UK migration: What's really happening?

- Published

- comments

The prime minister's speech on immigration is being billed as a plan that will change the face of the nation - but the official figures published yesterday show how it has already been transformed - and will continue to change in an era of mass movement of people.

The Office for National Statistics is charged with providing its best estimate of what is going on, based on a number of different measures, all of which have limitations,, external.

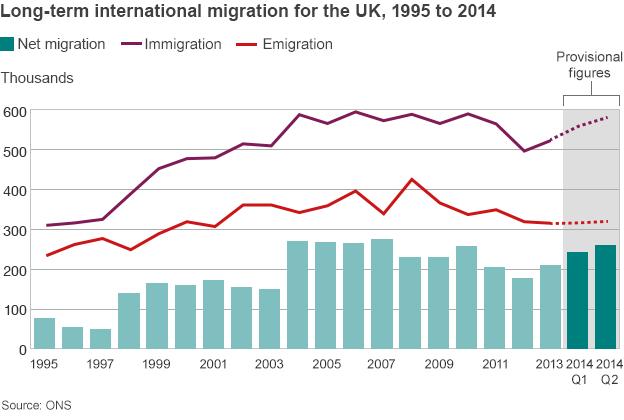

Its November 2014 ONS stats suggest that 583,000 people came to live and work in the UK in the year to June 2014. That includes an increase of 45,000 people from the EU and 30,000 from the rest of the world.

Separate figures for emigration suggest that around 325,000 left the UK over the same period. Both of those movements includes a portion of British citizens exercising their right to come and go.

The difference between these two is called net migration and this gives us an idea about population growth.

Note: 2014 shows provisional rolling quarterly estimates

In the year to June 2014, net migration was 260,000 - and that was well above the Conservative target of getting it down to tens of thousands by the 2015 general election.

For 20 years, the UK has seen more immigration than emigration - reaching a peak in 2005. Net migration began to drop in the wake of the credit crunch economic crisis and then again from 2011 after the government restricted entry for some people from outside of Europe. But now net migration is on the rise again.

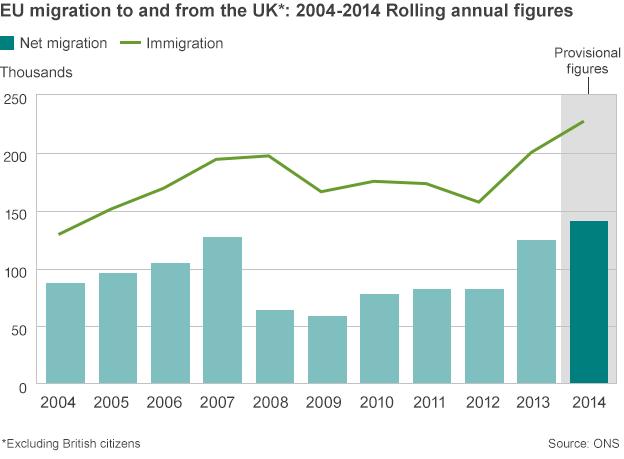

The government has suggested that much of the increase in immigration is due to EU citizens coming to live and work in the UK. It points to the fact that 142,000 more EU migrants had entered the UK over the previous 12 months than left.

All the data shows that this is indeed true - for the past decade there has been an enormous rise in the arrival of EU citizens to the UK. These movements were initially triggered by the then Labour government's decision to allow Eastern European workers access to the British labour market while other EU members kept temporary restrictions in place.

But since the Eurozone crisis has left many parts of the EU in the economic doldrums, the UK has also started to see new movements from western Europe.

Non-EU immigration grows

So is the government right to point the finger at its lack of controls over EU migration?

Only to a point, say most experts, such as Oxford University's Migration Observatory, external.

Even if immigration from the EU had stayed level, or fallen slightly, net migration to the UK would still have risen.

That's because the number of people coming to live and work in the UK from the rest of the world not only exceeds those from the EU but it also increased in the last year.

After three years of falling numbers, in the 12 months to June there was net migration of 168,000 from the rest of the world, an increase of 20% on the previous period.

In the same period there was a 10% increase in work-related visas granted to people from outside the European economic area - the majority of whom were skilled workers.

So policies to curtail immigration from outside of Europe have not only failed to deliver the cuts that ministers hoped they would, the direction of travel has now reversed.

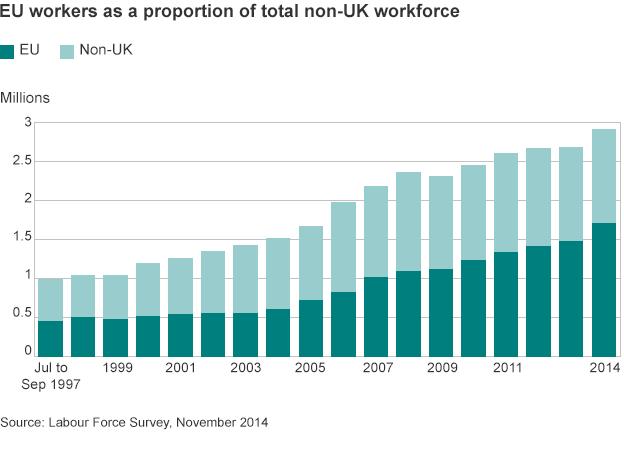

But not only do EU migrants form a smaller proportion of those coming to the UK, they may also be more productive when they get here.

Most migrants coming to the UK are looking for work, but those entering from the EU account for more than half of all the workers in the UK who are not British citizens.

National Insurance numbers issued to EU citizens increased 6% to 421,000 in the 12 months to June, with the largest number - 92,000 - allocated to Polish citizens.

Latest figures for the third quarter of 2014 show there were 1.7m EU workers in the UK, out of a total non-UK national workforce of 2.9m.

David Cameron is expected to propose major cuts to in-work benefits and tax credits to new migrants in an attempt to reduce the numbers coming to the UK.

But it remains completely unclear what effect this would have given that many of these workers are from low-income economies.

Think tank Open Europe says EU migrants are slightly more likely to claim in-work benefits than UK nationals. It says EU migrants make up 5.56% of the UK workforce, but families with at least one EU migrant make up 7.7% of in-work tax credit claims.

But another report produced by University College London found that immigrants from the 10 countries that joined the EU in 2004 had contributed more to the UK than they took out in benefits.