Z is for Zanzibar

- Published

- comments

Z is a destination, standing enigmatically at the extreme end of the alphabetical line. Crazy zigzags at odds with a gentle song, its qualities are both puzzling and exotic. After Z there is nothing.

Zanzibar, fittingly, enjoys not one but two Zs. It is a word that buzzes with African mystery and rare spices, of foreign adventure and dark magic. For a country looking to attract travellers and tourists, its tantalizing name is perhaps one of its greatest assets.

Blessed with stunning coral beaches lapped by the warm green-turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean, Zanzibar's government is staking the islands' future on being a destination for hundreds of thousands of international tourists. But many local people associate change with turmoil and visitors with exploitation. Transforming Zanzibar's fortunes has not proved easy.

"It is true that we did not start very well," Zanzibar's vice president Seif Sharif Hamad says, leaning across the table as if sharing a confidence. "To be frank with you, there are still some people who are not very happy," he tells me. "They prefer to go back. Some people benefit when there is trouble."

Hamad is no stranger to the strife that has afflicted his beautiful islands over the past few decades. He has done time in Zanzibar's Central Prison on politically motivated charges that served to fuel the acrimony between his Civic United Front (CUF) party and the rival Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM).

Violent clashes following disputed elections in both 2000 and 2005 saw dozens of people killed and hundreds wounded. Thousands temporarily fled the country. But now Hamad believes Zanzibar has turned a corner and a new era beckons.

"Everybody is very safe," he insists. "There is no way someone will come in the middle of the night to knock on people's door. The majority of Zanzibaris are very happy with the situation."

Today Zanzibar looks to be a destination, but for centuries it was a global junction. Its physical position between the Middle East, India and Africa made it a strategic base for traders and explorers. It was at the epicentre of the markets for slaves, ivory and spices.

It remains, though, at a metaphorical crossroads, as it attempts to turn itself from an impoverished East African backwater into a magnet for investors and travellers once again.

"The islands of Zanzibar are based on trade," Hamad reminds me. "We have a lot of resources that have not been exploited yet - seas rich in fish, many very good white beaches which are under-developed."

The archipelago of Zanzibar is part of Tanzania, meaning that it's semi-autonomous. The first holidaymakers arrived in the islands in the mid-80s, but the tourism industry only really began to expand a decade later. In 1995, around 56,000 visitors came to the islands. By 2012 the government was claiming 170,000 had made the journey, with the Zanzibar Commission for Tourism projecting 450,000 will come in 2020.

It is a highly ambitious and challenging target, not helped by the tortuously slow development of the islands' infrastructure. Key to expansion is the building of a new terminal at Zanzibar's main airport, capable of taking direct flights from Europe and beyond. Work began three years ago but then, dramatically and embarrassingly, was forced to stop.

"It was wrongly positioned," admits Zanzibar's Trade Minister, Nassor Mazrui. "They were supposed to build it 93 metres from the centre line of the main runway but they built it 63 metres." Not only had the terminal been built in the wrong place, it was almost a metre too low. As a terminal for larger passenger aircraft, the building did not comply with international aviation standards.

"We had a choice - either demolish and start again, or extend the terminal away from the runway allowing bigger planes to park and with a walkway to the main building," Mazrui explains. They plumped for the latter option and work has now begun again. "By Christmas next year we will have bigger planes coming here," the Trade Minister claims optimistically.

"It can only happen in Zanzibar," hotelier Andrew Smith says with a rueful smile. "Direct flights are critical for the survival of tourism on the islands." Smith was brought up in Kenya where his father ran a hotel business, moving to Zanzibar in the nineties to become one of the pioneers of the islands' expanding tourist trade.

"My hotel was number four or five, with most of the existing hotels catering for Italians who came for all-inclusive holidays with a holiday club," he explains. Smith recalls, though, how Government verbal enthusiasm for such ventures, was not always matched by action.

"There was a dirt track running through our site connecting the coastal villages. We established Blue Bay on the basis the path would be removed, that people would stop using the track and start using a new main road at the front of the hotel," Smith explains.

