From tabloid heyday to 'witch-hunt' - the hacking trial

- Published

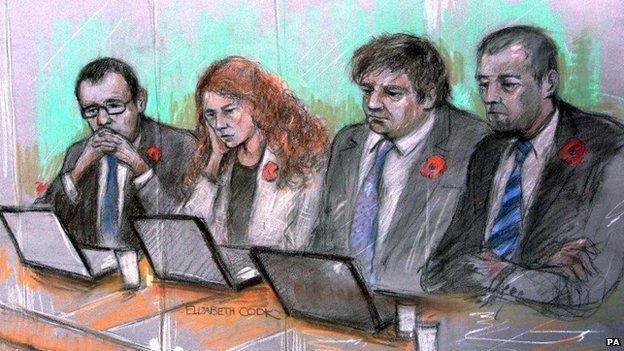

Rebekah and Charlie Brooks sit side-by-side in court, between Andy Coulson and Mark Hanna

After 130 days of evidence, the "phone hacking" trial is almost over. The back-story to this extraordinary tale has its roots in the days when tabloid journalism was in its heyday, and the protagonists at the height of their powers.

But as one of the barristers involved in the trial described it in a private moment, this was "the trial that nobody wanted".

The scale of the prosecution was immense. The jury saw some 3,000 documents - sometimes on paper and sometimes on specially-installed TV monitors.

Hours were lost re-arranging paper in the cramped jury box - and "file management" was a chore that both the jury and the overworked court usher had to endure.

Humour deflected the drudgery. "This morning, we are going to do some exciting things with dividers," Andrew Edis QC, the senior prosecutor, once announced to an incredulous court.

Many of the documents and phone records were seized from private investigator Glenn Mulcaire as part of the original phone hacking investigation - Operation Caryatid - which was set up in late 2005 to find out who was listening in to the voicemails of members of the royal household.

The haul of evidence was so overwhelming that both he and Clive Goodman, the newspaper's then royal editor, pleaded guilty the following year.

But the full extent of hacking was not exposed before now. This trial's analysis of the mother lode of data has finally answered many questions about the practices at the News of the World.

Yet one question hung over this trial throughout the 130 days of evidence: Why did the Metropolitan Police's original investigation fail to get to the bottom of the affair in the first place?

Another affair figured highly in the trial - the one between Rebekah Brooks, now cleared of all charges, and Andy Coulson.

'Concentration and control'

In the first few days of the trial, the defendants sat in the the glass-screened dock, with not a security guard in sight, in the order in which their names appeared on the indictment.

Mrs Brooks sat next to Coulson. Her husband, Charlie Brooks sat four seats along. Polite conversation was exchanged between the two former editors and lovers. Sometimes, after a dramatic moment, they would engage in deep discussions or shake their heads in unison. Later, after a plea from her lawyer, she was allowed to take a seat next to her husband.

The trial turned out differently for Andy Coulson and Rebekah Wade

In another rare concession, the defendants were permitted to take their morning coffees into the dock - not that anyone ever asked permission. The press took their lead from Mrs Brooks et al and relished being able to begin the day in court 12 with a dose of caffeine dressed up in a latte.

Only after complaints about empty containers being left behind was the privilege revoked by an apologetic Mr Justice Saunders.

As the trial developed, Mrs Brooks's and Coulson's defence case became clear. It was simple; they did not know what was going on under their editorships.

Mrs Brooks told us she had paid a public official for a story - about a plot by Saddam Hussein to bring anthrax to the UK - but she resolutely denied knowing anything about phone hacking until the arrests of Goodman and Mulcaire.

She spent 14 days in the witness box and in that time we learnt of some of the friendships and contacts she made through her work.

Paul and Sheryl Gascoigne figured prominently early in her career but then, as she moved up the corporate ladder, she moved on to senior lawyers, politicians (including three prime ministers) and a former commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

"I had a pretty good relationship with the late chief constable of Greater Manchester." she casually revealed.

Her performance, in giving evidence, was a master class in concentration and control - although on the sixth day her lawyer appealed to the judge for a break, saying she was exhausted and not sleeping.

Coulson told the jury that he found out about phone hacking in 2004 two years before the first arrests. He said he told the reporter concerned to stop doing it - but he still used the information to expose an affair between the then home secretary David Blunkett and a married woman. His admission went further: "This was about someone having an affair, and given what was going on in my life, the irony was not lost on me."

'Witch-hunt'

Only once did Coulson appear flustered when Mr Justice Saunders, tired of his refusal to admit he lied to Mr Blunkett about the source of his information, demanded a "yes or no" answer to the question, "Did you tell an untruth?"

Huge publicity surrounded the case and the personalities involved.

Rebekah and Charlie Brooks leave court, cleared of all charges

In his opening remarks Mr Justice Saunders was moved to tell the jury to ignore anything they may see or hear about the case outside court.

"The defendants are on trial, but British justice is also on trial," he said.

Only the day before, in the absence of the jury, Mrs Brooks's legal team had tried to have the case thrown out because of adverse publicity. The front page of the latest edition of the satirical magazine Private Eye showed Mrs Brooks at the Leveson Inquiry with the headline "Halloween Special". "This is a campaign against Mrs Brooks," and a "blatant attempt to scupper the proceedings," was the bitter refrain from Mrs Brooks's lawyer Jonathan Laidlaw QC.

He would return to the motif at the end of the trial. In an extraordinary closing speech Mrs Brooks's lawyer likened the prosecution of his client to a "medieval... witch-hunt" adding, "as you know the defining feature of a medieval trial for witchcraft was that the accused could never win".

But in the end, she did, and walked out of court a free woman.