How serious is the IS threat to the UK?

- Published

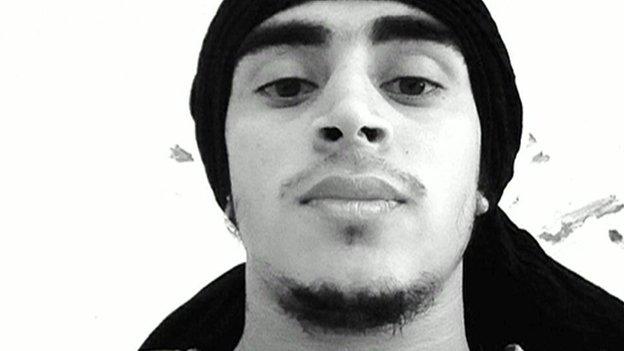

From Wales to Syria: Nasser Muthana (centre) has appeared in an IS video

I've been covering terrorism and security stories for almost a decade for BBC News - and there is one question that's really difficult to answer: How severe is the threat to the UK posed by so-called Islamic State (IS)?

Reporters don't have access to counter-terrorism case files, which is probably just as well, given that our trade relies on us opening our mouths, rather than keeping them shut.

But there is enough information out there - alongside the lessons of history - to provide a good idea of what is going on without resorting to scare stories that will leave people afraid to come out of their homes.

And the short answer is that the current situation is deeply worrying.

It is also, fundamentally, part of a larger terror threat that didn't go away simply because it stopped being front page news.

And, in a twist to the tale, it may be a moment of opportunity to confront violent ideology in a way that it has never been confronted before.

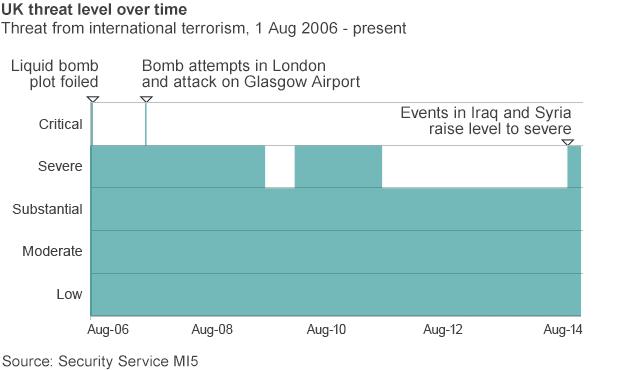

Since August, the official UK threat level, external has been "severe". This means that security and intelligence chiefs have concluded that a terrorism-related attack is highly likely.

In October the mood cranked up a notch again. The Met's commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe said the "drumbeat" around terrorism had become more intense thanks to Syria and Iraq.

Police officers were told to be vigilant because the threat to them had been "heightened".

The news has been full of reports of Syria-related trials - including the extraordinary story of Mashudur Choudary from Portsmouth.

New threat

But the difficulty in assessing the true level of the threat is working out what is new and what is simply a continuation of an existing danger.

In the wake of 9/11, there was a great deal of fear that the Western world would see wave after wave of attempted mass-casualty attacks.

While few of those threats turned into actual attacks, they existed. I and other colleagues across the British media have spent long hours in court listening to detailed evidence, year after year, of serious plots and dangerous men.

Some of the earliest British recruits to violent jihadist/Al-Qaeda ideology were drawn in because of specific grievances: the ringleader of the 7/7 attacks had his first taste of radical political causes when he shook charity buckets for the Kashmir conflict.

And although Al-Qaeda's leadership has been decimated, the jihadi ideology has continued to have a life of its own.

That ideology is a strange brew of utopianism, political anger and religiosity.

And it is now, arguably, reaching a new peak in Syria and Iraq because of three factors well-known to experts who have studied how radical social and political movements develop:

Window of opportunity

Resources and capability

A message to sell to followers

The first European Muslims going to the Syrian conflict were either delivering aid or, to a lesser extent, volunteering to help rebels defend Syrian civilians. Their motivation was comparable to those who went to Bosnia some 20 years ago.

Jihadist flood

As Syria became more chaotic, jihadists seized upon the first of those factors: the window of opportunity. They immediately understood that Syria was the new land of jihad - the new opportunity to build an Islamic State where their predecessors have failed to do so in Pakistan and Somalia.

The second factor, resources and capability, immediately came into play: recruits, weapons, experienced fighters and functioning organisations capable of taking military or political control of some of its targets.

One of the earliest British recruits - Iftekar Jaman from Portsmouth - tweeted and blogged how the Syrian warzone was some kind of land of milk and honey. He's now thought to be dead - but not before his message enticed others to follow him.

This is where the third factor - a compelling message or narrative - has played an instrumental role.

Jaman's successors (those who aren't dead) seem to be more motivated by the temptation of living in a surreal fantasy land of fighting, rather than building a peaceful state.