Local villagers, however, were reluctant to abandon their traditional way, even after months of construction work had been completed. "I told the government we would stop building until they shut the road, hoping to focus minds," says Smith. "It took them 12 months to close it."

The dispute is, perhaps, illustrative of a profound tension for Zanzibar, between the demands of an expanding commercial tourist industry and the lives of ordinary islanders. To some local people, the tourists are like the Indian crows brought to the country by the British: an alien species that threatens the native ecology.

Around 95% of Zanzibar's population is Muslim and some religious leaders have expressed outrage at the sight of Western bikini-clad women or intoxicated men on their streets. Last summer, two British teenagers were victims of an acid attack near Stone Town. Although the young women were soberly dressed and the motive was never proved, speculation has been that the attack was inspired by religious tensions.

Vice President Hamad accepts there are strains. "That can be managed as long as the tourists themselves are respectful, particularly when mixing with the older generation," he tells me. "We want to attract very high profile tourists who are well behaved and not involved in drugs."

"We plan to introduce CCTV in Stone Town and for tourist police to patrol the area," Mazrui says. "From the airport to the hotel we will take care of our visitors."

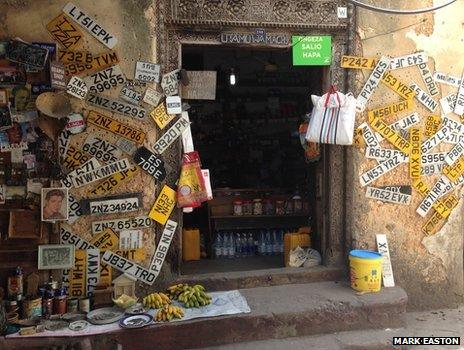

Strolling through the charming historic alleys of Stone Town, there is no hint of hostility. Quite the reverse: the people appear welcoming of and fascinated by European culture. Reaching out to Italian visitors, the largest tourist group by nationality, shops style themselves Manoko Caravaggio or Suleiman Kandinsky. UK and other international car number plates are treated like exotic icons.

England's Premier League is huge in Zanzibar - almost every taxi is adorned with Manchester United, Arsenal or Liverpool colours. On the edge of town, Bad Boy Bob's hairdressing salon is a shrine to Chelsea.

On the beach in front of the hotel, however, the relationship between locals and visitors feels slightly more precarious. Villagers are banned from approaching the foreign guests slowly roasting on their sun loungers. In a country where half the population survives on less than a dollar a day, one can understand the frustration of desperate hawkers trying to entice a few coins from the rich tourists.

"Why don't you want to talk to the real people of Zanzibar?" asks one young man, trying to engage with an English visitor as he straps a huge marlin onto the back of his bicycle.

Throughout history, Zanzibaris have found themselves written upon by outsiders - traders and colonialists stamping their mark on their islands. The site of the slave whipping post and horrific underground slave chambers are firmly on Stone Town's heritage trail, but a reminder too of the exploitation and cruelty that has shaped this place.

For tourism to expand as the government hopes will require the people to be convinced that the arrival of the latest wave of foreigners heralds something truly positive.

"People in Zanzibar know that the tourist industry has improved their lives," Mazrui claims. "The farmers, the fishermen, the taxi drivers, all of them know that the tourist industry has given them a lot of benefits."

The last few years have seen relative political stability in Zanzibar with a government of national unity formed in 2010. The two main parties, CCM and CUF, have worked together in coalition and made tourism a priority for the development of the islands.

"We have a programme now for improving tourism, 10% of our national budget is being devoted to it," Trade Minister Mazrui says. Andrew Smith is optimistic too. "They have got masterplans that they carry around like bibles, and if they stick to their plan I think this will be a fantastic place and a fantastic tourist destination."

Zanzibar's story mirrors the rise and fall of empires and it bears the scars of human greed and hubris. Today, like the letter that begins its evocative name, Zanzibar is looking to become a proudly independent destination.