Potent and provocative symbol of the flag

- Published

The Confederate flag is loaded with potential meanings

Flags are intentional symbols, weaved to wave proudly and to rally the troops, in victory or defeat.

"Here we make our stand, come and join us," they declare.

But flags are slippery things, like bars of soap sliding from hand to hand, changing meaning the whole time.

There's no text to tell you what they are saying, it is all about how you read them, or misread them.

St George's flag here and the Southern Cross, external in the US shout about pride in a culture sometimes scorned by a metropolitan elite.

Battle flags can be recaptured, hoisted aloft with new resonance, but the shadow of history flutters behind them.

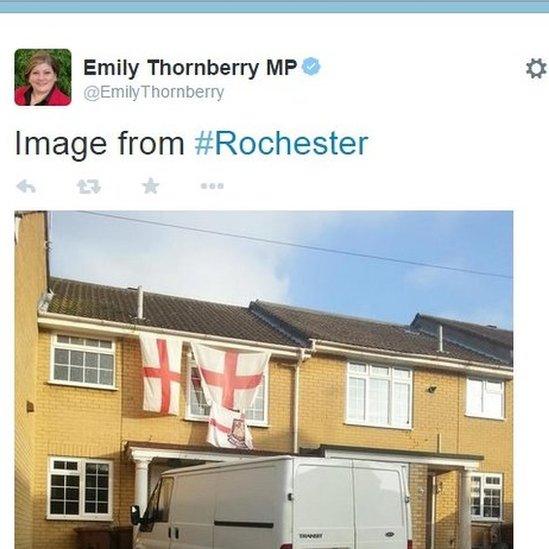

Of course, these reflections go back to that unwise tweet, external from the then shadow attorney general.

I wish Emily Thornberry could have been with me on my recent visit to Great Yarmouth.

I bought my morning newspapers from a shop along the front. Outside, a small England flag sat atop a wire basket full of footballs.

Inside, cigarette lighters were on sale - for some people still smoke - the red cross on a white background.

Unsympathetic message

In my journey into town I passed the Tudor Tavern, a whitewashed pub, a bold red cross on front and side.

The pink and blue pastel of the children's merry-go-round by the indoor market was topped by no less that 10 St George's flags flapping gaily in the drizzle.

It is the ubiquity of this symbol that turned Emily Thornberry's tweet into a symbol all of its own - of a party, unsympathetic and out of touch.

She made her daytrip to Kent seem like an academic anthropologist venturing daintily out into the field for the very first time. No grass skirts - but oh those flags!

Those with a political motive were happy to impose their own meaning.

The bovver boys of the red tops gather round to put a boot into Labour, eager to declare the party has broken its connection with its old power base, the working class.

But they have perhaps shown a wilful blindness to what the flag has meant.

The artist Tom Hunter brilliantly records the lives of "ordinary" people in his photographs - around Hackney, in squats and the shops, restoring dignity and colour to those who are often overlooked, external.

He told me (incidentally wearing a T shirt with a red, white and blue roundel - mod symbol or RAF identification?): "That flag means different things at different times to different people.

"A few years ago I used to sell stuff on Brick Lane Market and the National Front used to patrol there, and the English flag was used as a badge of honour, as if to say, 'We are something, and the Bangladeshi and Pakistani community there were something else', and that was pretty abhorrent - nasty people spouting nasty dogma."

Class raw nerve

But what Emily Thornberry has missed is that the flag has been reclaimed.

The tweet was posted on polling day in Rochester

"In the last few years, through football mainly, the English flag has become something quite different," said Hunter.

"It has become celebratory. When England are playing, I am very glad to see that English flag."

While the flag's past may make some queasy, Islington Emily also touched a raw class nerve.

The middle class sneering at vulgar working class display, whether flags on a house, homes covered top to bottom in Christmas lights, reindeers and Santas, floral tributes saying: "Goodbye Mum," or gaudy knickknacks is nothing new.

The outraged commentators probably don't deck their own homes with flags.

The Labour Party is hardly immune to such prejudice and indeed can argue some ideological underpinning for it's snobbishness - a sort of false consciousness of the Christmas lights.

The party has been full of bourgeois intellectuals who celebrate the working class at arms length but can't abide "trade".

