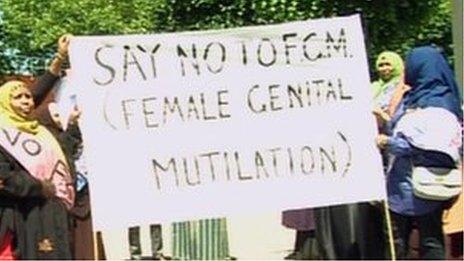

FGM: A child abuse 'out of the ordinary'

- Published

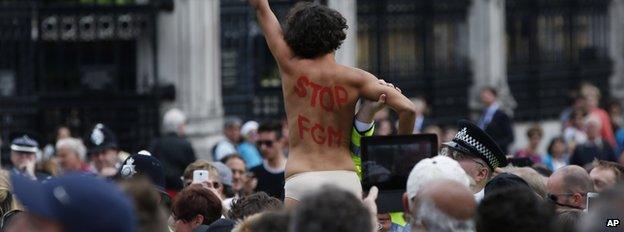

The one-day Girl Summit in London is discussing ways to end female genital mutilation and forced marriage

London is hosting an international summit, external to discuss putting a stop to female genital mutilation. In the UK as many as 170,000 women and girls have been cut but why does the practice persist and what does it mean for the victims?

"They love their children a lot," Jay Kamara-Frederick says of the parents who have their daughters cut.

"They just want their child to be part of an out-dated, ancient tradition."

As a young teenager Jay, now in her thirties, was taken by her family from the UK back to Sierra Leone.

She was told she was going to join a woman's society and that it would "empower me as a woman".

But it was not until she was an adult that she realised what had been done to her 10 years earlier. And where that memory should have been, she says, there was instead a void.

"They say when people are traumatised that happens to them," Jay says. "That part of me was totally gone."

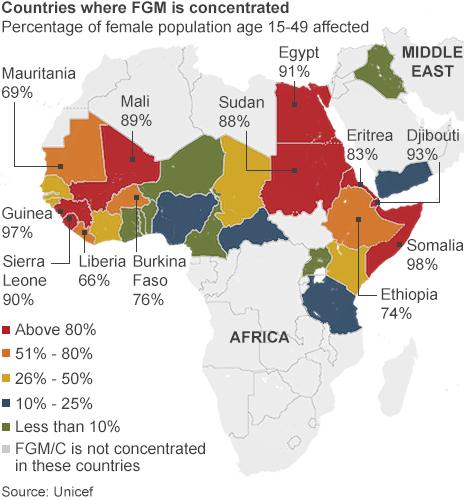

Map shows the 29 countries where Unicef has found that FGM is concentrated. The practice is also found in pockets of Europe, North America and Asia

There are various types of female genital mutilation, or cutting. Among them is the partial or total removal of the clitoris.

Now a marketing consultant and some-time campaigner against the practice, Jay says what happened to her is not a subject easily discussed in her "very traditional" family.

"I really respect my mum's view, to be quiet on the issue," she says, smiling. "But what I love about my mum is that she respects my view to keep talking."

'Loving and caring'

Jay's story is far from unique - the Home Affairs Select Committee has estimated there could be 170,000 victims in the UK alone.

It is is a form of child abuse that is "out of the ordinary", says John Cameron, head of child protection at the NSPCC.

"Speaking out is a real problem," he adds, warning victims within families can "go under the radar".

The centuries-old tradition is reportedly on the decline in northern Somalia

An NSPCC helpline introduced a year ago has already had almost 300 calls, prompting nearly 130 referrals to the police and children's services.

