Syria: Can UK learn from deradicalisation scheme?

- Published

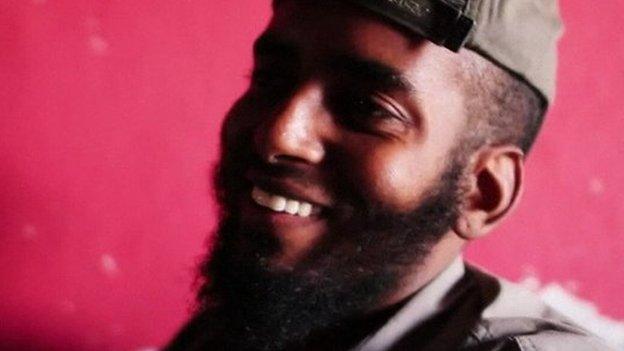

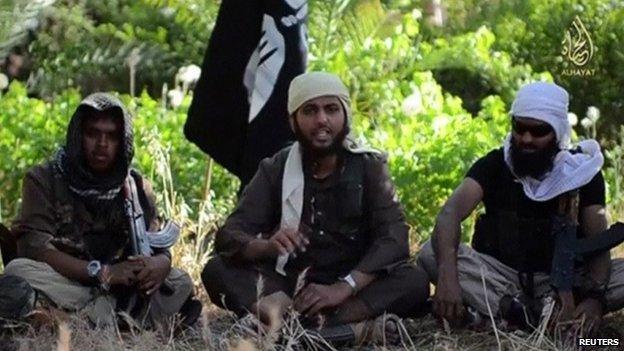

British jihadists appeared in an Islamic State video in June

The Hayat programme in Germany says it has prevented 12 individuals from fighting in Syria. What can the UK learn?

At the Berlin offices of Hayat, family counsellor Daniel Koehler describes a typical phone call.

"You have mothers mostly that call, sometimes extremely in distress. They are crying... they are massively in panic that they might be losing their kids, their children, and never see them again," he says.

In 2012 Hayat - which means "life" in Arabic and Turkish - established a national counselling hotline for families, colleagues and friends who were worried someone they knew was on the path to violent jihadist radicalisation.

The programme provides a bridge between the individual's family and various agencies and bodies, with the aim of helping loved ones to steer the person away from extremism.

Hayat is funded by the German government, but in all other respects is independent.

'Progress'

Syria is now a prime concern. While official figures state 320 Germans have gone to fight in the country, Mr Koehler believes the actual number to be higher.

Since it began in 2011, Hayat has dealt with 100 cases of radicalisation, with significant progress being made in 30 to 40 instances by the counsellor's own estimates.

Indeed, in 12 cases, those concerned were successfully discouraged from participating - or having any further involvement - in the Syrian conflict.

Half of these individuals were already in the country, leading them to return to Germany or move away from the fighting, to Egypt or Turkey.

Hayat counsellor Daniel Koehler stresses the importance of family in the process

Voices of family and friends, explains Mr Koehler, were the deciding factor for many.

"We counted on the fact that there would be feelings of doubt or homesickness. It's at that point the family can provide an alternative view to that of the jihadist group," he says.

'Network of brothers'

The east London youth club in which I meet Hanif Qadir is filled with pool tables and games consoles. The walls are covered with bright graffiti.

It also acts as the headquarters of the Active Change Foundation, a group Mr Qadir set up after his own experience of travelling to Afghanistan in 2002.

"You're meeting people that you think are this network of brothers, that you think are very pious and very humble, but it's quite the opposite. I know many young men have travelled there and thought, 'Whoops, wrong call, quick exit stage left,' but they haven't got that exit," Mr Qadir recalls.

The Active Change Foundation, a non-governmental organisation dealing with issues such as violent extremism in the community, now hopes to bring the Hayat programme to the UK.

'Promising'

Over a cup of tea at her home in north London, Amani Deghayes says the idea looks promising.

"It's the most interesting proposal I've heard so far," she says.

Her 18-year-old nephew, Abdullah Deghayes, was killed in Syria in April.

Two other nephews, Jaffar, 16, and Amer, 20, are still there, with some family members using Facebook conversations in an attempt to challenge their jihadist ideology.

But Ms Deghayes says that any British incarnation must be independent of government.

Currently, she believes the risk of prosecution in the UK could dissuade some individuals from coming home, even if they have had a change of heart.

She says: "You're young, you go there, you might see that the reality is not what you thought - what happens then? You're going to come back [to the UK], you're going to prison, it's almost like you're being trapped in that situation."

The government has warned that those returning from Syria could face prosecution, and has sought increased powers against those who commit terror offences overseas under the Modern Slavery Bill, external currently going through Parliament.

'Shield'

Under the Hayat programme, the aim is for individuals to return to a "safe and controlled positive social environment" where their deradicalisation can continue.

Yet, while Hayat is a non-governmental programme that strives to be independent, moral and legal obligations will often require the police and others to become involved.

Mr Koehler says that by engaging with Hayat, families can make sure this happens in a planned, measured way. The alternative may well be police raids on the family home.

He believes it is important to be transparent with families over the issue, and says many families regard Hayat as a "shield" between themselves and the authorities.

The Hayat programme was established in Germany in 2011

At a recent Home Affairs Committee hearing, the chairman, Keith Vaz MP, asked Home Secretary Theresa May if what he described as the "German model" of favouring deradicalisation programmes over prosecution for those returning was being considered.

The answer was inconclusive. The Home Office was consistently looking to see if there were "other ways of doing things" that have proved successful elsewhere in Europe.

But discussions over how the Active Change Foundation might implement a version of Hayat in the UK are at an advanced stage.

'Become a friend'

Other projects have also sought to involve families in discouraging travel to Syria.

Earlier this year Mrs May helped to launch a video produced by Families Against Stress and Trauma, external, featuring appeals from relatives of those who had gone to fight.

"We're asking families that if they have any concern that their children might be going to Syria, please reach out," its founder Saleha Jaffer told the BBC.

But in some cases, parents are the last to know and Ms Jaffer urges them to take more of an interest in their children's lives.

"If you establish communication with them and become a friend, they might open up," she said.

But Ms Deghayes is doubtful that talking to children alone will suffice.

She recalls how a year before travelling to Syria, one of her nephews wanted to be a male model.

"It's really hard to predict where someone is going to be going at that age," she says.

But that changeability, she believes, opens the door to deradicalisation.

For some young people, extremism is "a way of being in a different group and thinking everyone else is an idiot", she says.

"You can go in and out of such thoughts and ideologies [at that age], and that's hopeful."

PM is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 1700 BST from Monday to Saturday each week.

- Published17 July 2014

- Published11 August 2014

- Published7 August 2014