Ifthekar Jaman, who's in Syria, has been speaking to 'Newsnight' reporter Richard Watson

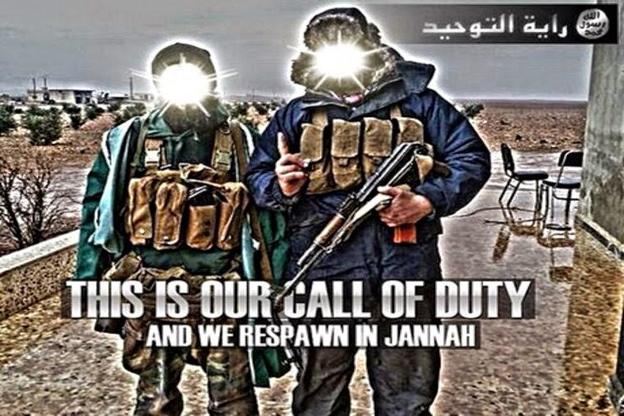

More than one Muslim involved in de-radicalisation has described this to me as the "Call of Duty" mentality - a reference to the popular video game.

What's their call of duty? To the "Islamic state" - a caliphate of a conquering army. These recruits are overwhelmed by the belief in this state as something that all Muslims should aspire to and the sword is their only route to its creation.

They seem to include men like Nasser Muthana from Cardiff. He appeared in an IS recruitment video, posted pictures online of crude bombs he claimed to have made and, possibly, appears in an stomach-turning video in which Syrian soldiers are killed.

What's more, many of these recruits seem to believe that Syria - or more precisely the IS-held town of Dabiq - is at the heart of an apocalyptic prophecy in which Muslims and their enemies will meet one final time.

Liberating people from an evil dictator? That's not really on the agenda anymore when you have a group trying to goad its global enemies into an end-of-the-world confrontation.

And its amid this chaos and carnage that the real security issue for the UK reveals itself.

Deeply motivated

Security chiefs believe that the recruitment pipeline to Syria's many factions has been narrowed.

But that means that those who are making it out there are singularly motivated by IS's message to join the fighting or, in the case of women, to support the men who do.

Not all of them will get their wish to die a martyr's death on a battlefield.

IS uses imagery from games such as "Call of Duty" in their recruitment

If they don't come back, then they will continue to use the internet and social media to propagate a worldview that is carefully packaged to appeal to Western audiences.

They have created direct connections to would-be recruits in a way that has been seen in no previous conflict.

Some of them will come back - and a smaller number of them will have a very clear idea of who IS thinks the enemy is - and their role in attacking that enemy. This is what security services call "blowback".

Secondly, IS knows it cannot draw in everyone that it would wish - so its leaders want to radicalise those who can't make the journey.

It urges them to see Muslims as victims of the West - with one of its clerics having issued a fatwa calling on followers in the West to launch attacks at home.

So what kind of threat will they pose?

The last few years has shown that, by and large, the British security and intelligence agencies have become adept at disrupting large plots that take months to plan.

Today, security chiefs are just as likely to be concerned that there will be another attack similar to the killing of Lee Rigby in Woolwich - one or two individuals, no warning, no chatter.

Self-destruction

This all sounds like utterly appalling bad news. But, here's the twist.

There is credible evidence to suggest that the IS group could ultimately begin to destroy itself.

The Soufan Group, an influential American security organisation, argues that the IS video released to mark the murder of Peter Kassig shows the group at "its most desperate and least triumphant", external.

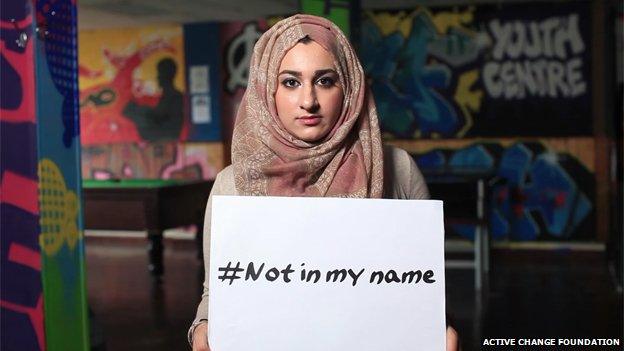

The shocking events are also spurring Muslims across the West to challenge the extremist narrative.

The toxicity of IS's creed is far removed from the gentle piety and community-building that forms the heart of your average Muslim community. Unlike previous threats, this one is unavoidable. And while there have been many British Muslims who have spent years quietly challenging extremism - the noise from IS is forcing them to be more vocal.

There is still a huge gulf of trust between many Muslim communities and the UK government - not least because of accusations that the British don't want to challenge Israel over Gaza.

But nobody is in any doubt anymore that there is a real threat from IS and somehow it has to be stopped.

- Published20 May 2014

- Published26 October 2014

- Published9 October 2014