One can't imagine New Statesman founder Sidney Webb enjoying a pint of mild and bitter in the public bar, playing shove ha'penny to pass the time.

But this little tiff, largely conducted in the media, is just a pale reflection of the culture wars fought daily in the US.

There white van man (and he is white), drives a jacked-up pickup with big lights, mud-grips, and he is "country to the core".

A good proportion of country music isn't about love or romance but about being rudely proud of your down-home, rural roots, in the face of presumed metropolitan distain.

It celebrates robust, rough rural reality, from bare feet and a six gun on the dash (board), to mending things with duct tape, and dogs running wild in the yard.

And, as the song, external goes: "If you don't like that, you can kiss my country ass."

This isn't old guys on the porch moaning about days gone by - it is the Jawga Boyz (say it out loud) and the Lacs combining country and hip hop to proclaim the same defiant message.

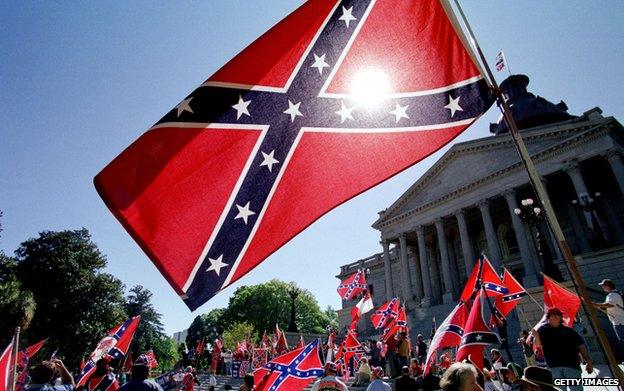

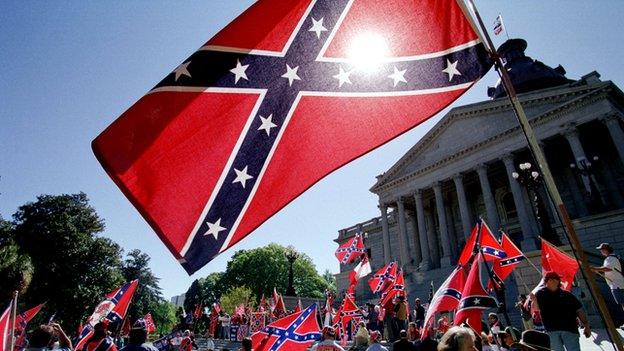

Some of these people also have a flag - the Southern Cross, the battle flag of the Confederacy.

It is not as common as it once was, and it has been banned from most official buildings.

But it is still a part of some state flags and it is everywhere - on the side of houses, on T-shirts, on licence plates, and flying from flagpoles in front gardens.

People may argue that it is just another part of heritage and history, pride in the southern states, and it is only Yankees who find it offensive.

Some who say that may actually believe that.

Celebrating rebellion

But many more know it is more than a sly celebration of treasonous rebellion.

It tells every black person within range that you are on the side of those who wanted to keep them as slaves.

And more than that.

For it hasn't been a constant regional symbol since the defeat of the Confederacy - its resurgence, external was a protest against the civil rights movement and desegregation in the 50s and 60s.

There are many things to love in the southern celebration of the everyday, but this flag isn't one of them.

Thinking fondly of my holidays in the south while thinking about this article, I was watching a music video I rather enjoy, featuring big guys dancing and flipping burgers and boisterously splashing giant quad bikes through mud holes.

There was just a brief flash of a flag, less than a second. I'd always missed it before.

Freeze it and you'll see Old Glory, with a Smiley face superimposed and the legend: "If this flag offends, you've made my day."

You really don't have to guess its meaning, in this case the text is part of the flag.

Maybe they are talking about snooty northerners who don't like cookouts and mud. But I doubt it.

The Southern Cross has not been recaptured by the whole nation.

Some symbols can be fixed in time by atrocity and may only get unstuck by generosity, and irony.

It is hard to imagine the Hindu good luck symbol, external ever being prised from Hitler's semiotic clutches.

The English flag may have had its origin in the crusades, but its relatively innocent and ancient origins mean it was perhaps not so hard to seize the standard back.

But there should be no place to hide behind the flag.

- Published30 August 2013

- Published21 November 2014