End scandal of mentally ill being held in police cells, MPs say

- Published

Last year 236 children were detained in a police cell under section 136 of the Mental Health Act

The number of people with mental health illnesses being detained in police cells is a "scandal", MPs have said.

A Home Affairs Committee report called for a change in the law, external so that police cells were no longer deemed a "place of safety" under the Mental Health Act.

About 6,000 adults and 200 children with mental health issues were detained in police cells last year because of a shortage of space in NHS hospitals.

Home Secretary Theresa May said the government was reducing the numbers.

'Clear failure'

Currently, people detained under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 can be held in a hospital or police station for up to 72 hours.

Police have been forced to "fill the gap" because of a lack of NHS facilities, the chairman of the cross-party committee, Labour's Keith Vaz, said.

He called for the detention of children with mental health issues in police cells to "cease immediately".

Last year 236 children were detained in a police cell under the law.

"These people are not criminals, they are ill and often are experiencing a great deal of trauma," he said.

He said in many cases detentions acted as the "starting point" for those who were mentally ill to enter the criminal justice system - often ending in prison.

Analysis

BBC home affairs correspondent, Danny Shaw

Finally, it seems, there's a will to change.

For years police have complained that too much of their time was spent dealing with people who needed specialist mental health care.

Now, a consensus is forming that a noisy, brightly lit police custody suite, with drunken hooligans and gangsters sometimes passing through, is simply not an appropriate place for someone in the midst of a breakdown.

The question is: can adequate alternative accommodation to police cells be found - and funded - at a time when the NHS is so stretched?

Ensuring support is available after detention under the Mental Health Act is also crucially important.

What is striking is that while deaths in custody have declined over the past six years, apparent suicides within two days of release have increased.

Care does not, and must not, stop at the gates of the police station.

The committee's policing and mental health report also found:

"Too many" NHS clinical commissioning groups are failing in their duty to provide enough hospital "places of safety" that are available 24 hours a day

There is a "clear failure" of NHS clinical commissioning groups to provide for children with mental-health issues. The NHS needs to make places available locally, it said

Taking people experiencing a mental health crisis to hospital in a police car was "shameful and in many cases added to the distress" and an ambulance should be used

The police need to make sure they use their powers in relation to mental health correctly, to reduce the numbers detained

NHS clinical commissioning groups need to acknowledge the level of demand for mental health facilities

'Do more'

Mrs May said she had "always been clear that people experiencing a mental health crisis should receive care and support rather than being held in a police cell".

She said reforms were "already bearing fruit", with 22% fewer people held in cells under the Mental Health Act in 2013/14 than in the previous 12 months.

But the Police Federation of England and Wales said ministers must "do more" to ensure mental health patients were treated by the NHS "instead of leaving it to police officers".

Doug Campbell, mental health lead for the federation, said: "Just as you would not expect a doctor to run a complex police investigation, police officers can never be an adequate replacement for medical staff."

'Heartbreaking'

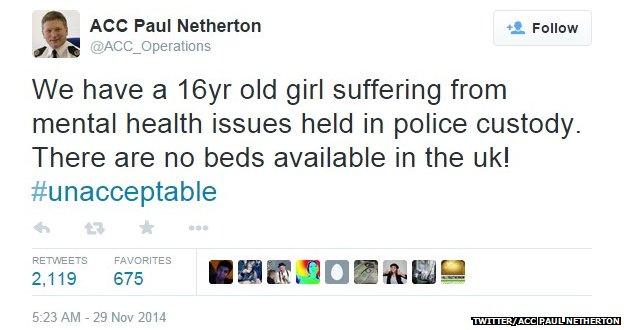

The report comes after a mentally ill teenager was held in a cell for two days last year due to a lack of hospital beds.

Her mother said the 16-year-old girl had suffered "heartbreaking" failings in her care.

NHS England later apologised and described her care as "unacceptable".

Paul Netherton, Assistant Chief Constable at Devon and Cornwall Police, took to Twitter to express his frustration at the police having to detain a teenager with a mental health illness

The case sparked an outcry and debates in Parliament, leading to Home Secretary Theresa May announcing an overhaul of mental health laws in England and Wales.

Care minister Norman Lamb, who has spoken out about the issue in the past, said real progress had already been made, and added that "in many parts of the country it's now a thing of the past".

Local authorities in England have pledged to ban the practice.

- Published18 January 2015

- Published18 December 2014

- Published25 January 2015

- Published18 January 2015