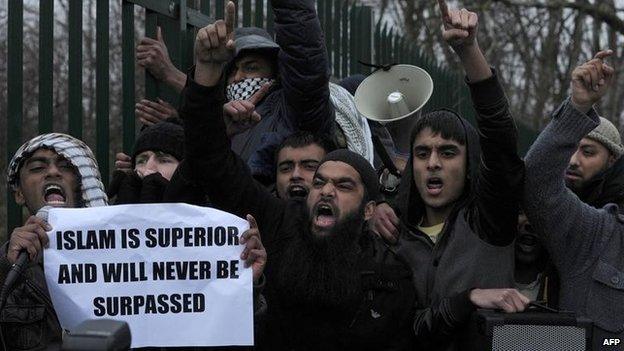

The government has broadened its definition of extremism to include "opposition to British values"

The Birmingham Trojan Horse row has reignited a long and difficult debate over defining Islamist extremism.

Today, the government defines extremism as "vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs".

It goes on to say that Islamist extremism is an ideology that accuses the West of perpetrating a war on Islam.

If that definition is now clear, it wasn't always so.

Back in the early 1990s, London became a hub for an international network of predominantly Arab Islamist thinkers, many of whom had fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

These former fighters were seeking safe havens because their support for Islamic states meant they posed a security threat to the despotic regimes in their own countries.

They persuaded the UK that they would not pose an extremist threat here and were allowed to settle.

This uneasy situation didn't last. Jihadists - such as the preacher Abu Hamza - ultimately supported Osama bin Laden's anti-Western message. The 9/11 attacks served only to convince critics that the UK's security services had made a catastrophic error of judgement and allowed extremism to flourish.

Banned

In the wake of the later 7/7 attacks on London, Tony Blair's government signalled it would not only hunt down suspected terrorists, but also turn its attention to anyone promoting the ideology that could be linked to violence.

There were proposals to close extremist mosques, bookshops and other organisations. The government broadened the range of terrorism offences and banned one group whose members had committed terrorism offences.

Tony Blair and David Cameron both said they would outlaw Hizb ut-Tahrir, but the group remains legal

Many parts of this package were dropped because of disagreements in Whitehall over what constituted extremism.

For instance, Tony Blair said he would ban Hizb ut-Tahrir, a group that supports a single Islamic state. Despite David Cameron making the same pledge while in opposition, the group remains legal, external to this day.

Inside Whitehall, officials tried to work out which community groups were best placed to receive more than £50m earmarked for projects designed to prevent extremism.

But in hindsight, many of the bets were poorly placed. While many groups took the cash and used it to do some local good, a great deal of them didn't seem to have any means to combat extremism - not least because nobody seemed to agree what it was.

In the end, a highly critical report from MPs accused the government, external of alienating some of the many people it was trying to reach.

Integration or separation?

David Cameron came into office with (whether you agree with it or not) a much clearer definition of what constituted extremism. Michael Gove, the education secretary at the centre of the Birmingham Trojan Horse affair, was one of the architects of what became known as the Munich speech, external.

In it the PM said the government needed to be "shrewder" in dealing with groups that were part of the problem, even if they were not violent themselves.

He said that groups wishing to work with government had to pass tests such as whether they believed in human rights, including for women, the rule of law and democracy. Did they encourage integration or separation?

In other words, his definition of extremism comes down to a question of whether society fractures into "us and them".

In that context, it's not hard to see why the Birmingham schools affair has become so important to ministers.

Too extreme

Since the Munich speech, the government has massively cut funding to Muslim community groups that it felt did not meet these tests.

One of the groups that lost out was a south London-based organisation called Street. It previously had the ear of some in Scotland Yard because it had intervened to stop gang violence and al-Qaeda recruitment.

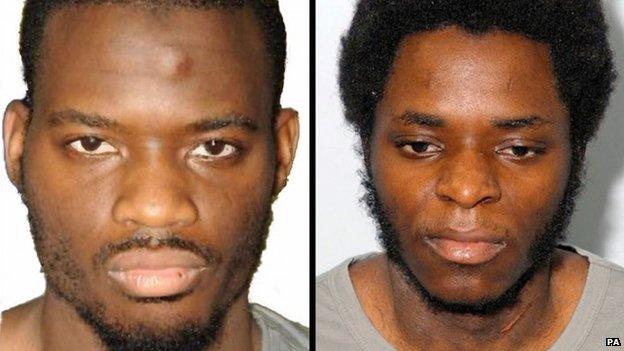

Could the killers of Fusilier Lee Rigby have been stopped before they became violent?

In the new landscape, it was deemed to be too extreme because its members tended to follow a very conservative Saudi-influenced interpretation of the faith.

Street's founder told the BBC last year that the organisation had identified one of the killers of Fusilier Lee Rigby as a possible threat - and he believed he could have been turned away from violence had his group still been operating.

The prime minister's Extremism Task Force, set up after the murder, doesn't analyse whether the killers could have been stopped. But it cements the government's current broader definition, external of extremism.

The definition it uses, outlined at the top of this blog, is much clearer than it once was - and the detailed guidance makes clear that schools should support "British values".

Seven years ago, the future Education Secretary Michael Gove wrote that "there is something rather un-British about seeking to define Britishness, external".

He argued that Britishness was something best demonstrated through action rather than described in abstract terms.

And that's why the state of a small number of predominantly Muslim schools in Birmingham, and how the government and other bodies propose to change them, may turn out to be one of the defining moments in modern multicultural Britain.

Update 12 May: Since I wrote this blog, my colleagues Tim Johns and Emma Hallett have written an excellent piece on life in Christian fundamentalist schools - and why some former students say they leave children ill-prepared for life in the real world. It is well worth reading in the context of the current debate.

- Published10 June 2014

- Published9 June 2014

- Published9 June 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published24 April 2014

- Published20 March 2014

- Published19 December 2013