The following cases were among those calls (identifying details have been removed):

A doctor rang after becoming concerned about a patient whose father was preparing for his daughter to visit Somalia, but wouldn't give the doctor any details about why she was going there. The patient and family's details were passed on to children's services to follow up

A member of the public called the helpline to report that a female relative was soon to be circumcised against her will. His relative was being confined to her house. The caller was fearful that his call was being overheard and put the phone down mid-call

A father said he was worried his daughter would be taken to Gambia to undergo an FGM procedure. The caller told the NSPCC practitioner that some older members of his ex-partner's family had already had FGM and his ex-partner approved of it. The NSPCC practitioner referred the call to children's services

A mother said she was worried she would be unable to protect her daughter from FGM once returned to Nigeria. The caller had FGM done as a child and both her and her husband were against the practice, but her wider family supported FGM and another young family member had recently had the procedure

A member of the public called to share concerns about a young child who was absent from school for a few months in Nigeria. Suspicions arose as the child's mother gave varying explanations for the absence and the child's demeanour was different when she returned, and she would complain about painful toilet trips.

Female genital mutilation

Practised in 29 countries in Africa and some countries in Asia and the Middle East

An estimated three million girls and women worldwide are at risk each year

About 125 million victims estimated to be living with the consequences

It is commonly carried out on young girls, often between infancy and the age of 15

Often motivated by beliefs about what is considered proper sexual behaviour, to prepare a girl or woman for adulthood and marriage and to ensure "pure femininity"

Dangers include severe bleeding, problems urinating, infections, infertility and increased risk of newborn deaths in childbirth

In December 2012, the UN General Assembly approved a resolution calling for all member states to ban the practice

Mr Cameron says, for some, FGM is still shrouded in mystery.

"I don't think people understand in terms of the anatomical details of what is happening to girls - and the trauma behind that," he says. "It is still underplayed."

He likens the reluctance to talk about FGM to the way smacking was silently accepted for years.

"It's not a case of being able to put in a solution straight away and getting a shift overnight," he says. "It's a very complex issue."

Types of FGM

•Clitoridectomy - partial or total removal of the clitoris

•Excision - removal of the clitoris and inner labia (lips), with or without the outer labia

•Infibulation - cutting, removing and sewing up the genitalia

•Any other type of intentional damage to the female genitalia (burning, scraping et cetera)

Comfort Momoh runs the African Well Women's Clinic at Guy's Hospital in London which treats FGM victims.

"The problem is big in the UK," she admits. The clinic sees between 300 and 350 women every year.

The UK problem includes girls being cut here but also being taken overseas - sometimes in school holidays - to be cut before returning home.

Dr Momoh believes numbers are increasing because of migration and because more people are speaking out and seeking help.

She wants to see FGM become part of the core training curriculum for all health professionals to tackle what she says is a complicated problem.

Sexually obedient

Different reasons are given in different cultures for carrying out FGM - including preserving a girl's virginity and keeping her "clean".

It is a kind of child abuse that has been both "normalised" and mythologised in some cultures, says the NSPCC's John Cameron.

Some of the cultural beliefs around it, that women are better cooks if they have been cut - for example - may seem unbelievable but still persist today.

Kanwal Ahluwalia, gender adviser at children's charity Plan UK, is clear what the practice really means.

"It is about gender discrimination," she says. "It is about controlling women and their roles in society."

Victim Jay says reasons vary from initiating girls "into womanhood" to "keeping women obedient sexually".

Many of the women who take their daughters to be cut "don't see anything wrong with it," Kawal Ahluwalia says. "They're doing what they think is right for their children."

And sometimes laws do not hold much weight in rural communities overseas where FGM is committed, she adds, so legal changes alone will not end the practice.

"There is no silver bullet. There has to be a multi-pronged attack. But we have to make sure it is handled delicately to make sure there is no backlash from the community."

Some women choose to be cut, Jay says, seeing as part of staying true to their cultural background.

But she is clear where she stands: "I would never want anybody to go through what I've been through."

FGM and child marriage

130m

have undergone FGM

-

29 countries in Africa and the Middle East practise FGM

-

33% less chance a girl will be cut today than 30 years ago

-

But rising birth rate means more girls in total are affected

-

250m women worldwide were married before age of 15

- Published22 July 2014

- Published22 July 2014

- Published3 July 2014

- Published16 April 2014

- Published6 February 2014

- Published4 November 2013