Thwarting terror's cyber warfare

- Published

Islamic State has made skilful use of social media

The report into the killing of Lee Rigby has drawn attention once more to the battles over terrorism in the online world.

It raised questions over whether social media sites should be doing more not just to take down extremist content but report it to the authorities.

Policing the internet - or spying on it - is becoming one of the most fiercely contested policy issues in Britain and the US - one in which companies and states clash, as well as those groups espousing violence, clash.

In Scotland Yard, a small team of a dozen or so are working on the front lines of modern counter-terrorism. Their battleground is social media.

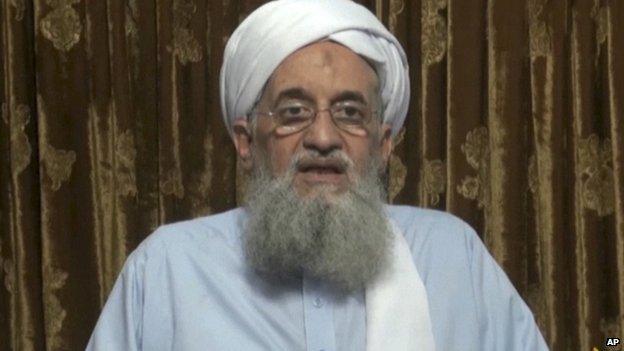

Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of al-Qaeda, once claimed that "more than half the war is taking place on the battlefield of the media".

Today that means online. Old-school al-Qaeda is not the one fighting it though. The group calling itself Islamic State (IS) is instead at the forefront.

IS has proved adept at using the latest technology to reach out across the world.

Slickly produced

A new generation of young jihadist recruits are comfortable with social media often in a way that the old al-Qaeda was not.

They have used the internet and Twitter to distribute slickly produced videos which are designed to intimidate, but also recruit to the IS cause.

The imagery of beheading videos is similar to those seen a decade ago in Iraq.

What is different is their reach. Social media means they can go round the world in minutes and be hard to remove from the web.

'It is very graphic and because of the internet it can reach people's homes, their bedrooms, their phones very quickly," says Ch Supt Clarke Jarrett, who runs Scotland Yard's Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU).

"And we are very concerned about young people viewing this material and the impact it will have on them."

Young are target

He believes much of the content is tailored specifically to the young.

The CTIRU team at Scotland Yard scour the internet to find any material that glorifies or encourages terrorism and watch the individual accounts that jihadist media teams use to propagate their messages.

The content they are after ranges from bomb-making instructions to videos of beheadings.

Ayman al-Zawahiri highlighted the importance of the media

That definition is vital because when they spot something they then approach the Crown Prosecution Service to confirm that the material breaches UK law prohibiting the encouragement or glorification of terrorism.

With that in hand, they then approach social media companies to ask them to take the material down.

Since February 2010, the unit has taken down more than 49,000 pieces of content, more than 30,000 in the last year.

The more gruesome videos are certainly harder to find but not impossible.

Often, they go off the mainstream sites within minutes of being posted but can still be found with a bit more work. It is a cat-and-mouse game.

Most of the social media companies are not headquartered or based in the UK and so the process is voluntary and depends on those relationships.

How effective is the system?

"That depends on which company we are working with and the relationship we have," says Clarke Jarrett.

The Home Office is working to build relationships with more companies, especially smaller and newer providers, although they are reluctant to single any out by name who are not doing enough.

Rising tension

The way in which social media has become the new battleground means tensions are rising.

The head of GCHQ launched a broadside on social media companies on his first day in office describing them as having "become the command-and-control networks of choice for terrorists and criminals".

Robert Hannigan accused firms of being "in denial" about the way in which the internet was being used and called for "a new deal between democratic governments and the technology companies in the area of protecting our citizens".

That was privately met with incredulity by some large technology companies (both British and American) who felt they were already co-operating extensively with the government in areas like the CTIRU.

New proposals announced by the prime minister while in Australia to increase filtering and reporting of extremist content were also met with some bemusement by communications providers who would only say they were in discussion with government.

A team at New Scotland Yard monitors posts

What is clear is that as well as a battle online with the jihadists there is a battle over public opinion.

Many technology companies were badly bruised by the Edward Snowden revelations which showed how they worked with intelligence agencies (under compulsion of law, they maintained).

That exposure led some of them to distance themselves and also to push more privacy-focused systems using encryption.

The state is now worrying that this trend may damage their ability to get into their targets' communications and so they are pushing back in public statements and trying to corner the companies into doing more, knowing that legislation is not always an easy option when you are looking at a global internet.

Recent emergency legislation tried to ensure that companies will comply with warrants to deliver up content they hold even if the company is outside the UK.

The ISC report into Lee Rigby led to talk from the Prime Minister of the need for more "social responsibility" from companies.

The government seems to want them to not just take down content on demand and close accounts automatically but also pro-actively inform law enforcement if they see content which might relate to terrorism (as it is said they do for child abuse).

But the companies are nervous of being seen to spy on their own users on behalf of governments.

They also question what happens when other countries - say authoritarian regimes - ask for them to provide information on users who are breaking their laws which might define terrorism in different ways.

Tensions over free speech and preventing radicalisation; over national laws and international companies; over privacy and security are all colliding in the digital space and in the world of social media.

This battle will only grow more intense.

- Published9 October 2014

- Published27 January 2014